On average, five Texans die from fentanyl each day, according to the Texas Department of Health and Human services. Its an ongoing epidemic that’s been raging for years, with no signs of slowing down.

More and more often, those dying of fentanyl are the young – high schoolers and young adults whose lives had only just begun. A new project from the Dallas Morning News examines the scale, scope and impact of this crisis, and tells the stories of family members who have lost loved ones to the drug.

Sharon Grigsby is city columnist for the Dallas Morning News and one of the reporters on the project, called Deadly Fake: 30 Days Inside Fentanyl’s Grip on North Texas. She joined the Texas Standard to talk about the project. Listen to the interview above or read the transcript below.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: This project is quite expansive and as we all know, this is a statewide issue. But is there any reason to believe North Texas is a particularly hot spot for fentanyl trafficking and overdoses?

Sharon Grigsby: What the North Texas DEA boss, Eduardo Chávez has told us is that with so many of the most popular smuggling routes passing through Dallas – I-30, I-35, I-20 and I-45 – Dallas for a long time was just a pass-through point, but it’s now a major distribution point.

» RELATED: How does fentanyl get to Texas? Court cases tell us more about the path the drug takes

You spoke with an expert who said he’s alarmed by how uninformed Texans are. Could you say more about that?

Yes, that’s Dr. David Atkinson. He’s head of children’s health here in Dallas.

What he said is that we’ve not seen any drug screen come back positive for any opioid other than fentanyl since 2021. He believes that kids are certain they’re taking something else or their parents think they’re taking something else. Sometimes their parents aren’t even aware because fentanyl doesn’t show up on your basic tox screen.

As a result, either kids are getting addicted to it or they’re poisoned by a pill that’s disguised to look like something else.

Are we talking about pills that are laced with fentanyl or people taking fentanyl on its own?

So the “laced” word is really confusing out there. Even the DEA can be contradictory about its use of it.

The fact is, the DEA boss up here says they’re not seeing any pills that are laced with or that include fentanyl. It’s straight up fentanyl.

