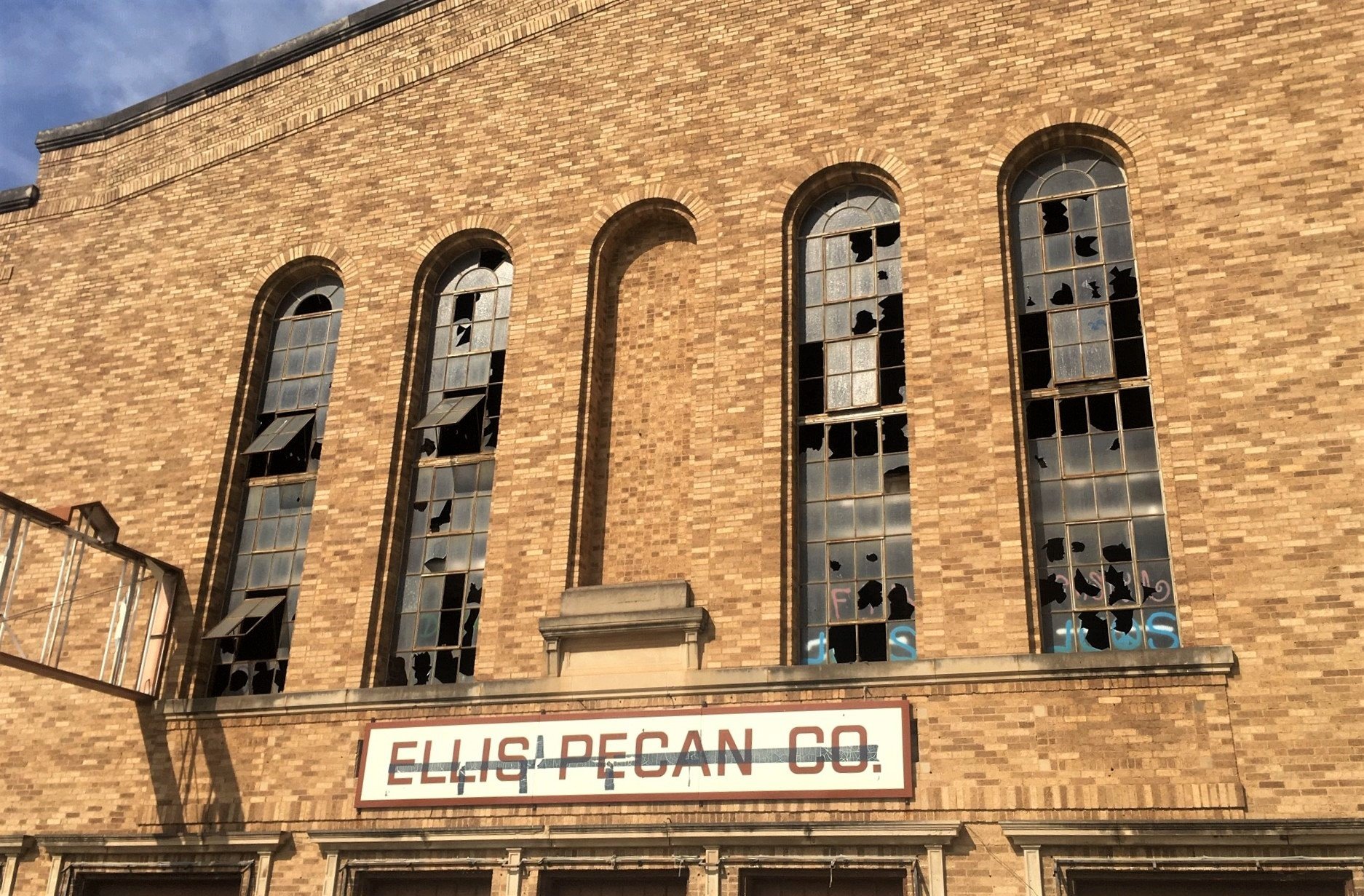

The recently announced plan to re-purpose the old Ku Klux Klan hall on Fort Worth’s Northside has been budgeted at $40 million. The aim is to turn it into a “cultural hub” unlike a typical community center or history museum.

That’s because the hulking, red-brick building has been an embodiment of hatred and fear since Texas Ku Klux Klan Klavern #101 put it up in 1924. Its purchase by a collective of eight North Texas non-profit groups is the start of the hall’s conversion into a center that’ll give back to the same communities the Klan targeted: Black, Latino, immigrant, LGBTQ. The aim is “reparative justice.”

Daniel Banks is chair of Transform 1012 North Main Street — the collective that worked for two years to purchase the hall. He says their ideas for the project evolved. They initially thought they would include a history museum, for example. But they dropped that because the National Juneteenth Museum will be built in Fort Worth. There’s also a new African-American museum and cultural center being developed in town.

“When we got together with some of the other projects and realized what they’re going to do,” Banks said, “we knew we didn’t need to fill that role.”

The building’s now The Fred Rouse Center for the Arts and Community Healing. Rouse was a Black butcher who was lynched in Fort Worth in 1921.

The new center will, in fact, contain a performance space – like most cultural centers – as well as meeting rooms for coalition groups, including SOL Ballet Folklorico, The Welman Project (specialists in re-use) and the Tarrant County Coalition for Peace and Justice.

But the collective also plans to offer a safe space for LGBTQ youth. It’ll establish a tool library for DIY classes, an artisan marketplace, affordable live/work spaces for artists-in-residence, a farmers’ market – and more.

That sounds like a lot of activities going on in a single building. But the Klan auditorium is cavernous. It’s believed it once held seats for 2,000 people. The building is approximately three stories tall and covers 22,000 square feet. The entire plot of land it stands on is 1.3 acres.

Said Banks: “We’ve already had some organizations ask us when the building will be open that they can rent out for their own uses. “

The current timeline has the Fred Rouse Center opening in three years. The building is in poor shape. Parts of the rusted roof have collapsed with pieces littering the floor. Wooden stairs have deteriorated. The hall needs to be stabilized first.

To purchase the hall and get started upgrading and adapting it, Transform 1012 has already received funding from a range of sources, including Atmos Energy, the Rainwater Charitable Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts.

But Banks said, one outstanding feature of the center is not just what it aims to do. It’s the way this project of adaptive re-use is being created and run. There aren’t many cultural centers that have been established by a coalition of non-profit groups that set out to buy, transform and program a building with this kind of history.

“We created this model ourselves,” said Banks. “Because we wanted to be a model of what this would look like for others.”

One member of Transform 1012 is the Opal Lee Foundation. The 95-year-old Lee is known as the “grandmother of Juneteenth” because, as a Black activist, she led the successful push to establish that day as a national holiday, celebrating African-Americans’ freedom from slavery.

“Lord knows we go through enough obstacles just trying to live,” Lee said. “Here, with a building that was used for evil, we can turn it into something that’s extremely good.”

Opal Lee is ready for her foundation to use this former Ku Klux Klan hall — to hold its own board meetings.