From Marfa Public Radio:

These days, there’s not a whole lot going on in Ruidosa. By most estimates, the town is home to about 15 people. But it used to be one of the more substantial settlements in the Big Bend region, and now a local group is working to restore one of the last monuments to that past era before it crumbles back into the earth.

You wouldn’t know it by driving through Ruidosa today, but back in the 1930s and 40s this stretch of the Rio Grande was home to a substantial cross-border community of farmers and ranchers.

That’s the Ruidosa that Chon Prieto remembers.

“There [were] a lot of people in Ruidosa at that time,” Prieto said, sitting in the yard outside his house in Presidio on a recent afternoon. “Ruidosa, Candelaria, across the river, Barranco de Guadeloupe.”

Prieto, now 82 years old, lived in Ruidosa until he was nine, when there were several hundred people in the area, many of them growing cotton. Prieto remembers at harvest time his grandfather giving him an empty sack and sending him into the fields.

“And I would fill it up and he would give me ten cents. It was quite good money for that time,” he said with a laugh.

Chon Prieto at his home in Presidio. Prieto has fond memories of growing up in Ruidosa and attending church there.

Ari Snider/Marfa Public Radio

At the center of town was a big two-story adobe church, raised from the mud of the Rio Grande by local workers in the early 1900s. On Sundays during his childhood, Prieto would walk into town to attend mass there, picking up some flowers along the way to leave at the church, as was customary.

“I loved going to church,” he said.

Part of the draw was the fun that awaited him after church — visiting with his grandmother, who owned a grocery store right across the street, and let him pick out whichever candy he wanted from the shelves.

“What do you want, Chonté?” Prieto remembers his grandmother asking, using his nickname.

“‘Oh I’m gonna take some Mounds.’ You remember those candies? They still exist!”

In those days, the town had a handful of stores, and the adobe church was in a fine state, boasting a front door with decorative glass panes, hardwood flooring, and a big church bell mounted on the roof. In historical photographs, it looks like one of the largest buildings around — both the product and a symbol of an active community.

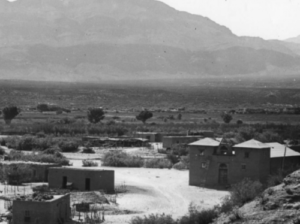

The town of Ruidosa, looking across the Rio Grande into Mexico, ca. 1918. At that time the region was home to several hundred people, many of them cotton farmers.

Photo courtesy of Friends of the Ruidosa Church

But those times didn’t last — a combination of drought, increased upstream irrigation, and a massive dam in New Mexico severely reduced river levels in the mid 1900s.

“So that farming community, it literally evaporated,” said Mike Green, a retired architect with Friends of the Ruidosa Church, a local group working to give the building a second life as a community space.

As the town dried up, the church was left abandoned.

“The church couldn’t really justify maintaining the structure,” Green continued. “So now it’s on us to do it.”

And, they’ve got a lot of work to do. I visited Ruidosa on a recent evening, to see the church firsthand.

The hardwood floors are long gone, and the slumping window frames are shored up with wooden braces.

The adobe structure bears the scars of decades of neglect, and restoring it promises to be a years-long endeavor.

Charlie Angell is active in the restoration effort and gave me a tour of the church’s cavernous interior.

“And everything you see here is what has just melted away through the years,” he said, gesturing at a pile of dried mud on the floor. “This is a couple feet of adobe plaster that has just weathered off and washed off.”

Despite the wear and tear, it’s still imposing structure, the eroded bricks and two squat towers giving it the air of an aging fortress.

“I dunno it kinda stops you in your tracks,” said Clara Bensen, also with Friends of the Ruidosa Church.

One of Bensen’s roles in the restoration project is to collect stories from people who knew the church when it was still operational.

People like Chon Prieto, who rolled up in his white pickup truck while we were at the church. He still runs a small ranch upriver, and drives through town a couple times a week — past the site where his grandmother’s store once stood, past the old church where he used to leave flowers on Sundays.

“Well it makes me very happy. It makes me happy,” he said, adding that he always remembers to cross himself whenever he drives past the church.

Chon Prieto leaving Ruidosa after stopping by the church.

Carlos Morales/Marfa Public Radio

Addressing the members of the restoration group, Prieto expressed his thanks. “And I’m very grateful to you all for trying to do something about it,” he said.

Tonight, though, he doesn’t have too much time to reminisce — he’s in a bit of a hurry to get back home after a long day at the ranch.

So he fires up the old ranch truck, and heads off downriver.