This week’s leak of a Supreme Court draft opinion that would overturn Roe v. Wade put new attention on the issue of abortion access some 50 years after the decision that legalized the procedure in the United States. But even in the years after Roe, people still faced challenges to getting an abortion.

A new book focuses on people who sought abortion care and those who assisted them by escorting them to and from clinics.

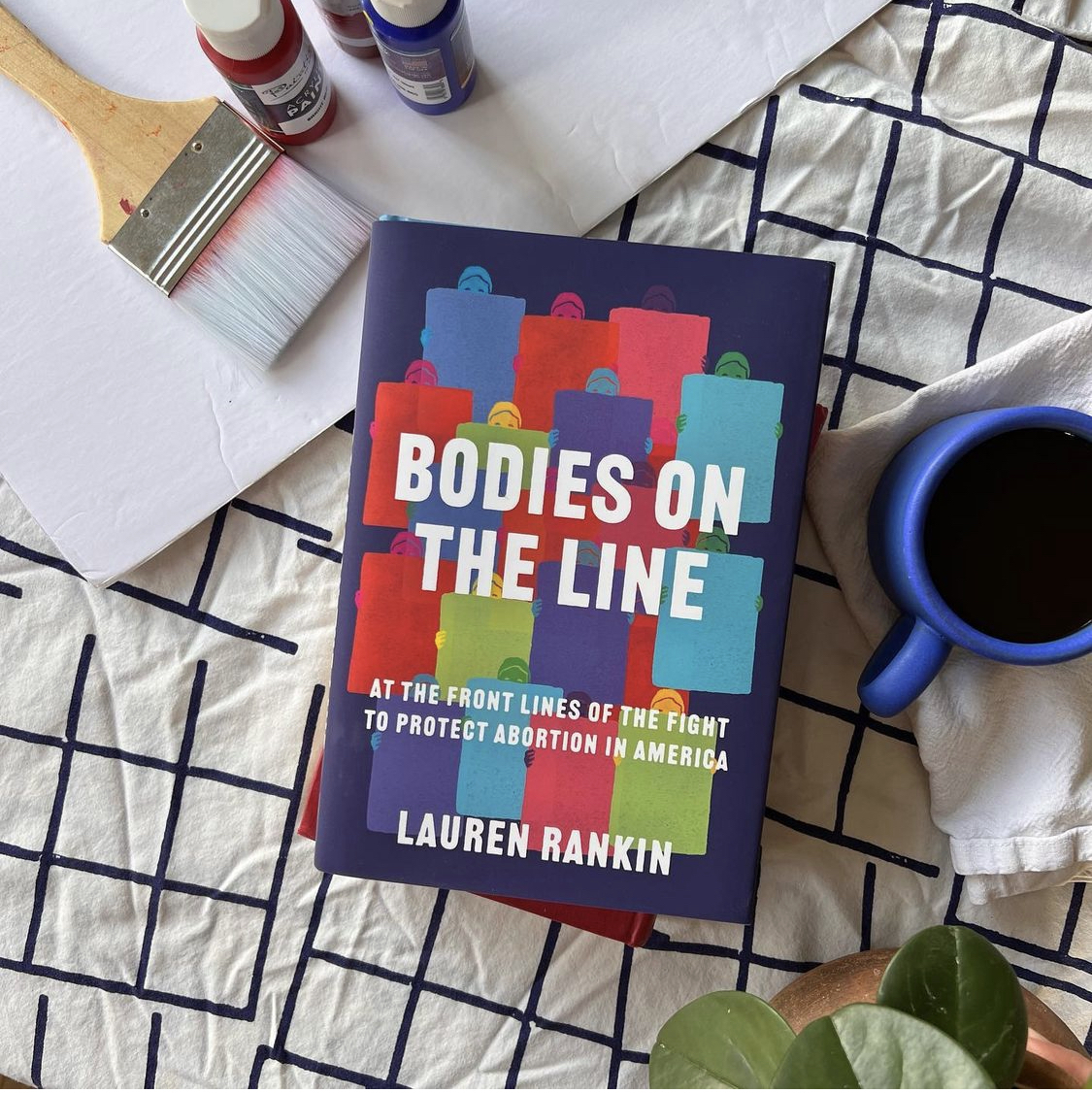

Author Lauren Rankin documents the rocky and, at times, deadly history of abortion rights, and the stories of workers on the front lines who are seldom discussed in coverage of reproductive rights. Her new book is “Bodies on the Line: At the Front Lines of the Fight to Protect Abortion in America.”

Rankin told Texas Standard that the practice of escorting women seeking abortion care to clinics began as early as 1978, in Fort Wayne, Indiana. It began when abortion opponents started protesting at clinics, confronting or blocking those seeking care. Rankin says local law enforcement did not intervene in the confrontations, and local people began volunteering to escort patients.

“They started walking patients past the protesters,” Rankin said.

Escorts began working at more clinics as protests grew and as word of mouth created a network of volunteers. Groups like Operation Rescue escalated protests around the nation, and Rankin says those groups were often “blatantly breaking the law” in order to interfere with clinic patients.

Rankin herself served as a volunteer clinic escort for six years in New Jersey.

“My experience doing that kind of volunteer work and seeing the human stakes of abortion up close and quite literally in your face, it shifted how I thought about this issue, and I realized no one really talks about what it feels like to actually get an abortion, what it looks like for a patient to have dozens, maybe hundreds or even thousands of people screaming in your face that you’re a murderer,” Rankin said.

The stories Rankin wanted to tell in her book include clinic escorts who faced intimidation and even bomb threats. She says media narratives aren’t nuanced enough to capture the reality of those experiences.

“Clinic escorts play a really invisible kind of role, intentionally,” Rankin said. “They don’t try to put themselves in the middle of this debate or fight. They just really want to be able to be there to facilitate health care.”

In the late ’70s and early ’80s, escorts avoided confrontations with protesters.

“Clinic escorts really were mostly focused on patients,” Rankin said. “They would walk patients; they wouldn’t really interact with protesters.”

Later, when protester activities escalated and included physically blocking access to the clinic, escorts took a more forceful role.

“It really became this sort of interesting dance between clinic escorts who would try to get patients into the door and clinic defenders who would manually set up their own bodies as barriers against the protesters to create walls with their bodies, and chains so that they could try and keep the clinics open,” Rankin said.

Law enforcement often would not help clinic operators stay open or stay safe, Rankin says.

“Law enforcement, time and again, whether it’s by apathy or antipathy, has really failed to actually show up and do anything meaningful for clinics,” Rankin said.

She says abortion opponents skillfully over-matched law enforcement by sending thousands of protesters to locations that had limited police resources.

In 1994, the Federal Access to Clinic Entrances Act, or FACE, made it a crime to block access to clinics that offer abortion services.

“If you call law enforcement, as I did several times when I was a clinic escort, they show up and they just think this is a matter beyond them,” Rankin said. “They don’t want to deal with it.”

Rankin says escorting clinic patients was a way for her to “do something tangible.”

“You feel the gratitude, you feel the fear, the relief, all of the emotions coming from the person that you’re walking with,” she said. “And you understand that while I can’t change the law today, what I can do is make a positive difference in one person’s life by helping them see through on the decision they’ve already made for themselves.”

Rankin believes that it’s about humanity, too.

“Most reasonable people can agree you shouldn’t be screamed at,” Rankin said. “You shouldn’t have a camera shoved in your face because you want to get a health-care procedure.”