Texas has long had a love affair with country music. But the genre is changing, and in ways many might not fully appreciate.

Of the 149 members of the Country Music Hall of Fame, only three inductees are Black – none of them Black women. But after years of whitewashing, there may be a big reason the country music industry is finally having a reckoning as a new generation of Black country artists and fans are bringing in a fresh dimension of sound and social consciousness.

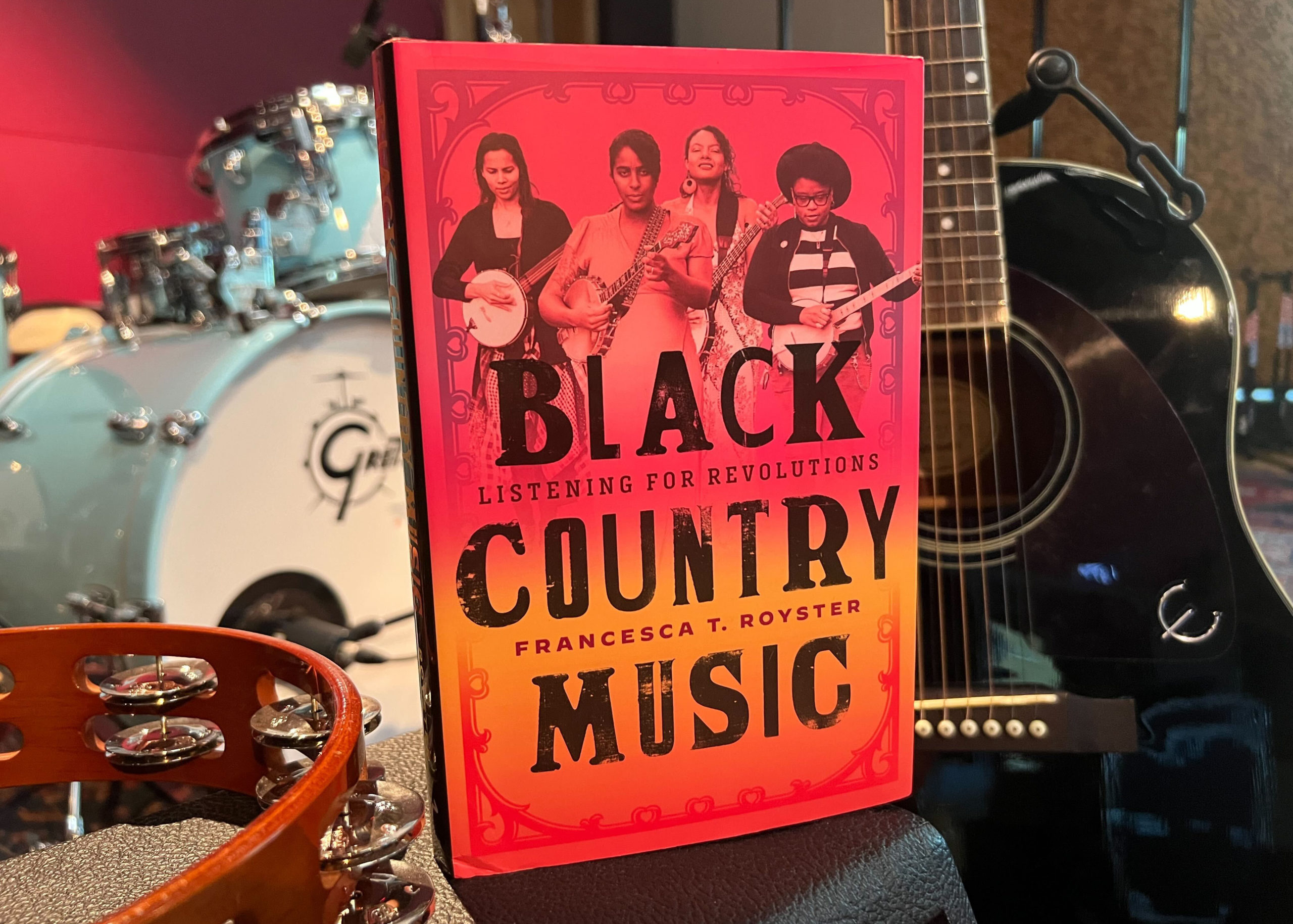

Author Francesca Royster, a professor of English at DePaul University, talked with the Texas Standard about this change and its importance in her new book “Black Country Music: Listening for Revolutions.” One main point: The definition of country music is vast, ever-expanding and rooted in Blackness.

She included a list of a few of her favorite songs in this special playlist on Spotify: