From KUT:

When junior Ryan Weeks heard a student from Hays CISD had died from fentanyl poisoning last summer, he thought it would be a one-time thing.

It wasn’t.

He found out a classmate at Lehman High School had died from a fentanyl overdose right before the beginning of the school year.

“I used to say ‘hi’ to him, might even play video games from time to time,” Weeks said. “And then, just like that, he’s gone.”

At first, Weeks said, it didn’t hit him that his classmate wasn’t coming back.

“But once it actually hit me, I was like dang … it’s for real, it’s serious,” he said.

Lehman High Junior Ryan Weeks said it took him a while to realize a classmate who overdosed really wasn’t coming back to school. “But once it actually hit me, I was like dang,” he said. “It’s for real, it’s serious.”

Patricia Lim / KUT

There have been six fentanyl overdose deaths at Hays CISD since last summer. Fatal overdoses among those under 18 more than doubled between 2019 and 2021. The crisis has prompted the district to launch a campaign to educate the community about the dangers of fentanyl and hopefully prevent more deaths.

Weeks and his classmate, Alyssa Jones, are on the Hays Student Advisory Council and have spoken with the school district, local officials and lawmakers about what’s been going on in the district.

“[It] was the first time that I realized that it was not a single student, but that it was affecting our community as a whole,” Jones said.

