From Houston Public Media:

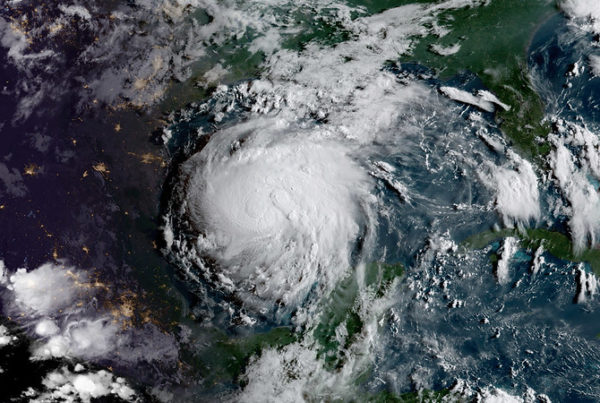

In two short years, Lina Hidalgo has led the third most populous county in the United States through hurricanes, petrochemical explosions and now an unforeseen pandemic that’s taken the lives of nearly 2,000 Harris County residents.

During her term, she’s also weathered a lion’s share of criticism, especially from state Republicans.

“Everywhere you see these draconian rules of locking down people and keeping businesses shut and destroying our country — it’s mostly Democrat governors, Democrat county judges, Democrat mayors,” Texas Lieutenant Gov. Dan Patrick said on Fox News last April.

Early in the pandemic, the governor’s office had also been critical of Hidalgo’s mask mandate that imposed penalties — and restricted her from implementing fines. Later on, Gov. Greg Abbott received praise for his own mask mandate, which also imposed fines.

“It’s challenging to see politics creep its way into disaster response,” Hidalgo said.

“Folks were just calling saying ‘Hey, I’m confused, what am I supposed to do. You’re saying one thing but I’m hearing a different thing from the state and a different thing from the federal government.’ So, it’s definitely one of the biggest challenges in the time of COVID, but that fight’s not over and the need for unity isn’t over, so we’re going to continue working at it.”

An International Education

COVID-19 is far from Hidalgo’s first experience with chaos and tragedy.

She was born amidst a bloody drug war in Bogota, Colombia.

“It was the time when you couldn’t go to the grocery store by yourself, because you had to leave somebody in the car, so that the authorities could make sure it wasn’t a car bomb,” Hidalgo said.

At 5 years old, she and her family moved to Peru to escape the violence, when her dad secured a job in Lima. She attended private international schools where she learned English and began to form her idea of government as she watched giants in Latin American politics fall from power.

She said she remembers her father meeting Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori at a ribbon cutting ceremony for a business.

“He managed to get a picture with the president and I remember (thinking) ‘oh my goodness, here’s the president… that’s amazing’. And then a few years later, he (President Fujimori) was indicted for corruption and bribery,” Hidalgo said.

Hidalgo said her experiences growing up in Peru — and later when she moved to Mexico — shaped her sense of how government officials should not behave, just as much as how they should. Then, when she was a teenager, she made what she calls her “most shocking move” — to Katy.

She said she marveled at her new public school, Seven Lakes High School.

“I had seen diversity, of course, but not like this, so that was beautiful,” Hidalgo said.

She said another notable difference was the quality of the public school system.

“Even for me as a teenager, I could tell that it was impressive that I was zoned to a fantastic public school where my teachers cared so much about me, where I was able to be a part of challenging classes, where there were great facilities, extracurricular activities and the sky was the limit,” Hidalgo said.

Though she had always attended quality schools in Latin America, they had been very expensive private institutions, she said.

Studying Democracy

Hidalgo went on to study political science at Stanford. There she learned why some government institutions — like public schools — were successful, while others failed.

She expanded her international experiences beyond the Americas.

She said she witnessed the “fragility of democracy” when she went to Cairo, Egypt to do research in the wake of the Arab Spring after President Hosni Mubarek stepped down from office.

“I saw this democratic opening and the quick closing and recognizing how fragile that is and how many institutions have to be in place for democracy to be successful. That really stuck with me,” Hidalgo said.

After graduation, she worked in Myanmar, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam for the media nonprofit Internews, funded by the U.S. State Department.

“I wanted to work on accountability, I wanted to work on transparency and I figured I was going to do that as an advocate, as a lawyer, as an activist,” said Hidalgo.

Lina Hidalgo interviewing in a village in Sarawak, Malaysia.

But ultimately, it was political developments in the United States — where she had recently become a citizen — that inspired her next big move: run for office.

“It had never occurred to me and then finally after the 2016 election I think a lightbulb went off in my head and many other women’s heads. And we said ‘hey this is a good idea, if Donald Trump ran and won, surely I’m qualified if he is.’”

Her Win

At 27 years old, Hidalgo defeated a popular Republican incumbent to become the first-ever female county judge — and the first Latina.

And, she said, that election was the first time her parents had ever voted.

Hidalgo’s win is proof that other Latinas can do it too, said Michele Leal, a consultant, former candidate for Texas House District 148 and part of the Latino Texas PAC.

“The young women that I mentor, mostly college students, I often hear them lament that they don’t feel like their vote, or their voice, matters because they are so far removed from the political system and the people who influence it,” Leal said.

She said she admires Hidalgo and recognizes what her run for office means for her mentees.

“It makes me so happy for them to see someone who shares similar experiences, as Latinas, as immigrants, as women, who didn’t take a traditional path to get there,” she said.

Inspiring other outsiders to get involved in politics is what Hidalgo said is one of her favorite parts of the job.

Judge Lina Hidalgo at the Women’s March in Houston in 2018.

“I hope that for people who are interested in politics, whether they look like me, have my background or not, that at least it tells them ‘hey you don’t have to be of a particular background to run and to go and work for your community. Go get it.’”

Hidalgo plans to run for reelection in 2022.