‘The end of last year will be with us’: Are Texas schools any safer since the Uvalde shooting?

By Laura Rice

The beginning of a new school year means fresh school supplies, excitement over classroom assignments, new teachers, new friends. Possibilities.

But also anxiety: Will they like me? Will I get lost? Can I keep up?

And for today’s students, educators and school staff, there’s yet another layer of feeling baked in – a low-level, deep-in-the gut pain spawned from risk and dread. For parents, caretakers and loved ones, it can feel like a dice toss.

Will it be safe at school this year?

Will the alarms be false?

Will the drills be just drills?

Or will I get a text or a phone call – or hear the sirens, or the shots?

Will my community be the next Columbine … Newtown … Parkland … Santa Fe … Uvalde?

After all, in 2022, there’s no reason to think it can’t happen where you live. And in 2022, students just live with this reality. They have no choice.

“I can’t, like, imagine a time where we weren’t doing school shooter drills or doing some kind of lockdown in place,” said Manasi Saxena, a student in Houston. “When I was younger and just growing up, it always just seemed kind of normal. And it kind of took a while for me to notice and recognize that this isn’t normal, because, you know, I haven’t known anything else. I haven’t known a world where I’m not practicing what would happen if someone with a gun came into my school.”

– Houston student Manasi Saxena

A recent CBS News poll says nearly 3 out of 4 parents of school-aged kids are at least somewhat concerned about gun violence at their child’s school. More than 1 in 3 are very concerned.

Some experts say our fear of these events is out of proportion. Northeastern Professor James Alan Fox puts the actual risk of a mass shooting death for a K-12 student at about 1 in 5 million.

That’s one number. But Camille Gibson, executive director of the Texas Juvenile Crime Prevention Center at Prairie View A&M, has another:

“In terms of victims of school gun violence – not just mass shootings – since Columbine, we’ve had over 300,000 persons,” Gibson said. “And so we talk about the mass shooting cases because they get public attention, but they’re also just gun shooting incidents in general and in schools.”

Jeff Temple, a vice dean and the director of the Center for Violence Prevention at UT Medical Branch Galveston, noted that the United States is the only nation among high-income countries in which firearm violence is the leading cause of death – or even in the top five causes of death – for children, according to recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Parents in Canada or England or Australia, they don’t worry that when they send their kids to school that this is something that can happen,” Temple said. “We do. This is a uniquely American problem.”

This special report isn’t meant to stoke fear; it’s meant to acknowledge it. To give Texans a place to voice concern, to express frustration, to ask, very rightly: Even if mass shootings are not happening at epidemic levels, are they happening too often? Are they happening in this country – and in Texas – more than they should?

Patricia Lim / KUT

Twenty-one crosses were placed outside the Uvalde County Courthouse as a memorial for the students and teachers killed at Robb Elementary School in May.

Nineteen children – just 10 and 11 years old – are gone. Nevaeh Bravo, Jackie Cazares, Annabell Rodriguez, Makenna Elrod, Jose Flores Jr., Ellie Garcia, Uziyah Garcia, Amerie Jo Garza, Xavier Lopez, Jayce Luevanos, Jailah Silguero, Tess Mata, Maranda Mathis, Alithia Ramirez, Maite Rodriguez, Lexi Rubio, Layla Salazar, Eliahna Torres, Rojelio Torres.

The stories about them – the runner, the artist, the TikTok dancer – remind us that these weren’t just names on little white crosses. These were beloved children, sisters and brothers, each robbed from what should have been long futures.

And their teachers, Irma Garcia and Eva Mireles, dedicated their careers and ultimately their lives to those children. They weren’t supposed to be on the front lines – not in this way.

» In memoriam: A tribute to the 21 lives lost in the Uvalde school shooting

Erika Escamilla said her niece, who attended Robb Elementary School, “was crying to me, and she was saying that she heard the guy cussing. She heard like loud yelling, and she heard him cussing, and she heard a lot of loud bangs – the gunshots. She just put her hands over her ears and got down into a ball and she said, ‘Tia, it felt like I was having a heart attack. I was so scared, I didn’t know what to do.’ ”

We can’t talk about school shootings in Texas without talking about what happened on Aug. 1, 1966, when a sniper opened fire on top of UT-Austin’s iconic tower. Students assumed the noise was anything else; almost no one considered the possibility it was a gunman.

