The U.S. Justice Department is suing Galveston County over its recent redistricting plan, which would eliminate the county’s sole majority-minority precinct. It’s not the first time the federal government has intervened with the county’s redistricting plans.

But federal law has changed dramatically since the last time Washington stepped in, and the Galveston case could be a stress test for the weakened Voting Rights Act.

The 2013 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in the case of Shelby County v. Holder neutered Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, which required historically segregated jurisdictions to get federal preclearance before changing their voting maps. Last year marked the first round of redistricting since that time.

“Without the preclearance component, I think things like this could potentially go on all over the country, and certainly we are a jurisdiction that it obviously happened to us,” said Stephen Holmes, Galveston County Commissioner for Precinct 3.

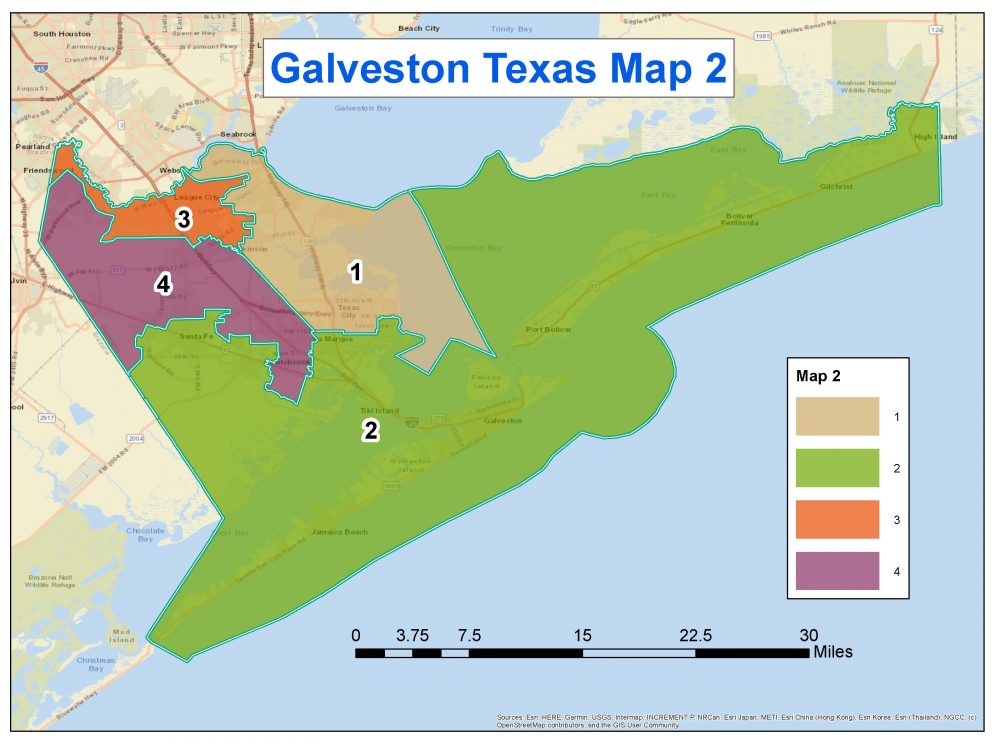

For decades, Precinct 3 was the sole majority-minority precinct in Galveston County. It’s now the sole Democratic precinct as well. But the new map radically redrew its territory, pushing it inland and dividing up the county’s Black and Hispanic communities among the other three precincts – diluting their voting power, a process known informally as “cracking.”

ed by Republican County Commissioner Joe Giusti.

“I was, like, in shock. How are you going to do something and you haven’t gotten the public’s opinion about it?” Christian said. “You’ve already made a decision, and they had already showed it in the paper the way it was going to go without anybody knowing anything.”

The vast majority of the public speakers opposed the new map, asking County Judge Mark Henry and the other Republicans on the court to scrap it and adopt boundaries closer to those already in place.

It had no effect. The commissioners passed the map on a 4-1 party line vote.

Henry did not respond to multiple interview requests for this story.

Holmes is next up for reelection in 2024, and he will almost certainly lose his seat if the new map is allowed to stand.

“I don’t have concerns for myself in my reelection,” Holmes said. “I don’t have any concerns for that at all. My concerns are for the community in and of itself to have their voting rights restored in time for the next election.”

The Justice Department filed its lawsuit against Galveston County and Judge Henry in late March, invoking Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Section 2 bars states and localities from intentionally discriminating against minority voters in redistricting.

