Every year on her birthday, Shawna Hodgson and her brother drive out to East Texas, and they visit her grave.

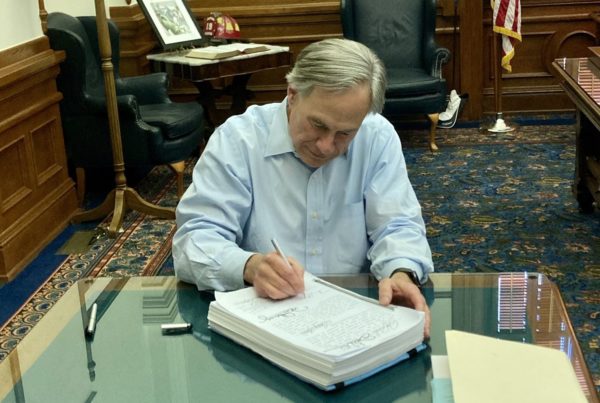

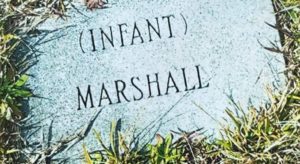

Hodgson was adopted soon after birth. Her biological brother is older than she is, and when their pregnant mother didn’t come home from the hospital with a baby one day, he asked questions. Their grandmother took him out to their family cemetery plot, and showed him a grave marked “(Infant) Marshall.”

That’s your sister’s grave, she told him.

“They told my brother that I had died,” she said. “He grew up 40-something years of his life believing he had a little sister that had died, so imagine his surprise when I showed up.”

The “Marshall” grave in the East Texas cemetery is next to generations of Texans. But Hodgson didn’t connect with her roots or birth mother until much later.

It’s something she said her adoptive parents haven’t been thrilled about.

“They were told at the time ‘she’s never going to know her birth family,'” Hodgson said. “‘They’re never going to come back in the picture. She’s yours. She’s a blank slate. Make her your own.'”

Like many states, Texas adoptees are issued a new birth certificate with their adoptive parents’ names. Their original birth certificate, which lists their birth parents, is sealed. And Texas born adoptees can’t access their original birth certificates until they’re 18. Even then, they have to already know the names of both of their birth parents. Otherwise, the adoptee will have to petition the court.

And adoptees say that creates confusion and sets up roadblocks later in life.

Hodgson, who grew up in Cypress, said it took years for her to access her birth records. Her birth mother was 24 years old and recently divorced when she was pregnant with Hodgson in the 1970s. Because Hodgson’s maternal grandmother refused to help care for both Hodgson and her then three-year-old brother, Hodgson’s birth mother gave her up for adoption. Feeling pressured by her family, her mother later told her she would have raised her if she had more of a choice.

Not knowing where she came from made Hodgson feel less grounded in her identity. When she turned 18, she expected that gaining access to her original birth certificate to get answers about her history would be easy.

Instead, she had to wait decades to find her birth family through DNA testing.

A gravestone in East Texas, which Shawna Hodgson said was used by her birth family as a cover for her adoption as an infant.

Struggling to access birth records isn’t uncommon for adoptees. Gregory Luce, an adoptee who founded the Adoptee Rights Law Center, had to go through a five-year court case to access his original birth certificate. Luce, an attorney based in Minnesota, said he finally felt tethered to the earth when the story of his birth was no longer a secret.

“The idea that your birth is secret and can not be known is something that many adoptees internalize,” Luce said. “They feel that they should be ashamed about their birth.”

According to the Adoptee Rights Law Center website, Texas is one of 17 states that restricts adoptees’ access to original birth certificates. Hodgson – who now works with a number of Texas adoptee organizations, including the Texas Adoptee Rights Coalition – has tried and failed since 2015 to to lobby the Texas Legislature to get a bill passed that would make original birth certificates more accessible in Texas.

In the 87th Legislative Session, Texas House republican Cody Harris, R-Palestine – who is also an adoptive father – wrote House Bill 1386 to provide adult adoptees access to their birth records without restrictions. The bill had bipartisan support, but failed to make it out of committee in the Texas Senate.

Hodgson said state Sen. Donna Campbell, R-New Braunfels, is a key reason for that. Campbell has blocked the bill in the senate since 2015.