“Nobody could comprehend or conceive this happening,” said Milton Shoquist, who had graduated Austin’s police academy about six weeks before the tower shooting. “Therefore there were no plans to counteract something like this.”

But that was then – this is now.

“The first one that I can like thoroughly remember is the Parkland shooting. I think I was in middle school, yeah,” said Saxena, the Houston student. “So it was the first time that I was like able to thoroughly and completely sort of digest this information.”

We’ve spent a lot of time in the past several weeks talking about what happened in Uvalde – and rightly so. The loss of life was immense, and it has deserved our attention. Lexi Rubio’s mom, Kimberly, reminded a U.S. House Oversight Committee: Lexi deserves our attention.

“We don’t want you to think of Lexi as just a number,” Rubio testified in June. “She was intelligent, compassionate and athletic. She was quiet, shy, unless she had a point to make, when she knew she was right; she so often was. She stood her ground. She was firm, direct. Voice unwavering.”

It’s been important that we pay attention to exactly what unfolded at Robb Elementary – and why, and how – so that we can try to make sure it doesn’t happen again. There were more than a few missteps, from the failure to identify the risk of the young man who became a gunman to the law enforcement decisions that left him unchallenged for 77 deadly, horrific minutes.

There will be more digging into the details; more piecing together what went wrong and who is ultimately responsible.

But in the meantime, the summer has grown long. It’s time to get back to school. But how? How can we wrap our heads around sending beautiful children, dedicated staff back into buildings that keep becoming targets of terror?

What has Texas done since May 24, the day of the deadliest school shooting in the state’s history? Are schools at all safer now? It’s the question so many are asking, and it’s the question at the center of this special report.

Because we can’t let the numbness to the fear or the overwhelming enormity of the issues keep us from trying.

Can we find consensus? Can we identify solutions? Can we at least agree that we don’t want this to happen anymore?

We’ll hear from survivors, from experts, from students – and maybe from you.

Kimberly Rubio, a journalist with The Uvalde Leader-News, was at her desk on May 24 when the newsroom got the first police-scanner alert about the shooting at Robb Elementary – where she and her husband, Felix, had just attended her daughter’s awards ceremony that morning.

“We told her we loved her and we would pick her up after school. I can still see her walking with us toward the exit,” Kimberly Rubio told the U.S. House Oversight Committee. “In the reel that keeps scrolling across my memories, she turns her head and smiles back at us. And then we left. I left my daughter at that school, and that decision will haunt me for the rest of my life.”

Nineteen kids and two teachers lost; a community shattered by the trauma and divided by the reality of a bungled response. Angeli Gomez was among the first to draw attention to how law enforcement reacted at the scene.

“They could have done something – gone through the window, sniped him through the window, I mean, something,” she told CBS. “But nothing was being done. If anything, they were being more aggressive on us parents.”

Patricia Lim / KUT

Community members hold hands at a May 25 vigil for the 19 students and two teachers killed in Uvalde.

How can we – all of us – process what happened? Is it even possible? Jeff Temple, a vice dean at UTMB and founder of its Center for Violence Prevention, says it’s beyond our ability to cope.

“It is an insanely grotesque, horrible thing, and it’s just too difficult to really process it. And I mean that sincerely: I don’t think that we can totally figure it out,” Temple said. “We put it aside or distract ourselves, and, you know what, unfortunately, that might be the healthiest thing we can do right now.”

Cecilia Gullett graduated in Katy just hours after the shooting.

“I walked across stage to receive my diploma with the Texas and American flag at half mast, and all I could think was that I was doing something those 19 children would never get to do,” Gullett said, “that I survived nearly 12 years of Texas public education without witnessing the horrors of gun violence other than on the TV, and how lucky I was for that.”

Now, students across the state are returning to class – as are teachers.

“You know, as an educator, we all sort of look forward to the first day, the excitement of how our students are going to come into the space and all the things that we want to do and have them experience,” said Ovidia Molina, president of the Texas State Teachers Association. “But when we show up to the first day, we know that the end of last year will be with us.

“The threat is in the air, and preparing for how we will be receiving our students on the first day to help them feel safe – when we may not feel safe – is a struggle for our educators right now.”

