From Houston Public Media:

Bo Svensson moved to his home in Northwest Harris County’s Cypress area a couple of years ago. He liked the neighborhood’s tall shady trees and big lots.

“I wanted a better quality of life for myself and my wife and two daughters,” he said.

His house is on well water, which was presented as a benefit at the time. “I was told that the well water was really, really high-quality water,” he said.

So Svensson said he was shocked to learn there was a toxic site nearby – and that it was still contaminating some private well water.

“Apparently, a lot of the other neighbors that have been here a long time had heard about it – it was all news to me,” he said. “I don’t want to get sick and so if there’s any issue with it I have to do what’s best for my family.”

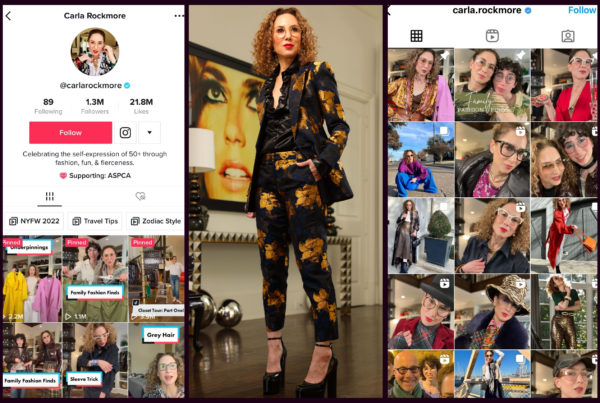

Bo Svensson talks to HPM reporter Katie Watkins. He says he moved into his home with his wife and two daughters a few years back. He agreed to have his well water tested for chemicals after learning about the nearby Superfund site.

Courtesy of THEA

The site near Svensson is the Jones Road Superfund site. Superfund sites are contaminated areas targeted for cleanup through the federal Superfund program. The Jones Road Superfund site is located in a strip mall where the now-closed Bell Dry Cleaners operated for nearly 20 years. The former dry cleaners failed to properly dispose of its hazardous chemicals, and they seeped into the soil and groundwater.

Specifically, they used tetrachloroethylene (PCE) as a dry cleaning solvent, which is itself a likely human carcinogen. PCE also breaks down into other toxic chemicals of concern, including TCE, DCE, and vinyl chloride. Nationally at least 10 Superfund sites in states like Florida, New Jersey, and Nebraska were former dry cleaners.

Once in the ground, dry cleaning solvents can contaminate the soil and groundwater for tens to hundreds of years and cleanup can be both long and costly, according to the EPA. Vapor from the solvents can also enter nearby buildings.

The Jones Road Superfund Site is located in a strip mall where the former Bell Dry Cleaners operated for nearly 20 years.

Katie Watkins / Houston Public Media

The EPA embarked on a plan to clean up the Jones Road Superfund site just over a decade ago. Part of that includes removing chemicals from the groundwater and soil and continuing to test private wells while connecting residents to a safe public water source.

But despite years of remediation, a recent report from the federal agency found that it’s still not protective of human health and the environment.

In particular, the report outlines concerns that some residents using private wells may still be exposed to contamination. Roughly one-fifth of the private wells the EPA recently tested had levels of chemicals that are not safe for consumption.

Jones Road Superfund site.

Via EPA Report

Svensson is outside of the EPA’s official well-testing area. But there are some concerns from residents and environmental groups that the contamination may have shifted since the EPA first determined the plume’s boundaries.

“I mean, do I believe it’s migrated this far?” Svensson said. “I doubt it, but I don’t know.”

One of the organizations that is pushing for more testing and information is the Texas Health and Environment Alliance, or THEA. They’ve teamed up with researchers from the University of Texas Medical Branch, UTMB, to test the water and air at 55 properties – both inside and outside the EPA’s official boundaries.

Lance Hallberg with UTMB said the goal is to have data for the community.

“The purpose of whatever we find whether good or bad is for them to be able to utilize that in requesting any additional services from EPA if necessary,” he said.

Back in 2008, the EPA footed the bill to connect affected residents to the municipal waterline and plug their wells. But roughly half the residents did not take them up on the offer.

Lance Hallberg, a researcher with UTMB, takes a water sample from a private well near the Jones Road Superfund site.

Courtesy of THEA

Raji Josiam, the site manager with the EPA, said that’s what’s causing some of the continued problems with the groundwater contamination today.

“They have been continuing to use their well water and as a result, that’s been pulling the plume from underneath the source area at the Superfund site to the residential area,” said Josiam.

For now, she said the EPA doesn’t plan to expand the boundaries of where they do well testing.

“If we have a reason to believe that we need to step out, we definitely will do that,” she said. “But right now, based on all the data, we are seeing the contamination itself is much closer to the site.”

Josiam said outreach efforts to connect the remaining residents to the public water line stalled during the pandemic, but they’re making another push to connect residents to public water this year, using funds from the bipartisan infrastructure act. It’s one of dozens of sites nationwide to receive funding in an effort to reduce the cleanup backlog.

The EPA plans to hold a public meeting in February to update residents on the site and to finalize the list of people who want to connect to the public water line, according to Josiam.

Though well contamination is still an issue, Josiam said the EPA has made progress in removing the source of the contamination through a process called soil vapor extraction.

“The one thing that we are seeing is the remediation of the source area itself,” she said. “We have definitely reduced the contamination that’s going into the underlying groundwater.”

Marc Musters has lived in his home in Northwest Harris County for more than 40 years. He’s had his well tested repeatedly for chemicals associated with the Superfund site.

Katie Watkins / Houston Public Media

Even so, some longtime residents feel the process has been dragging on. Marc Musters has lived in the area for more than 40 years – he moved in even before the dry cleaners started operating.

“They told us at that time, this was back in the early 2000s, that it would take 20 to 25 years to clean up, and we’re all going looking at each other, going ‘you got to be nuts,'” he said. “You know what the problem is, you know, where the problem is.”

Musters has had his well tested repeatedly. So far, it’s continuously come back clean. But he said until the contamination is gone he’ll continue to get it tested to keep track. He feels like over the years communication about the site has dwindled.

“It’s like they’re trying to drag it out long enough, so people will forget about it,” he said.