“We come back year after year,” Hodgson said. “We work so hard for this, and we got this one person with so much power.”

Campbell, herself a mother of an adopted child, did not comment for this story. But she has previously cited concerns about birth parents’ privacy as her reason for not supporting the bill.

Hodgson, meanwhile, said the bill would allow adult adoptees private access to the information and would not make the birth records public.

Even if the state Legislature made it easier to access birth records, adoptees would still not have any legal relationship with their birth family, according to Karlos Dillard, an adoptee advocate and author of the memoir “Ward of the State.”

That’s common in states across the country. Dillard said he was abandoned by his adoptive family at 15, and spent two years on his own.

“We all think adoption as this wonderful thing, and this life-changing thing, but what about the adoptions that go bad?” Dillard said.

When he decided to go to college, Dillard hit a roadblock: in order to get financial aid, the federal student aid application required his adoptive parents’ tax information. He had to go through a lengthy process to prove his financial independence.

Later, as an adult, Dillard reunited with his birth mother and siblings. When his birth mother and sister died in a car accident, Dillard said he couldn’t be listed on their death certificates or help plan their funerals. Legally, his adoptive parents are still his parents.

Having his adoptive mother instead of the woman who gave birth to him listed as a parent on his birth certificate is hurtful, Dillard said. Changing an adoptee’s birth certificate, he said, can impact their sense of self.

Dillard has now made it his mission to annul his adoption, to remove his adoptive parents from his birth certificate and to restore his original birth certificate. But not every adoptee is able to do so, and the legal process is lengthy.

In Texas, adoption annulments have to be petitioned for through the courts. The court clerk forwards the information to the state registrar. If the Texas Department of Health and Safety determines the petition has merit, it will mail it to an attorney of record, who will return the corrected birth certificate to the department.

Jacob Cohen, an attorney at the Rainwater Firm in Houston, said he hasn’t seen an adoption annulment case in his ten years of practicing law, nor had he ever heard of his firm handling an adoption termination case in its 25 years.

As a family law practitioner, Cohen said there are certain laws he references in almost every case involving a child.

“Then there’s the other set, the rarely used, rarely cited statutes that don’t really come up because they’re for situations that are just so rare,” Cohen said.

Some child advocates argue that birth certificates shouldn’t be reissued when a child is adopted; In some cases, the process can essentially erase an adoptee’s origins, said Will Francis, the Texas chapter executive director of the National Association of Social Workers. Reissuing a child’s birth certificate with the adoptive parents’ names, he said, is a misguided attempt to create a new family.

“I think an adoptive family is a beautiful, wonderful entity by itself,” Francis said. “But it does not need to erase history to exist.”

If an adoptee wants to annul their adoption, Francis said, it should be an option.

Barriers to benefits

Children adopted out of the foster care system in Texas retain access to their benefits as wards of the state even after they’re adopted. These benefits include access to Medicaid until age 26 and state college and trade school tuition assistance.

However, those benefits only apply to youth adopted from foster care. Children who are adopted privately or internationally – who weren’t wards of the state prior to their adoption – must have their adoptions annulled in order to receive those benefits, or their adoptive parents would have to terminate their parental rights and relinquish the adoptive child to the state.

Even though there are resources for current and former foster children, few of them use those resources. Francis said the foster care system doesn’t prepare them to take advantage of free college or trade school tuition, or other resources.

“We have all these things that are no cost, and yet we don’t give them the guidance, knowledge or resources to actually obtain those,” Francis said. “Just because you have free access to school doesn’t mean you have anyone teaching you how to write an application. It doesn’t mean you know where you’re going to live and stay on campus.”

Child advocates say it should be easier for adoptees, foster youth and their families to access resources without having to jump through the systems’ hoops. Resources for families in poverty whose children are removed for neglect would ease the strain on the system, making adoption and foster care a rare resource for more serious cases of abuse, they argue.

If Hodgson’s birth mother had more resources, she wouldn’t have given her up for adoption.

Now Hodgson, who today has a close relationship with both her birth family and her adoptive family, believes people should take all of these factors into consideration.

“It’s the big question,” Hodgson said. “Who deserves to be a mother?’”