And then there are parents.

“You know that they’ll be thinking about that as they send their children off, as they take them to school,” Molina said. “Instead of having an exciting, happy first day of school, it’s a fearful, anxiety-filled first day of school.”

Of course, there are those who don’t have to imagine what it’s like to have a shooting in their communities – because that nightmare has already happened.

– Ovidia Molina, president of the Texas State Teachers Association

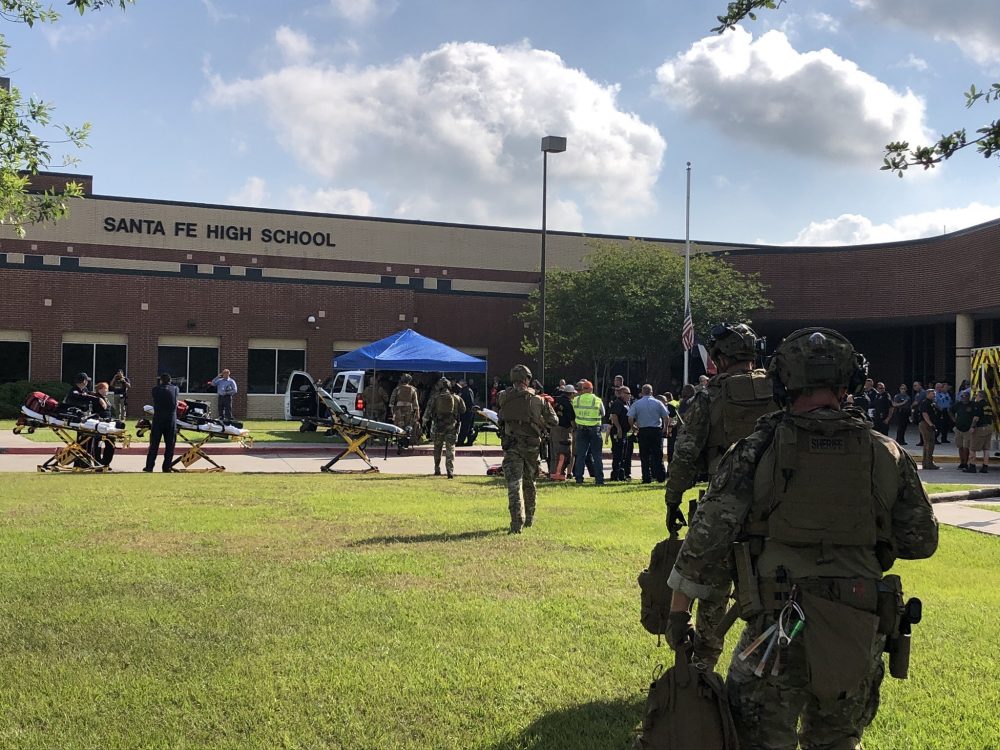

Harris County Sheriff's Office via Twitter

Law enforcement agencies are deployed at Santa Fe High School on May 18, 2018, after a mass shooting that left 10 people dead.

Flo Rice was a substitute teacher at Santa Fe High School. She took the job because she wanted to support the district where her kids went and get to know the community better. But she says she was always aware of the risks.

“I did look around, and I would always think about the furniture in the classroom,” she said. “What could I use to block a door? Those thoughts went through my mind, I guess, every single day.

“You think about these things, but if they actually happen to you – it’s still just surreal. You cannot fathom it.”

On May 18, 2018, Flo woke up her husband, Scot, with a phone call to tell him she’d been shot.

“We were exiting the building; we thought it was a fire alarm. And when I heard the first shot, it was so loud, so deafening, it was literally disorienting to me. I thought it was a bomb,” Flo said. “And then even in the next shot – which was me; I was shot and I felt myself falling – I still was thinking it was a bomb and it was a bomb blast.”

It wasn’t until Flo tried to sit up, looked and saw a fellow substitute from her room, Ann Perkins, lying a few feet ahead of her, that she then saw the bloody bullet holes in her legs.

“That’s when I realized I had been shot; it was a shooter. There was someone literally feet from me who was hunting us,” she said. “You just can’t imagine the fear that overtook my body.”

She kept dragging herself forward.

