From KERA News:

People without health insurance in Collin County don’t have a public hospital to go to — and many of their options for free healthcare come with a message.

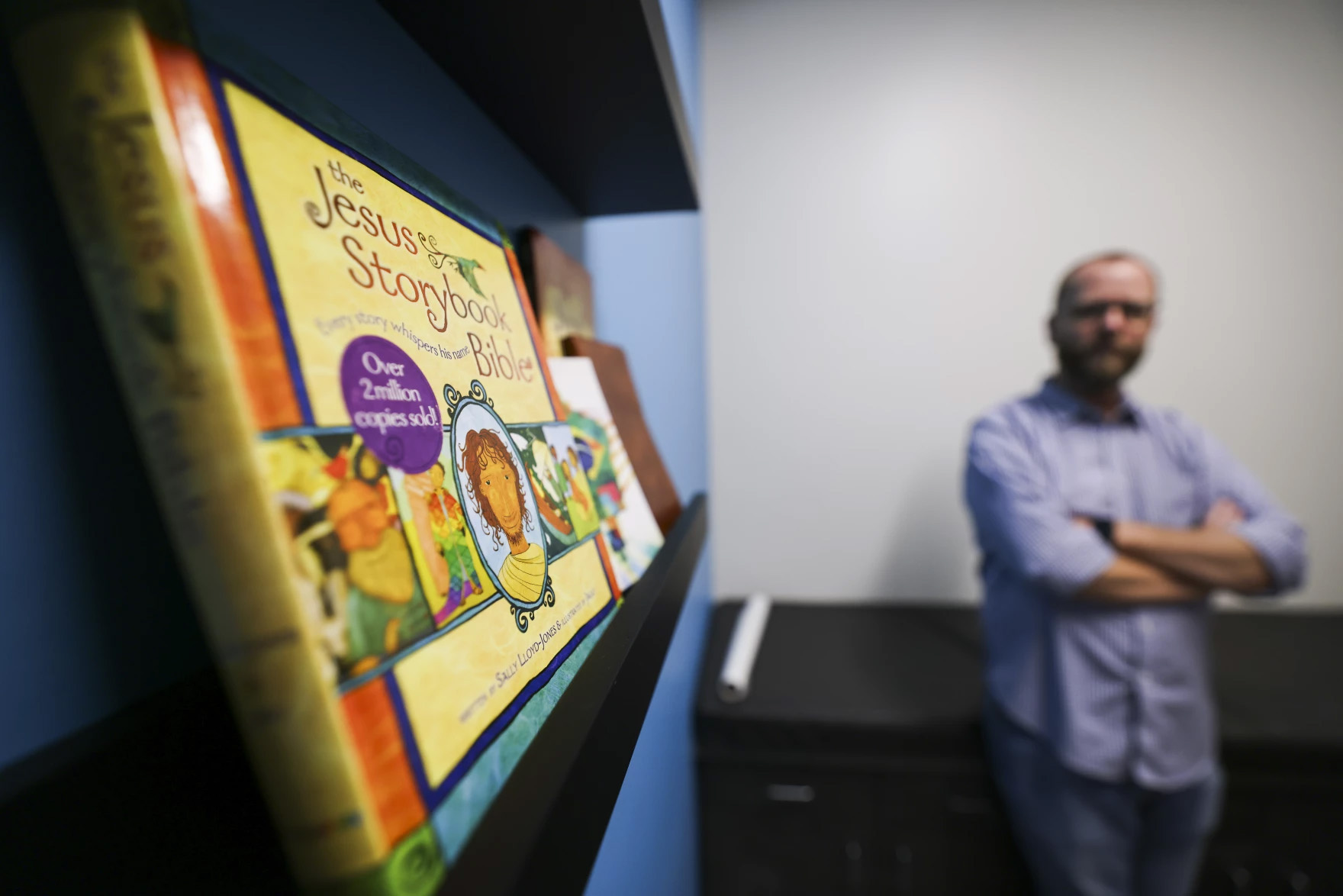

At CityBridge Urgent Care in Plano, patients listen to Christian worship music in the waiting room. There are children’s Bible story books in English and Spanish sitting on shelves in patient rooms — plus a Bible for the adults to read.

Chuck Bealke, the clinic’s director, said the urgent care blends spiritual care with healthcare.

“We’ll just ask them, hey, are there ways that we can be praying for them, and really just let them know that they’re cared for when they come in here,” he said. “Because we believe that everyone who comes in here has value and dignity and was created in the image of Jesus.”