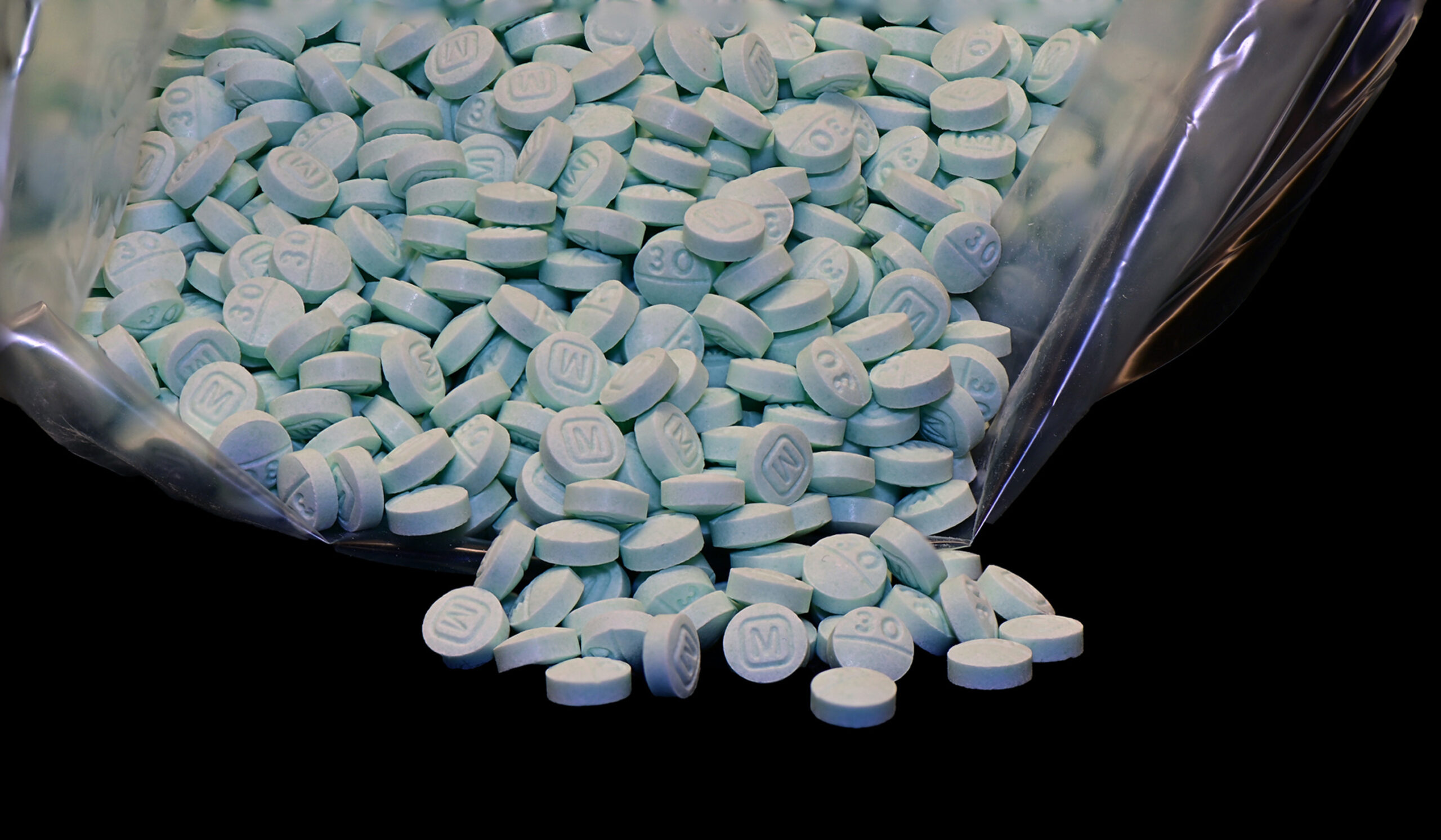

It’s where an oxycodone – which on the street, that’s an M30. It’s the very familiar light baby blue pill. It is actually all fentanyl that has been pressed by a machine to resemble something it’s not. So it’s just fentanyl, plus the fillers.

» RELATED: Fentanyl’s rise, distribution tied to growth of social media

I think I may have mentioned this in a conversation about fentanyl before in our broadcast, but once I was in an ambulance and I saw that there were gloves that were set aside for fentanyl, and I asked about it, and the EMT in the ambulance said fentanyl is so deadly that it can actually creep through normal thickness gloves that they use for when they’re providing medical attention. They need thicker gloves if they even suspect fentanyl because of how easily it’s absorbed by the skin. I’m shocked that something so deadly would appear in a pill form that people might take.

So there are a lot of myths out there about fentanyl, and I fear that EMS person was speaking probably out of an abundance of caution, but perhaps falling into a bit of the myths.

We did a piece several days ago that busted some of those. There is an abundance of caution. People do wear gloves. When we were in the DEA lab, everyone who was touching even the bags wore gloves. But the cases in which fentanyl by contact has actually poisoned someone are really nonexistent, according to the experts we’ve talked to.

So someone purchasing a pill on the illicit market often doesn’t know what they’re ingesting is what it sounds like is happening.

Absolutely. You’ve got two crises out there, as we like to say.

There’s this one, which is people who are seeking out fentanyl as their drug of choice and eventually, in many cases, they overdose because of it’s potency – because they you never know quite how much fentanyl is going to be in one pill.

But there’s an equal crisis out there, and those are the people who aren’t looking for fentanyl – they may be looking for a Percocet – and they are poisoned by a pill that’s disguised to look like something else.

Traditionally, stereotypes about drug abuse often drag down discussions about what’s happening in the real world. It’s interesting that you’re taking on these stereotypes in this series, but could you tell us more about the story of Jacob Brodsky?

Yes, Jacob was a freshman at St. Edward’s in Austin. His parents spoke to us in just an awful and unvarnished candor about his death.

He died two years ago. He was having trouble sleeping. He was taking some medication for some dental surgery that was keeping him awake. He bought a pill on social media from someone who had photos that made it look just like a Percocet. He took it. He was going through his evening routine. He had gotten into his PJs, was headed toward his bed, and he dropped dead before he ever got to his bed.

» RELATED: Texas teachers could be trained to administer opioid overdose-reversing drugs like Narcan

Why did your team decide that you wanted to take on this topic? What was it that sparked you to devote an entire month to fentanyl?

Back in February, I broke a story about fentanyl killing three middle school students and seven others hospitalized in a North Texas suburb. And from our reporting, it became clear that these kids who had been experimenting with this drug, they had no idea it was actually fentanyl.

So we were continuing to cover the many federal arrests that were coming out of what was, in effect, one single drug house. And our executive editor, Katrice Hardy, challenged some of us to go deeper on what was happening – deeper than what was just happening in Carrollton. And that’s what we spent the summer doing.

The reason that we timed it the way we did it was we believe strongly that there is no more important conversation for parents to have with kids right now than the one about fentanyl.

Well, what else should people know about fentanyl? Like where to get help? Is that information readily available?

A good place to start would be a toolbox we’ve created online. It has everything in it from a Spanish translation of our entire project to help parents can better educate their kids, where people can find help if they face addiction. And the best place to get that through our paper is dallasnews.com/deadlyfake.