“I could hear the glass falling. And every time I would hear the sound of the glass, I was thinking that he was looking out the window with his gun and going to shoot me again. It was just terrifying.”

At home, Scot told their daughter to get in the car – they were going to the school, where her mother had been shot.

“I didn’t know at that time whether Flo would make it or not, and I wanted to make sure that her daughter had the chance maybe to see her before she died. I had no idea what was going to happen,” he said. “Finally, I was able to find her behind the school, and with the help of an officer that was standing near her, put her in the car. I was able to get her to the hospital before she bled out.”

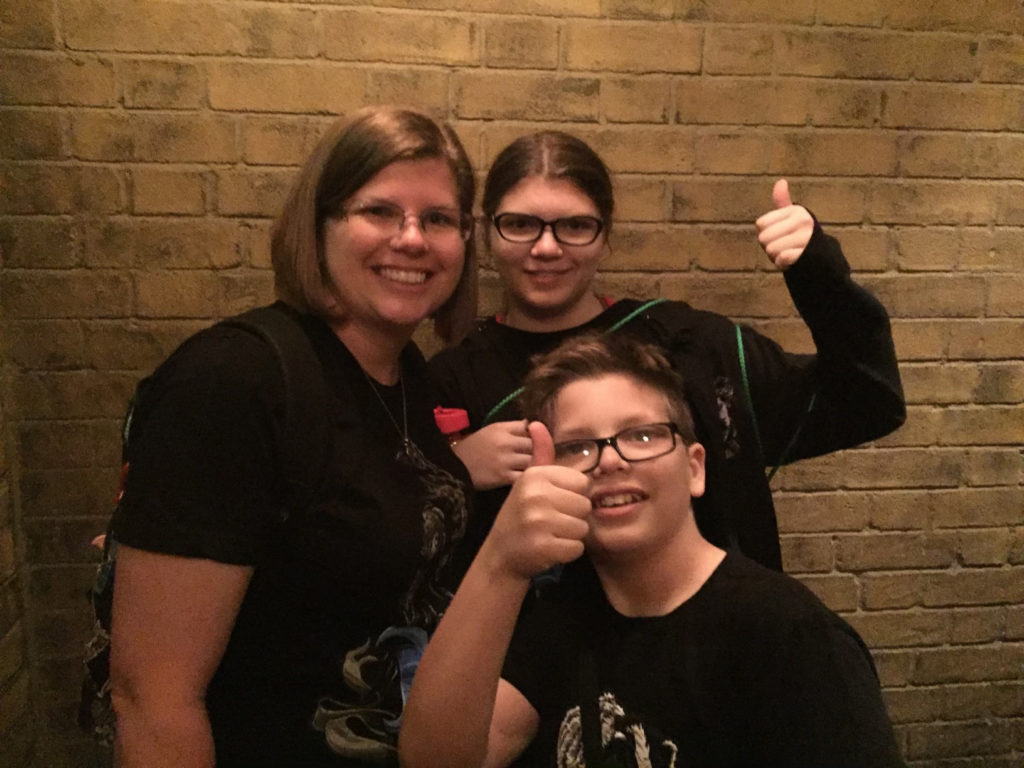

Flo and Scot Rice

Eight students and two teachers did not survive. Flo and Scot lead different lives now than they used to.

“The pain never goes away for her, and psychologically, she lives with every day the nightmares of the shooting; it keeps you up at night,” Scot said. “And there’s always something to re-trigger the anxiety and the trauma, with a new shooting, it seems like, every day. So it’s been a long, long four years of continuous trauma and anxiety.”

» From NPR: 4 years after Santa Fe school shooting, ‘There is still a lot of pain’

Scot and Flo think about Santa Fe every day – but how long did it take for the rest of us to move on? How soon will we forget Uvalde, the state’s deadliest school shooting in history?

Students taking their inaugural trips into a classroom this fall will soon be experiencing many firsts: sporting a full-size backpack, eating in a lunchroom, standing in line and raising their hands. But even our youngest kids will also learn things in school that many of us never had to consider.

Asya Ardawatia

Asya Ardawatia, a junior in the Houston area, says she can’t even remember her first active shooting drill, “because it’s like, you know, you can’t remember the first time you walked in the park, because it’s so often, it’s so regular and you’ve been doing it for such a long time that like, I can’t remember the first time.”