CityBridge Urgent Care is one of the few options available to Collin County residents without health insurance. There’s no public hospital like there is in Dallas County, so faith-based groups like CityBridge Urgent Care are trying to fill that need.

Resource Gaps

WaterMark Plano — which later became CityBridge Church — founded the urgent care about five years ago. Bealke said the number of patients has grown by double digits each year since. This year, the clinic already has served more than 2,000 patients.

But that number could have been higher. Bealke said it’s not uncommon to turn away as many as ten patients a day.

“There are times when the clinic does have to close just because we don’t have enough providers,” he said.

People also come to the urgent care for help managing chronic diseases. But Bealke said CityBridge urgent care focuses on acute care — things like stomach bugs, the flu or COVID-19. Bealke said he refers those patients to Hope Clinic of McKinney, a primary care clinic supported by several churches that also serves the uninsured.

Andrea Naff, the executive director of operations at Hope Clinic, said the healthcare center does its best to fill the patients’ needs, but there are limits. Primary care doctors whose patients have insurance can refer them to specialists. But Hope Clinic has a harder time doing that.

Naff said a county hospital would fill that gap.

“Just because North Texas is affluent in many ways, I think it’s foolish of us to overlook what we could provide for those who are without in Collin County,” she said.

Some Collin County residents can see a doctor through the county’sindigent care program. They have to be at 100% of or below the federal poverty level to qualify. For individuals, that’s about a $15,000 annual salary.

There’s also Project Access, a partnership between the Collin County Commissioners Court and the Collin-Fannin County Medical Society. The nonprofit connects uninsured patients with doctors who’ve volunteered their services to the program.

Hope Clinic and Project Access both see patients who make up to 200% of the federal poverty level, an income of about $20,000 annually for individuals.

Collin County Public Health Director Candy Blair said the county doesn’t need a public hospital.

Blair said county hospitals struggle with resources and keeping up with technology changes. She also said higher healthcare costs are too of big a problem for the county to solve alone.

“It’s a federal issue, and there’s no possible way that the taxpayers can bear the burden of all of that,” she said.

Parkland hospital in Dallas gets about 40% of its budget from Dallas County taxpayers. Senior Vice President Mike Malaise said he doesn’t know exactly how many low-income Collin County residents end up at Parkland, but that it does happen. Parkland even has had patients from other countries show up.

Elected officials want the public hospital to only serve Dallas County residents.

“It’s a reasonable position,” Malaise said. “They can’t take care of everybody in 254 counties across the state.”

Greater Distance

Malaise said people who travel from surrounding counties to Parkland often are sent back home back home to get care.

But that might not be an option for everyone. Danelle Parker, the director of community health improvement for Collin, Parker and Wise counties, said many of Collin County’s rural towns lack access to primary care.

Parker said not going to a primary care doctor can exacerbate chronic medical conditions.

“Primary care is prevention, and it means you’re following up on your needs,” she said.

But that can be challenging for residents in Farmersville — Parker said there’s only one medical provider there. Surrounding towns like Anna and Princeton don’t have many options either, which means folks travel to McKinney or Plano for appointments.

Blair said she expects the areas in Collin County with fewer healthcare options will have more providers soon as the county continues to grow.

“You build it, and they will come,” she said. “And that has held true, especially for Collin County.”

Malaise said having to travel longer distances to see the doctor may mean that folks stay at home — especially people without health insurance.

“Nobody’s fired up to go to the doctor and hear what’s wrong with them and how much it’s going to cost to fix them,” he said. “And so you add in, it’s going to take me an hour to get there, and a lot of people just don’t make the trip.”

Getting there can also be an issue. Malaise said many of Parkland’s lower-income patients don’t have access to reliable transportation. He said it took one patient two hours on public transit to get from Dallas’ Pleasant Grove neighborhood to Parkland.

Not managing a chronic disease can make things worse — Naff said many Hope Clinic patients used to frequent local emergency rooms, which are required by law to treat patients regardless of their insurance status.

“Oftentimes, people who come here have before used the E.R. as their primary care, and that is very costly for taxpayers, for the hospitals,” she said.

Forward solutions

A public hospital isn’t the only solution. Malaise said Collin County could expand its indigent care program. The county could also pay a local hospital district to send uninsured patients there.

But he said the need for more healthcare options for the uninsured isn’t going to disappear.

“Collin County is growing into a heavily populated urban center,” Maliase said. “And as it grows, it’s going to continue facing challenges with social services on a scale that it probably hasn’t experienced in the past.”