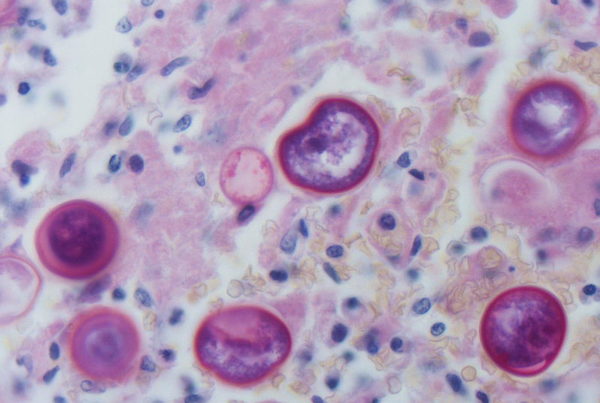

Raising cattle anywhere is hard, but it’s especially hard in the Rio Grande Valley. And that’s thanks to fever ticks. They can spread a fatal disease that decimated cattle herds through the 1900s and is still feared today. And it’s not just the ticks themselves that can cause headaches, but the regulations designed to control them.

Ranchers from counties along the Texas border exist in what’s called the fever tick quarantine zone. It’s a buffer between Mexico, where the ticks come from, and the rest of Texas. If left unchecked, fever ticks have the potential to cause billions of dollars in damages to the cattle industry. So any time a rancher under quarantine wants to move his cattle outside the quarantine zone, they’ve got to treated for ticks. And that’s a burden.

Matthew Rodriguez works with ranchers in Willacy County as a Texas A&M Agrilife Extension agent

“It’s a lot of money for these ranchers to move cattle, to get them sprayed or dipped, whatever the case may be,” Rodriguez says.

Treating for fever ticks requires either a dip vat, where cattle swim through insecticide, or a spray box. Cattle step into a box, the box closes, they get sprayed with tick-killing chemicals, the box reopens and the cow gets out. Both methods achieve the same goal, but there’s a big difference between them: spray boxes are portable, dip vats are not. So as you might imagine, lots of ranchers prefer the spray boxes because they’re more convenient. Or at least, they were more convenient until last week, when Texas Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller banned them.

“I went with my inspectors down to actually myself, to Raymondville to inspect one of these boxes in the progress of spraying cattle,” he said.

Miller said he learned of complaints about the spray boxes back in May – that cattle were getting sick and even dying after going in them. When he went to check them out for himself, he didn’t like what he found.

“They are basically gas chambers,” he said.

The spray boxes are operated by the Texas Animal Health Commission or TAHC, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, USDA-APHIS. Miller says the problem is how the chemical is being sprayed. It’s a product from Bayer called Co-Ral, and it’s the only insecticide approved for use in a spray box that will also kill fever ticks. Miller and the TAHC disagree on a line on the Co-Ral label.

“The label specifically says ‘do not use in non-ventilated area.’” he said.

And in his opinion, that applies to both the livestock being sprayed and the human doing the spraying.

But according to the TAHC, “our interpretation of that and our understanding of that is that part of the label applies to the operator, to the person actually doing the spraying. It’s not directly related to the cattle or the animal being sprayed,” said Dr. Andy Schwartz, the TAHC executive director, speaking at a commission meeting on Tuesday.

And the label’s interpretation isn’t the only point of disagreement. Miller says he has affidavits from ranchers swearing their cattle died after being treated in a spray box. But others say there’s no evidence of that happening. Kaleb McLaurin is the director of government affairs at the Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association.

“No cattle to date have ever been tied to dying due to toxicity from going through a spray box,” McLaurin says.

TAHC Director Schwartz said that while cattle may occasionally have a bad reaction to a spray box, he’s never seen a credible, documented case of an animal dying in the 40 years that spray boxes have been used in south Texas. According to Danny Davis, that’s “just plain bull[bleep], in my opinion.”

Davis ranches in Cameron County, where he owns about 300 head of cattle. He’s part of a lawsuit with other ranchers from the Valley who are suing the USDA and the Environmental Protection Agency for damages, claiming the use of Co-Ral in spray boxes killed their cattle.

“Well I’ve lost probably total between, about 20 head,” Davis says.

The defendants deny that any cattle deaths are related to the spray boxes. A judge is currently considering their request to dismiss the case. If Co-Ral caused those deaths though, it would have happened quicker than most ranchers report, according to Don Thomas.

“It’s like drinking tequila,” Thomas says. “If you drink a bottle of tequila you’re going to get drunk today. If you’re going to get poisoned it’s going to show up within a few hours. Within 24 hours certainly your animal’s going to get v sick or die. It’s not going to happen a week later. And those are the stories we’ve heard.”

Thomas is a fever tick researcher USDA-APHIS. He and his colleagues, as well as the Texas Animal Health Commission hopes that Commissioner Miller reverses his decision and lets ranchers use the spray boxes again. For that to happen, Miller wants the boxes to have improved ventilation – like giving the cow room to poke its head out of the box. He’d also like the agencies to exempt more vulnerable cattle from spraying, like calves and older, weaker animals. Miller said that if the agencies agree to those terms, he’d allow the spray boxes to reopen for 45 days while a more permanent solution is discussed. He and the TAHC were supposed to meet earlier this week, but according to Miller, the meeting never happened.

In response to Miller’s claim that they missed the meeting, the TAHC sent out a statement that said “TAHC has always worked to protect the health and marketability of Texas livestock and poultry and we will continue to work with our federal, state, and industry partners.” In the meantime, the health commission is working to get official clarification on the Co-Ral label.

At a recent TAHC meeting, one commissioner asked executive director Schwartz whether they should ask a court for an injunction to operate the spray boxes while negotiating their proper use. Schwartz said that while that wasn’t his preference, they’re not taking any options off the table.