Camille Gibson, interim dean of the College of Juvenile Justice at Prairie View A&M University, said one thing we’ve learned from a number of mass shootings is that children who were in the room with the shooter have said they played dead to survive.

“You need to think about how to convincingly play dead under extreme stress,” she said. “And it’s unfortunate, but if we’re going to continue to have guns in proliferation in society, then that needs to be a part of the school safety training.”

Ovidia Molina, president of the Texas State Teachers Association, said students and teachers are facing a life-or-death situation “where it could be us any single day” because nothing has been done since Uvalde.

“We’re going back this school year with no concrete changes from the state. Our school districts are trying to figure out how we can do it,” she said. “You know, we are having safety audits. But these safety audits are like surprise attacks. They’re just trying to make it seem like the state is doing something about it. But having surprise attacks doesn’t do anything but remind us that we are in danger.”

Jeff Temple from UTMB agrees there’s something to that.

“We need to get rid of active shooter drill altogether,” he said. “They have little evidence that they even work. And the risk, the cost of doing this and traumatizing our kids and our families is way worse than any hypothetical benefit that we could receive.”

And his advice on how frank our conversations with kids on this subject should be follows that same line of thinking.

“I think we be honest with them in an age-appropriate way that there are bad people out there and sometimes they do bad things. But there are also really good people at your school and at home that are going to do everything in their power to prevent these bad people from ever doing anything,” Temple said. “And be honest about risk, which is very, extremely low risk of anything like this happening at their school.

“Schools are still the safest place for kids to be. They’re, by and large, extremely safe. And for many kids, they are the safest spot for them – safer than their homes, safer than the streets. So, you know, if I’m a parent out there, I have kids in school, I [have] full confidence that when I take my kid to school, I’m taking them to a very safe place.”

Gabriel C. Pérez / KUT News

Bedichek Middle School in South Austin.

Still, there’s no doubt there’s room for improvement. Flo Rice says basic changes, like having a phone that works to call 911 and being able to lock a door, could have saved lives in Santa Fe.

“That shooter would not have been able to get into the art rooms that day and kill all those children – the substitute couldn’t lock the door,” she said. “It was a substitute. It was all substitutes killed that day, as far as the teachers. They couldn’t lock doors.”

She and her husband, Scot, have spent the better part of the four years since the Santa Fe shooting working for change.

“Once something so horrific like this happens – that’s all you have really left is to think, ‘Okay, we’re going to use this to make sure it doesn’t happen again,’” she said. “That’s your focus, because it’s just too horrific to think of the alternative.”

And they’ve seen Texas move on from the tragedy.

“I’ve really lost faith in our Texas Legislature,” Flo said. “I’ve totally lost faith in them.”

– Flo Rice, who survived being shot at Santa Fe High School in 2018

In 2019, a year after a shooter injured Flo and killed 10 people at Santa Fe High School, the Legislature passed Senate Bill 11 – which was supposed to expand school safety measures.

“We were happy. I was really relieved. Thought something had been done to help our kids and keep them safe,” Flo said. “But what we did not know was that there was no teeth in this bill. We started hearing that these schools were not going to implement any of the requirements, and we really didn’t understand how they would just deny doing this.

“But we found out there was no way to hold them accountable. Nothing. There was no governing body that said, ‘Okay, you have to do this. And these are the consequences if you don’t have a phone that works, if the substitutes don’t have keys to lock a door.’ There’s literally nothing in place to hold them accountable. It was just – I feel like it was just for show.”

» Texas’ school security efforts following 2018 Santa Fe shooting have largely ignored gun safety

And worse, they saw some of the same things they were fighting to prevent unfold in Uvalde.

“Doors that didn’t lock, with people who didn’t go into lockdown. They didn’t announce a lockdown. They’ve had four years since Santa Fe to make the changes and to pay attention to what’s going on,” Scot said. “So it just seemed very personal, I guess. Because we really wanted to keep this from happening again. And you’re hopeful every time you work with your politicians and legislators that they are doing the right thing and that people are paying attention.

“It just breaks your heart to see these families suffering like you did and knowing what their future holds.”

When we consider how we can create long-term change to prevent mass shootings in schools, a few topics keep coming up: The hardening of schools, mental and behavioral health access and interventions, and gun laws.

