President Biden’s plan to erase federal student loan debts for tens of millions of borrowers hit a legal wall Thursday, when a U.S. District Court judge in Texas called it unlawful and vacated the debt relief program.

The federal government quickly appealed the decision, which came just weeks before student loan payments are set to resume in January. The program was already on hold while a federal appeals court in St. Louis considers a separate lawsuit by six states challenging it.

The judge’s argument for striking down debt relief

In Thursday’s ruling, Judge Mark T. Pittman, who was appointed by former President Donald Trump, wrote that the program was a “complete usurpation” of congressional authority by the executive branch.

Pittman rejected the Biden administration’s arguments that, in a law known as the HEROES Act, Congress had already given the president the power to erase student loan debts in a time of national emergency and that the COVID-19 pandemic is just such an emergency.

“In this country, we are not ruled by an all-powerful executive with a pen and a phone,” Pittman wrote. “Instead, we are ruled by a Constitution that provides for three distinct and independent branches of government.”

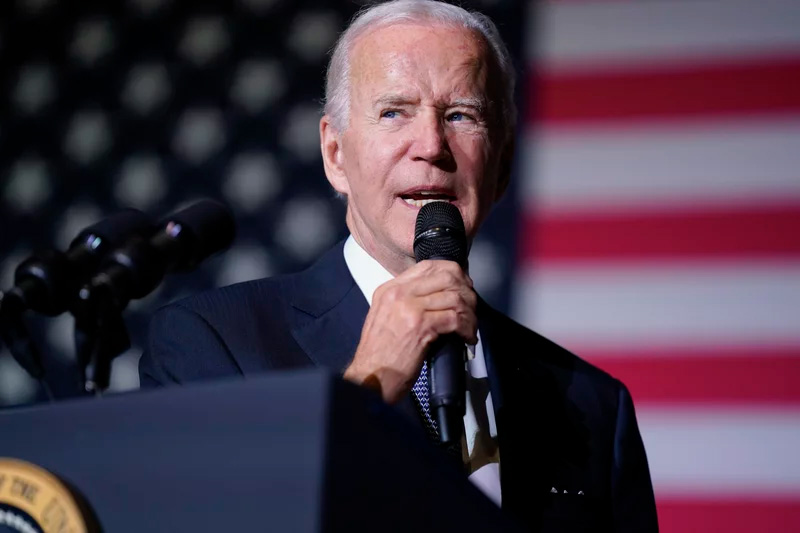

“We strongly disagree with the District Court’s ruling on our student debt relief program,” White House spokesperson Karine Jean-Pierre said. “The President and this Administration are determined to help working and middle-class Americans get back on their feet, while our opponents – backed by extreme Republican special interests – sued to block millions of Americans from getting much-needed relief.”

The appeals process could take weeks, leaving borrowers in limbo

Late Thursday, the White House confirmed that it had already appealed the decision. That appeal will go to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, which has a reputation as the most conservative of all federal appeals courts. From there, another appeal would land this case at the U.S. Supreme Court, which has so far refused to hear challenges to Biden’s relief plan. Borrowers likely won’t have a final answer on debt relief for weeks.

Meanwhile, student loan payments are set to resume in January. Back in September, U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona told NPR he hoped to process as many debt relief applications as possible before that payment pause ends on Jan. 1. Thursday’s decision makes it unlikely the department will reach that goal.

President Biden announced on Nov. 3 that close to 26 million Americans had provided the necessary information to the Education Department to qualify for relief and that the department was already on track to approve cancellation for 16 million borrowers.

Now, the department cannot cancel those loans without a reversal of fortune in the courts.

The lawsuit at the center of this decision

The case at the center of Thursday’s ruling was brought by the conservative Job Creators Network Foundation on behalf of two federal student loan borrowers who believe they were unfairly excluded from relief.

One borrower’s federal loans are held by a commercial lender, not the U.S. Department of Education, and don’t qualify for relief. The other borrower does qualify for $10,000 in relief but believes, because he is currently low-income, that he should receive the same level of relief – $20,000 – as borrowers who were low-income at the time they attended college.

The plaintiffs argued, among other things, that the Biden administration didn’t follow federal rules and should have allowed borrowers, and the general public, to voice their concerns about eligibility before the program was rolled out, though the administration countered that the HEROES Act specifically allows it to forego this kind of process.

“This ruling protects the rule of law which requires all Americans to have their voices heard by their federal government …” said Elaine Parker, president of the Job Creators Network Foundation, in a Thursday statement. “We hope that the court’s decision today will lay the groundwork for real solutions to the student loan crisis.”

But borrower advocates and some legal experts were quick to find fault with the judge’s decision.

“My first response was, this is motivated reasoning by a judge who wants to come to this result. The legal analysis is flawed,” says Luke Herrine, an assistant professor of law at the University of Alabama.

Persis Yu, managing counsel at the Student Borrower Protection Center, says there’s an important disconnect between the harm the plaintiffs alleged — not receiving the debt cancellation they believe they should have — and the court’s remedy: denying cancellation to all federal student loan borrowers.

“I like to think of this lawsuit as, like, the toddler problem. If I can’t have it, you can’t have it either,” says Yu. “And that’s not how the law works. And it’s not how the courts should apply the law.”

There are other lawsuits to stop Biden’s loan relief plan

Pittman’s decision catapults this case to the front of the line of cases opposing debt relief in federal court.

In late October, a federal appeals court temporarily blocked Biden’s relief plan before it could go into effect, so the court could consider a different suit, filed by six states – Nebraska, Missouri, Arkansas, Iowa, Kansas and South Carolina.

The states argued that a handful of state-based loan servicers that manage old, privately-held federal loans, would be hurt financially if borrowers were allowed to consolidate these loans and qualify for debt cancellation.

That suit had been dismissed by a U.S. district court judge in Missouri before the plaintiffs appealed to the 8th Circuit, which has yet to weigh in.

How we got here

In the 2020 presidential election, Biden pledged to cancel at least $10,000 per person in college debt.

Biden finally announced his loan relief plan in August, promising to cancel up to $10,000 for borrowers who did not receive Pell grants, and $20,000 for those who did.

Twenty-two Republican governors wrote Biden a letter in September challenging his authority to go forth with the forgiveness plan, and the Congressional Budget Office later estimated the initiative would cost $400 billion over the next 30 years.