“Our complaint alleges that Galveston County has violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act by devising a redistricting plan that dismantles the only district in which Black and Hispanic voters had the opportunity to elect a candidate of choice to the county’s governing body,” said Kristin Clarke, assistant attorney general for the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division in a press release announcing the lawsuit. “We will continue to use all available tools to challenge voting discrimination in our country.”

Holmes has represented Precinct 3 since 1999, when he was chosen to replace the county’s first Black commissioner, Wayne Johnson. He sees the brewing conflict, and the federal lawsuit, as a 1960s style fight for democracy.

“Normally they’re suing a large entity like a state, many states based on their redistricting practices,” Holmes said. “So for them to come in and sue Galveston County I think speaks to the level of the discrimination that was created in this map.”

Before the Supreme Court did away with preclearance, the Justice Department stepped in to block changes to Galveston County maps twice – once in 1992 and again in 2012. Retired attorney Anthony Griffin helped lead the 1992 fight at the request of the late Commissioner Wayne Johnson.

“We made a decision to bring lawsuits against practically every jurisdiction in Galveston County to at least give African American officeholders a chance to be elected,” Griffin said of the suit. The George H.W. Bush administration’s Justice Department responded with a Section 5 objection, overturning the county-proposed maps for justices of the peace and constables.

“Galveston County was one of the first cases that (was) brought, and then it was the City of Galveston, and then we went to Galveston College Board, the city of Texas City, the city of La Marque. And they were pretty effective in terms of doing so,” Griffin said.

The Republican majority on Galveston County’s Commissioners Court tried a more extensive redrawing of the maps in 2011, this time targeting Holmes’ Precinct 3 as well as the justices of the peace and constables. The Obama administration’s Justice Department filed a Section 5 objection March 2012.

But with Section 5 gutted, the federal government must rely on Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act as a remedy. With Section 2, the outcome is far less certain, said Charles “Rocky” Rhodes, a constitutional law professor at South Texas College of Law Houston.

“Section 2 is not as efficient because it requires the Department of Justice or individual citizens to sue after the change has been made to try to later invalidate the change, and then that process can take a long time,” Rhodes said. “Whereas under Section 5 the change could not go into effect until it had either been precleared by the Department of Justice or a court had agreed that it did not have the purpose or effect of diluting minority voting rights.”

Retired attorney Anthony Griffin said, nevertheless, he’s encouraged that the Biden administration chose to file a Section 2 lawsuit.

“I still think you can win,” Griffin said. “I think you can still show an effect of discrimination, and I believe that the elected officials essentially have misread Section 5, and they misread the Supreme Court. I think at some point you go too far.”

Not everyone is convinced, however. David Miller, for one, is skeptical. A former president of the Galveston NAACP, Miller says Section 2 is only as strong as the courts allow it to be.

“Unless you get a favorable judge that would adhere to the law and not to political views, it ain’t going to do nothing,” Miller said. “You have to get a judge (who) obeys the law and sticks to the law. So, unless we get this in front of the right judge, who’s going to make a decision based on the law and not on what’s popular to another party, we’re still going to be in trouble.”

Miller has legitimate cause for concern: The U.S. Supreme Court has been sending signals that it plans to revisit Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Two months ago, the court stayed a lower court ruling against Alabama over new congressional maps that got rid of a heavily black district. The vote in that case was 5-4, with Chief Justice John Roberts voting with the court’s liberal minority.

“It was a very radical decision,” said Daniel Morales, an associate professor at the University of Houston School of Law. “They signaled their willingness to upend the precedents that allowed the creation of these districts that ensured a minority voter representation under Section 2, and sort of noted that they were interested in Alabama’s theory that would require non-race-conscious district drawing, which is antithetical to the Voting Rights Act.”

Morales said the Alabama case and the Galveston County case are very different, because only the latter involves an allegation of intentional discrimination in the drawing of maps. The High Court won’t rule on the Alabama case, Merrill v. Milligan, until 2023, after the next congressional election. It’s impossible to tell how the court’s ruling on Section 2 in that case will affect how the provision can be applied in the Galveston County case, but the consequences for Galveston County — and the country — could be sweeping.

“The court is signaling that it might interpret Section 2 in a way that would really render it toothless as well,” Morales said. “Which basically means that our experiment in multiracial democracy may fast be coming to a close.”