Things can get pretty divisive pretty quickly. So let’s start with what we can agree on – Texans don’t want another Uvalde or Santa Fe.

“We’re all so incredibly desensitized to this. I’ve seen my classmates and my peers just, you know, we’re tired. But it’s just become a part of life for us. And I feel like we need to be told that this is not normal,” said student Manasi Saxena, who’s also an executive director of March for our Lives Houston.

“We are just trying our best to stop this violence, especially in our schools. We are not trying to take away anybody’s rights,” Saxena said. “We are just trying to, you know, keep our right to go to school and live in a safe environment.”

So does hardening schools make them safer? We asked Texas Standard listeners for comments and questions on this topic.

“We do need to beef up security,” said Wayne Tubbs of Crockett, Texas. “We need to get everybody more involved in putting a stop to school shootings immediately. Before any more kids get hurt.”

Jorge Sanhueza-Lyon / KUT

School marshal trainees go through a simulation of an active shooting at an elementary school in Pflugerville in 2018.

Some experts agree there may be some best practices all schools should implement. Prairie View A&M’s Camille Gibson supports limited access points at schools. And she thinks smart building plans make sense – for example, no glass walls that someone could drive a car through.

She also says any efforts taken in the first days of the school year – all that attention to detail – need to be maintained.

“There has to be a deliberate effort to maintain a high level of security in the school environment and not fall to the human tendency to slack off,” she said.

This point underscores what Santa Fe shooting survivor Flo Rice has said about training substitutes – even when they come on in the middle of the year or after a new training has been done.

“I mean, usually I was just handed a roster for the day and sent to a classroom, you know, and you just figure your way around. That’s not appropriate,” she said. “I mean, you need training [to] know where the classrooms are, you need training in what to do in an emergency situation, you need keys. I mean, these things, if you want to protect your kids, then that’s what you need to do.”

So what about what Texas lawmakers have often proposed – arming people in schools? The experts we spoke to are split on this.

UTMB’s Jeff Temple said research shows that added police and guns only increase the rates of violence. But Gibson said she does think somebody in the school needs to be able to respond to an active shooter threat.

“That hasn’t always been my view. But I think that’s the day that we’re living in,” she said. “But arming teachers? No. The teacher personality and the person who’s willing to shoot somebody – they’re not the same persons. And that’s just basic psychology.”

But Asya Ardawatia, a student and March for Our Lives Houston leader, says she’s lost confidence in those armed to protect her.

“A lot of campuses in my district have police officers. But I feel like, you know, with the Uvalde shooting, we saw how like, the police officers there, they were very trained. They had a lot of protection. They had their own weapons to counter the mass shooter, yet they did nothing,” she said. “And I feel like that’s really what scares me, is that like, if the law enforcement in my campus fails, then we’re all in danger.”

She’s not wrong, Texas Police Chiefs Association President Jimmy Perdue told the Texas Standard.

“We don’t believe that what happened in Uvalde was an equipment or a training issue; it was a commitment issue,” Perdue said. “We all know, as officers, what we are required to do and what we should do. And in that case, we failed to do so as a profession. We failed the citizens of Uvalde. And we are trying to do our best to make amends with that going forward.”

But Texas State Teachers Association President Ovidia Molina offers this word of caution when it comes to the so-called hardening of schools:

“We are just putting the blame and the solution-finding back on our educators and our school system,” she said. “But we can’t solve this problem. We need help from the governor.”

So let’s turn to another solution often broached by lawmakers – investment in mental health resources.

“I think that every child deserves to have the ability and the access to mental health resources,” Saxena said.

Every person we spoke to agreed – but they all offered a ‘but.’ Temple put it most starkly: “Mental health is often the boogeyman when it comes to both everyday gun violence and mass shootings.”

He said people with diagnosed mental health issues are much more likely to be victims than perpetrators of violence. Still, Gibson says there’s an opportunity to do a lot more in schools.

Patricia Lim / KUT

Clear Fork Elementary School in Lockhart.

“In Texas, we seem to want to fool ourselves that there is mental health care going on for young people in schools,” she said. “I’m a part of the Texas Mental Health Task Force. And, basically, what counselors across the state of Texas have said to us is that, no, there’s hardly any mental health work going on in K-12 schools in Texas.”