Nurses come running

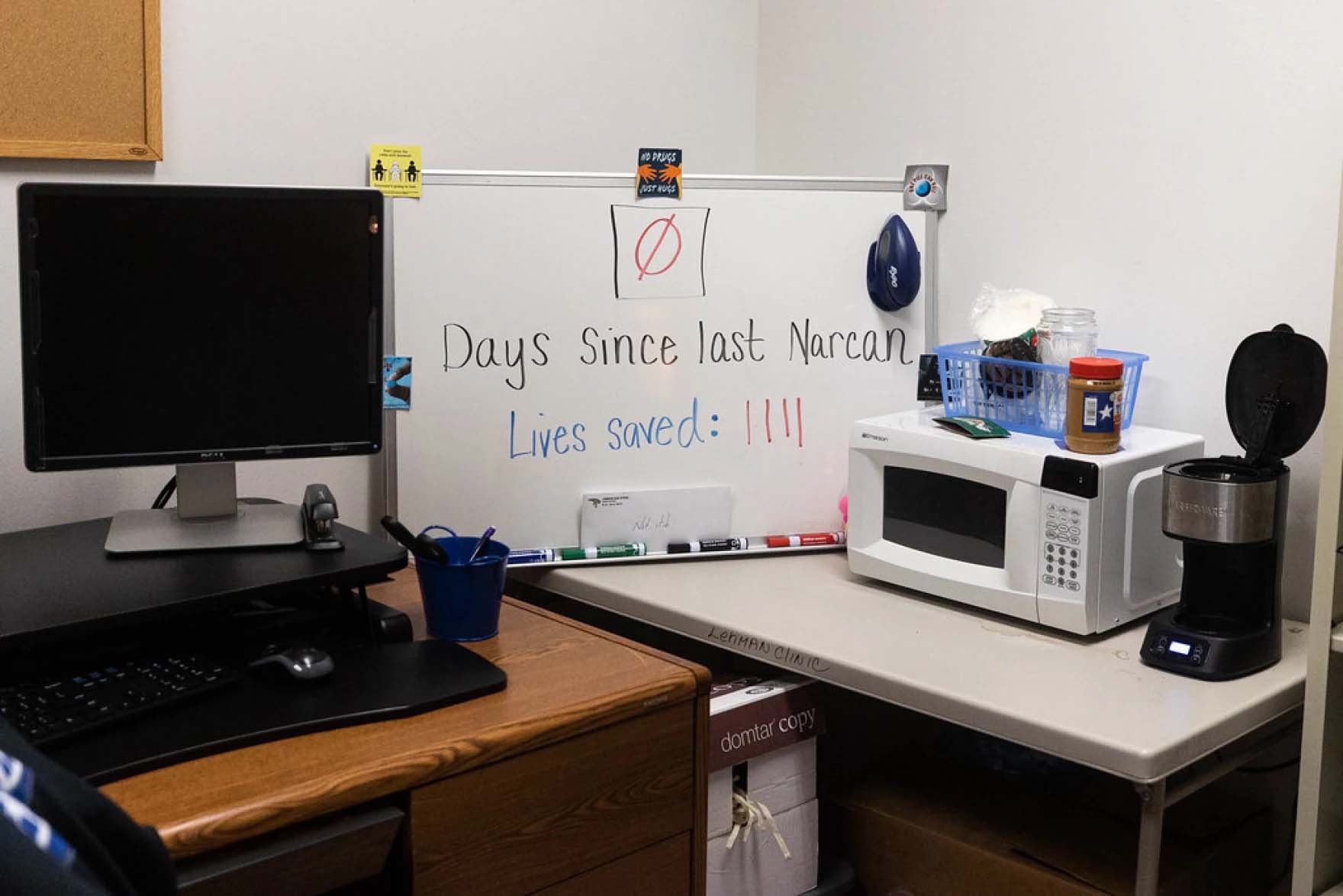

At Lehman, there are supplies of Narcan, a drug that reverses overdoses, at the nurse’s office and on the other side of the school, near sports facilities.

School nurse Elainna DeWitt said administrators have radios and will coordinate where they need to be in an emergency and who can respond faster. Unfortunately, she said, staff have had to use the protocol several times this school year: Urgent voices talk over the radios, the school goes on lockdown, and nurses come running with an emergency bag and Narcan.

“We get there, in all the instances, [and] the students have been blue,” DeWitt said.

The student produces a deep snoring sound, she said, as they desperately try to breathe. “It’s their body trying to get any type of oxygen to their brain … they’re fighting death at that point.”

Nurses at Lehman High School have administered Narcan to students multiple times.

“I never expected in my life to have to give Narcan in a school setting when I decided to become a school nurse,” DeWitt said.

She said she believes this isn’t just happening in Hays CISD; the district is just making the most noise.

Lehman High School nurses Christina Fehler and Elainna DeWitt have had to administer Narcan multiple times to students overdosing this school year.

Patricia Lim / KUT

No standardized tracking

Tim Savoy, chief communications officer for Hays CISD, said although there have been six student deaths in the district, another 22 student overdoses weren’t fatal.

“The deaths are horrible, they’re shocking and very scary,” he said. “But when you add in the number of overdoses that we know about … it brings home how big the problem really is.”

It’s up to individual school districts to keep track of student deaths and overdoses, which Savoy believes is a huge problem. Districts that choose to dedicate resources to collecting data struggle to get real numbers. Certain factors can complicate things: whether an overdose happened on or off campus, if EMS or police have a record of the incident, or if Narcan was used outside of school.

With so many variables, Savoy said, there’s no way to know if Hays CISD is actually a hot spot or if other districts are just tracking differently and aren’t aware of a problem.

San Marcos CISD and Dripping Springs ISD, for example, haven’t reported any fentanyl-related student deaths or overdoses this year. Officials also say they haven’t had to use Narcan.

If districts were given the same set of guidelines and one place to keep all this information, Savoy said, schools in need could ask for funding to expand mental health and counseling services to help kids struggling with addiction or grieving the loss of friends.

“I think you also need [accurate data] so that policymakers at all levels of government — whether it be local, school district, state or federal — understand the magnitude of the problem,” he said. “So that they can properly resource solutions.”

Savoy said Hays CISD has a good relationship with local law enforcement and emergency services. He adds information he learns into a chart he keeps in a Word document.

“I know that each district is different,” he said. “Other districts are taking different approaches and they may or may not have relationships [with EMS and law enforcement]. And it gets muddy.”

‘A human being behind those numbers’

In March, a bipartisan group of Texas lawmakers requested the Texas Education Agency respond to concerns raised by parents and community members about the presence of fentanyl in schools.

The TEA said it developed a communications toolkit inspired by Gov. Greg Abbott’s $10 million One Pill Kills campaign. The toolkit includes webinars, training for district staff and a statewide resource page for school districts to use as they see fit.

The agency told KUT it does not track fentanyl-related student deaths — or student deaths, in general. It did not provide comment on whether it will create a system to standardize data collection.

But collecting data isn’t the only thing districts need.

“You have somebody in crisis, you have somebody with an addiction,” Savoy said. “You have a human being behind those numbers, and I think that’s critical to remember.”

Lehman High student Alyssa Jones, a member of the Hays Student Advisory Council, wants to bring awareness to the fentanyl crisis.

Patricia Lim / KUT

Jones said kids could have many reasons for doing drugs.

“I think that a lot of the time, whenever people see a news story about a high school student overdosing, they assume that the student wants to be cool or maybe that it’s their choice,” she said. “But a lot of the time what we’re seeing in our community is children who are addicted to these drugs.”

By advocating for expanded mental health resources and rehabilitation programs, Jones said she hopes she’ll be able to bring more awareness to the issue.

“Drugs are dangerous like they never were before,” she said.