From KERA:

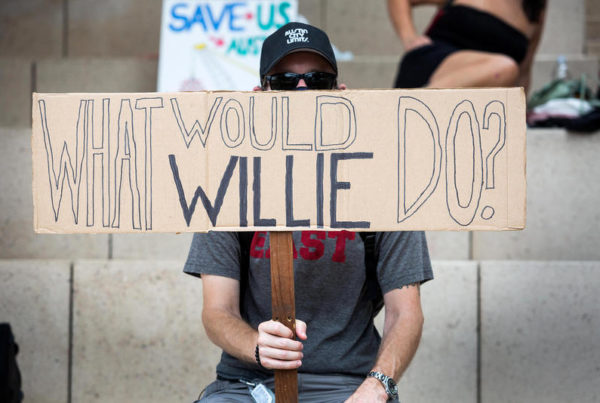

On a cloudy Thursday, as shoppers bustled in and out of an El Rancho grocery store in Fort Worth, a half dozen activists stood at the entrances, offering voter registration forms.

Yadira Avitia signed up one person that evening.

“She said she hasn’t been registered for a while and we just helped her fill out the application,” Avitia said.

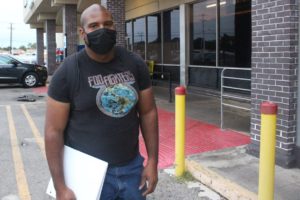

Avitia is a volunteer deputy registrar, which means she’s legally allowed to help register people in Tarrant County. Her colleague Dequan Johnson worked the other entrance, asking people if they’re registered.

He said he does the same thing at protests.

Dequan Johnson.

“That’s how I can be that much more a part of a movement,” he said. “I see you protesting and that’s fine, but are you going to vote? We need that.”

Protests over the summer after the killing of George Floyd brought thousands into the North Texas streets, many who are new to civic action. But it’s unclear how much of that energy will show up during early voting, which starts Oct. 13, or on Election DayNov. 3.

Johnson and Avitia are part of the group Enough is Enough Fort Worth. Co-founder Kwame Osei Jr. said they’ve broadened beyond the protests in order to turn people out.

“As we were going to protests, we started going to more City Hall meetings and meeting with the chief of police and meeting with [Fort Worth] Mayor Betsy Price,” Osei Jr. said. “That’s where we started to shift the focus to a more community base. Because if we don’t change anything in legislation, then nothing’s going to happen.”

‘Grassroots Is The Way To Go’

Organizations like this one want to reform how cities, states and the federal government spend tax dollars and govern policing. That takes influencing elected officials or electing new ones.

Many of the summer’s protesters were teenagers, though, taking civic action for the first time. The voting habit doesn’t happen automatically.

Democrat Jasmine Crockett, who won her July primary runoff for Texas State House by less than 100 votes, said political candidates have to “do our part.”

Crockett said her campaign registered hundreds of people it met at Dallas protests. Her district is largely within the City of Dallas and she has no opponent in the general election.

“Grassroots is the way to go, no matter what, especially when you’re talking about the younger voter or the voter who’s normally disengaged,” she said. “For them, they’re looking at it and they’re saying, I see [the] president, but I don’t see the rest of you. And so you’ve got to make it to them, some way, somehow.”

That could take dropping off fliers at a voter’s doorstep, something Crockett considers a key tactic. Ultimately, it’s the relationship a candidate forms with a potential voter that turns them out, she said. And since people don’t necessarily know what a state representative does, or what role that person plays in setting policy, Crockett said candidates have to inform them.

‘Protest To Power Building’

Daniel Rentie said people are still learning about how local government works. He works in Frisco First Baptist Church’s college ministry and volunteered to help organize a protest in the city on June 1. Thousands turned out.

Now, Rentie is thinking about how to keep the momentum going and helping with a local voter registration drive.

“I haven’t been the most involved on the state level, you know what I mean? It gets often neglected,” he said. “And that’s where it’s shifting my attention too, is how we can — locally — get more involved.”

One group that’s been organizing on the ground for years is the Texas Organizing Project, or TOP. Deputy Director Brianna Brown said her staff and volunteers tried to have meaningful, yet socially-distant conversations with protesters this summer.

Brown’s group made about 1,200 new contacts across the state during the recent protests, about a third of which were in Dallas. Of that third, 80 attended a follow-up virtual meeting. TOP’s work with these new Dallas activists is centered around policy issues, like the city’s police budget.

Converting those people into voters, however, is not their number one priority.

“More critical for us is, how do we figure out real and meaningful ways for people to be engaged beyond the election?” she said.

Separately, the group plans to contact over 1.5 million voters this fall, mostly people of color.

“Protest to power building is what organizing [is] all about,” Brown said.

And while voter registration is sharply down this year due to the pandemic, there is evidence protests have increased voter turnout in the past among some voters.

“For example, although Black voters cast ballots in lower numbers in the 2016 general election than they had in 2012, the drop off was less pronounced in areas where Black Lives Matter was active,” University of Pennsylvania professor Daniel Q. Gillion wrote in a recent piece in The Atlantic. “And in areas that witnessed heightened levels of protest activity, Black voter turnout increased.”

The Enough is Enough Fort Worth activists are not leaving that to chance. They plan to visit busy locations in areas of Fort Worth a couple of times a week until the Oct. 5 voter registration deadline. Their focus is on neighborhoods with high numbers of low income people and people of color.

And though interactions with potential voters at the El Rancho that day were fleeting, Osei Jr. said deep conversations do happen.

When he meets a person who says his or her vote doesn’t matter, Osei Jr. said he calls on an analogy.

“I say, say … you have a sibling. And that sibling is putting 5 cents a day in their piggy bank. And you’re not putting nothing into your piggy bank. Who’s going to have more money?”

He means saving money over time is like consistent voting, where you build up political influence. It’s by voting, he said, activists can get closer to results they want.