A major factor is a shortage of people with credentials to do the mental health work, she said. Texas is seeing counselor-to-student ratios of 1 to 650 and 1 to 700, when state law says it should be 1 to 350.

“The counselors who are there are dedicated and want to do the work. But they’re not able to do the work because of the shortage of school personnel,” Gibson said. “So they are monitoring students in hallways; they are doing a lot of testing; they’re doing a number of things. So in Texas, if people are saying that we’re doing mental health work in the schools, the reality is we are not, because we don’t have enough people to do it.”

Still – it may be more accurate to label what we need as behavioral health. Gibson said school shooters tend to have misogynistic views, have been victims of bullying or other abusive relationships, and often use violent language. She said schools need to be able to put warning signs together.

“So when folks in the academic environment and students see these potential trends, to whom do they communicate?” she asked. “And hopefully there’s an effective committee that knows how to make those decisions.”

And Temple said we should invest in all Texas students when it comes to healthy relationships.

“We need to revamp our education system to where every year, starting in kindergarten and through high school and post-high school, into trade school and college, that every single year they get a semester-long or a year-long course related to social-emotional learning, healthy relationship skills,” he said. “And that will absolutely reduce the amount of violence in general and firearm violence in particular. It will cost a lot; it’ll be tedious; it’ll piss a lot of people off because we’re going to get away from the typical things about education.

“But I come back to that and remind people that if we can make people healthier and happier, then they’re going to be better students and better future taxpayers. So it is fiscally responsible, is what I would argue, and it really does need to happen.”

– Camille Gibson, executive director of the Texas Juvenile Crime Prevention Center at Prairie View A&M

Renee Dominguez / KUT

Ofelia Rodriguez and her son, Thomas Rodriguez, join the teacher's union and other organizations in a May 31 protest demanding Ted Cruz stop gun violence with common-sense steps in the U.S. Senate.

But if talking about healthy behavior is going to ruffle feathers – then what can we say about the elephant in the room?

Gibson: “Guns and young people are not a good idea.”

Ardawatia: “We need to see more gun safety laws enacted, common sense gun laws, red flag laws.”

Scot Rice: “There’s no reason why someone 18 to 21 can’t wait to be a little older and a little more mentally mature before they’re able to buy a weapon.”

Molina: “The majority of the shooters have been young men who, if the age limit was raised to 21, would not have access.”

Temple: “If we reduce access to guns, we will reduce mass shootings and ‘everyday gun violence.’”

But what’s the real appetite for this change – among everyday Texans and among elected officials?

Last Friday would have been Kimberly Vaughan’s 19th birthday.

“We were rocking and rolling,” said her mother, Rhonda Hart. “She was 14 years old. She was in high school. And on May 18th, in 2018, in Santa Fe, a dad left his guns in the closet, and his son wasn’t feeling well. And the kid got the guns and went and killed 10 people in his art class.”

Including Kimberly, the youngest victim of the shooting.

Kimberly Vaughan was working toward her Girl Scout Gold Award — the organization’s highest achievement.

“She was a trip. She loved Girl Scouts. She was going to get her Gold Award. She had been in scouts since she was in kindergarten. She loves to read. She loves cats. She loved her little brother,” Hart said. “And like, she was always at the library. She always had two really thick books with her. Like we would go out to run an errand, ‘You only need one book.’ ‘No, Mom, what if I finish this one?’ Like, ‘Okay, fine, fine.’ “

Kimberly wanted to be a sign language interpreter – but she never even got to turn 15. Hart said it was heartbreaking to watch it unfold again in Uvalde.

“Bloody hell. Like, I was in the room when Greg Abbott told us that our shooting would be the last school shooting in Texas,” she said. “And I’m so mad for those families, and like I’m texting with some of them now and we’re becoming friends and we have that bond of ‘We’re in the Dead Kid Club’ and, like, I’m so mad for them.”

So: Are Texas schools any safer now than they were during Uvalde?

Santa Fe shooting survivor Flo Rice says no.

