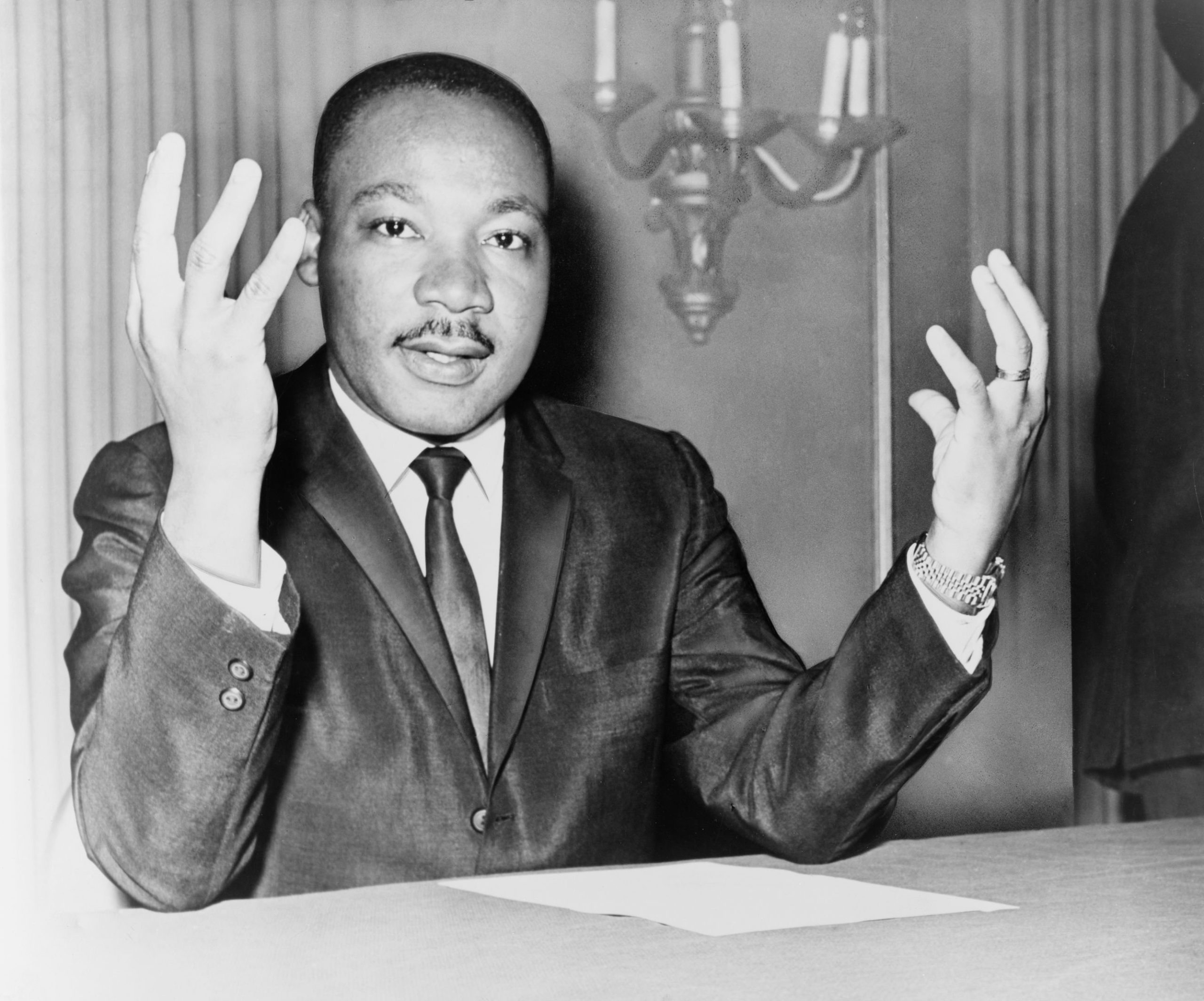

Had he lived, Martin Luther King Jr. would be 94 years old this year. The tragic brevity of his life, cut short by an assassin in 1968, remains a testament to the enduring impact he had during his short time on Earth.

Although some find it hard to believe, King lived in a political climate and historical era not so different from our own. Civil rights activists were pilloried as anti-American subversives, communist dupes and an unpatriotic mob – rhetoric echoed in contemporary attacks against Black Lives Matter protesters and even school teachers whose classroom explorations of Black and American history have triggered a political backlash reminiscent of the civil rights era.

Then, as now, racism, war, poverty and violence scarred the domestic landscape, and its parallel growth in the international arena threatened world peace and stability. Social justice movements swelled at home and abroad, and anti-democratic forces organized strongholds in America that, although rooted in the Deep South’s former Confederacy, stretch from sea to shining sea. At the same time, the search for what King called the “Beloved Community” – a world free of war’s pestilence, racism’s violence, and poverty’s indignity – inspired social justice and peace activists in King’s time, just as ours.

In our own time, contemporary activists advocate for the abolition of racially biased systems of punishment, incarceration and policing. And as their forerunners did, they continue to press for voting rights, equal education and environmental justice in communities of color – all a continuation of King’s legacy. “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” King observed amidst the tumult of 1963 in his letter from Birmingham Jail. “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.”

King blasted his era’s version of white allies, confessing to being gravely disappointed with the white moderate. King challenged the moral equivalency of his day, which found white political and civic leaders at times castigating both the practitioners of Jim Crow segregation and the civil rights activists who also protested against this unjust system. This kind of political handwringing is reflected in parts of today’s political climate, where white moderates hesitate to support voting rights, often misinterpret prison abolitionists as anti-police agitators, and have failed to make a robust case for protecting the rights of educators to teach the fuller story about American history to schoolchildren.

King wrote in 1963, “I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s greatest stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizens Councillor or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate who is more devoted to order than to justice; who prefers a negative peace, which is the absence of tension, to a positive peace, which is the presence of justice; who constantly says, ‘I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I can’t agree with your methods of direct action.'” Only months later, King explained at the March on Washington, “Now is the time to make real the promise of democracy.”

MLK Day 2023 reminds us that the partisan divisions of today are not so different from the political landscape faced by King in his time. The passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act were not preordained, nor were they universally beloved pieces of legislation. They were controversial and hotly debated and punctuated a decade of uprisings that conservatives decried as riots, activists regarded as revolts, and the government characterized as civil disturbances.

King famously characterized riots as “the language of the unheard.” Less well known is his sharp criticism against political moderation from his Birmingham jail cell. Dr. King might find, in our current age of assaults against teaching Black history of voter suppression and backlash against struggles for racial and economic justice, a depressingly familiar reminder of the challenges he faced 60 years ago. However, King remained defiantly optimistic in the movement’s ability to bend history’s will toward a long-delayed recognition of Black citizenship and dignity. “We will reach the goal of freedom in Birmingham and all over the nation, because the goal of America is freedom,” he wrote while sitting in jail.

And he did not stop there, for King understood that some things were universal. If Blacks were recognized as American citizens with inherent dignity, then histories of colonialism, economic racism, war, poverty and violence could be overcome. This belief remains more crucially resonant in our own time, however distant we may feel from King’s life. His legacy is everywhere around us.