From KUT:

Signs at the Nehemiah Christian School encourage reading and “dramatic play.” Weavings and other artwork dot the walls, while plants with lush green leaves spill over terracotta planters.

Children sit around a small table facing Tamitha Blackmon, who runs this child care program out of her home in Far East Austin. She points to a wooden calendar and asks the kids to tell her the year and the month. They enthusiastically reply: “2023!” and “September!”

Blackmon was a third-grade teacher before opening the Nehemiah Christian School 10 years ago.

“The reason I came and dropped down to preschool, infants, toddlers and all of that is because I saw a reading deficit in teaching third grade,” she said. “So, I thought: Why not lay the foundation?”

The Nehemiah Christian School has the highest rating possible — four stars — from the Texas Rising Star Program, which evaluates child care centers and registered child care home facilities that are part of the Texas Workforce Commission’s subsidized child care program. But Blackmon said making high-quality child care affordable is nearly impossible these days. Providers are contending with inflation and high property taxes. They also face thin profit margins because what families can afford to pay doesn’t cover the cost of running this type of business.

“Saying we offer high-quality child care that’s affordable — those just don’t go together at all,” she said.

To keep child care affordable for the families she serves, Blackmon said she must pay employees less and, often, not pay herself at all. But that changed for awhile during the pandemic, when the federal government invested billions of relief dollars to keep child care facilities afloat.

“I was able to give my employee some COVID pay; I was able to give him a raise, which made things a lot easier for him to pay his bills because he has a family,” she said. “I was able to start paying myself something, so it made it a lot easier.”

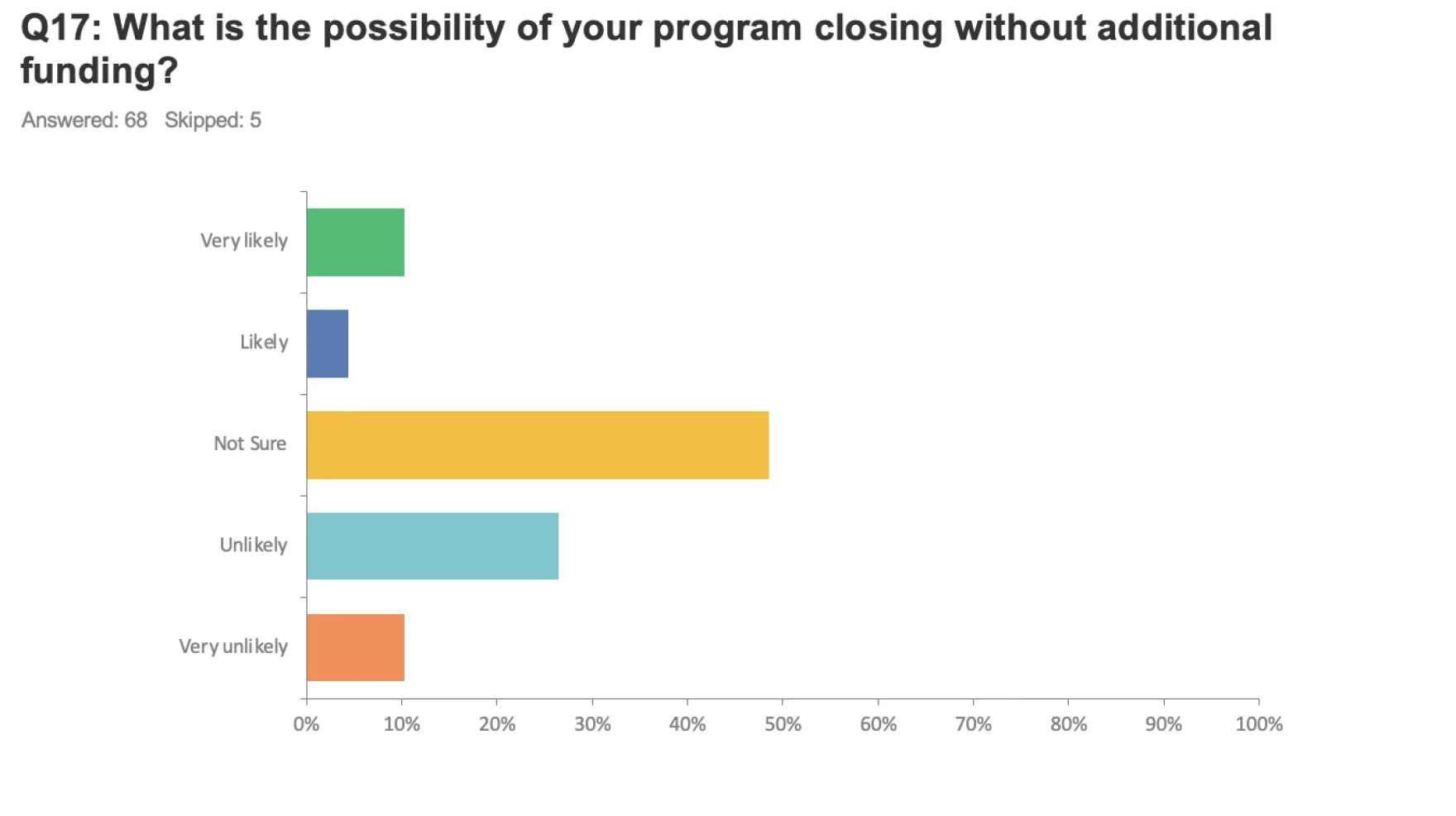

But that federal aid is running out, and child care providers — and the families who rely on them — face an uncertain future. Blackmon already received the last payment for her program. She said she’ll be able to stay open, but she expects other providers to shut down.

“I know that there will be some closures and that will have an impact on the facilities that remain open,” she said. “They’ll probably be at capacity and parents will not be able to find child care right away.”

Child care undervalued

Earlier this year, providers and advocates urged the Republican-controlled Legislature to invest in child care in anticipation of pandemic relief ending in September.

They called on Texas lawmakers, who had a nearly $33 billion budget surplus, to increase state funding for child care by $2.29 billion. They didn’t.

David Feigen, the director of early learning policy at Texans Care for Children, said the end of federal funding without an infusion of new state dollars leaves providers at a crossroads.

“They’re going to have to decide: Do I have to raise costs on the parents I’m serving? Do I have to lay off some staff that I can’t afford to keep? Am I going to have to close classrooms or am I going to have to close my program altogether?” he said. “Because they don’t have any funding to spare.”

Blackmon testified before the state Legislature about the importance of increasing funding for child care, especially as pandemic dollars run out. She told lawmakers every single one of them would be affected in some way if child care centers closed.

They did not heed those concerns.

“Sometimes you can be so far removed from things that you don’t even think about the day-to-day realities of it, and I think that’s what’s happening,” she said. “Especially if they don’t have children in child care.”

Patsy Harnage, who runs a child care center in North Austin, said she thinks another reason lawmakers did not increase funding for providers is that people fundamentally misunderstand what they do.

“We’re not babysitters and I think that’s the concept that they have,” she said. “We’re not babysitters; we’re early educators. We’re the kids’ doctors, we’re the kids’ nurses, we’re psychologists, we’re teachers, we’re their second moms.”

Harnage started Bright Beginnings, which also has a four-star rating from the state, in 2013. Her center serves more than 130 kids. She decided to launch the business after seeing a story on the news about high dropout rates.

“I determined that I needed to make a difference,” she said. “I needed to go out there, and I need to help these children, give them the tools that they need, to have a love of learning.”