“Parents need to know your kids are not safe. I firmly believe it. No matter what the school is telling you, you should go up there, you should take a tour, take your checklist, get information from the Texas School Safety Center on what they should have in place and look for yourself,” she said. “Demand they give you a tour, check those logs, ask questions. Ask who has keys. Ask what happens. ‘Does this phone work in this classroom? Can I call 911?’ I mean, you’ve just got to do the work yourself to make sure that your kids are safe, because no one else is doing it.”

On the state level, there hasn’t been much movement – and it’s past the time for conversation, says Ovidia Molina of the Texas State Teachers Association.

“After every tragedy, we hear of how schools are going to be supported. And then, as the story grows old – and it’s very painful to say that, ‘as the story goes old’ – those promises of support sort of disappear,” she said. “And so we hope that this time will be different, that there will be changes that help our students and help our educators, help our communities. But we’re weary. We’re weary because we’ve heard this story before of how our schools are going to be supported. And it hasn’t happened.”

But on the national level, the U.S. Senate passed a landmark bipartisan gun safety deal this summer, led in large part by Republican John Cornyn of Texas.

The Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, approved by the House exactly one month after the Uvalde shooting and signed into law by President Joe Biden the following day, increased funding for mental health care and crisis intervention programs and closed a loophole in domestic violence law regarding who can have a gun following a conviction.

Though it was a fairly modest set of initiatives, the legislation was still more than enough to turn the GOP’s reddest members against Cornyn, said Texas Monthly writer Dan Solomon.

“By pursuing this, which is a topic that has been forbidden for decades, you know even though it’s very modest, it’s still the first,” Solomon said. “So I think there’s just a sense like, ‘Hey, maybe he’s not our guy; he’s not fighting the battles that we want him to fight for Republicans.’”

» From Houston Public Media: John Cornyn booed at Texas GOP convention

On the other side of the aisle, Democrats pointed out how much of the bill about guns was actually not about guns.

But Hart did see in the measure just a bit of what she’s worked hard for since her daughter’s death.

“I give them an A for effort because it was genuinely bipartisan, right? Like we got a solid 10 or 15 Republicans to sign onto that bill,” she said. “But it was also like, you didn’t do a fraction of the things that we wanted you to do, so we’re going to keep holding you accountable.”

She says she does get tired of the effort. She takes breaks and holidays off – but she won’t stop.

“Literally, I’m going to keep going because I want to do right by my kid,” Hart said. “If I get to save one more kiddo or one more adult from a gun, then I know I’m doing it. I’m doing it right.”

Rhonda Hart with both of her kids: daughter Kimberly and son Tyler.

Photo courtesy Rhonda Hart

Young people like Manasi Saxena and Asya Ardawatia are stepping up to help.

“I think that, yes, change can happen now. We just need to be incredibly, you know, resilient and try our best to make it happen,” Saxena said. “We need to put things into perspective. We need to understand that there are children dying, and we need to think about what is leading to that. I think that we all need to sort of just agree that change needs to happen.”

And there are many ways to help effect change, Ardawatia said.

“You don’t have to join an organization if you don’t want to. You can always just show your support by emailing, calling, telling your friends about it, raising awareness,” she said. “In your own way, I want you to raise your voice and make sure that you’re heard.”

Scot Rice says he’s focused on making sure others don’t experience what his family did in Santa Fe.

“When you go through one of these shootings, there’s like everything before that date, and then there’s everything after that date. It completely flips your world upside down. Everything affects you, where you go, if you can ever be around a balloon at a birthday party that might pop. Or if you can go to fireworks shows, or if you can be at a loud restaurant,” he said. “Every single moment of your life is different. And that no one should have to experience this, because a child’s right to go to school and to survive is more important than an 18-year-old’s right to buy an assault rifle.”

Join the conversation

Texas Standard is committed to keeping the attention on safer schools and communities, and we truly want you to be part of that conversation. How do we get to safer – together? Look for updates from us and opportunities to share your voice or attend events.

Uvalde: What’s Next

Written and hosted by Laura Rice

Audio edited by Leah Scarpelli

Guests booked by Rhonda Fanning

Digital story by Gabrielle Muñoz

Graphics by Wells Dunbar

Production support by Jill Ament, Kristen Cabrera & Alexandra Hart

If you found the reporting above valuable, please consider making a donation to support it here. Your gift helps pay for everything you find on texasstandard.org and KUT.org. Thanks for donating today.