From Houston Public Media:

Marty Lancton has responded to countless calls in his 25 years as a firefighter, but there’s one call that has stuck with him over the years.

He remembers not knowing much about the situation on the way to the scene — all he knew was that someone needed help.

“We pulled up to the house and the mother came out and dropped her lifeless baby in my arms,” Lancton recalled.

This happened 15 years ago and he said he still thinks about it nearly every time he dresses for work or hops on a firetruck. His nieces and nephews were young at the time, making the details all more emotional for him.

“I can remember having to begin to do CPR, putting a tube down their throat and starting IVs,” Lancton said. “We did everything humanly possible to save this baby’s life.”

But the baby had already died. Lancton said these situations often lead firefighters to question whether they did enough — and those questions can linger for years.

“These calls, they stick with you,” said Lancton, president of the Houston Professional Fire Fighters Association, the department’s union. “It’s never left my mind, and those stories, you could go to any firehouse in Houston and there’s going to be thousands of these stories.”

Being a firefighter is not only a physical commitment. Some say the mental toll is heavier.

Marty Lancton is president of the Houston Professional Fire Fighters Association, the union for the Houston Fire Department.

Colleen DeGuzman / Houston Public Media

They respond to dozens of calls for help each shift, sometimes working multiple 24-hour shifts a week. That’s why Lancton said its in-house team of therapists is a key part of seeing Houston Fire Department’s firefighters through the traumas of the job.

“They’re expected to go out there on people’s worst day, see the worst tragedies of peoples’ and families’ worst days, mitigate that, take care of people, try to save their lives, then go back to the station,” Lancton said. “And then they do that about 15 or 25 times a day.”

On top of the stressful nature of their job, Lancton said “it has been an incredibly emotional year” for Houston firefighters. In 2024, the department received a long-awaited workers contract after a nearly decade-long, bitter dispute with the city.

They also grappled with the death of one of their own, Marcel Garcia, who died in November after a wall collapsed on him at a warehouse fire in Houston’s East End.

Houston firefighter Marcelo Garcia died Nov. 6, 2024, after responding to a fire in the East End.

Houston Fire Department

“Typically, with the line of duty death, we get calls about survivor’s guilt. They ask, ‘Why not me? That could have been me, I was so close to it,'” said Leah Belsches, one of two clinical psychologists for the department.

She offers one-on-one sessions for firefighters and their family members, along with peer-support groups that she facilitates. “The amount of emotion and guilt that follows to say, ‘Did I do enough? Did I do a good job?’ are really, really complex emotions, so we help them process through that,” she said.

Lancton said firefighters close to Garcia have participated in several peer groups following the death of Garcia “to show that when the lights are gone and the funeral is done, that doesn’t mean the pain goes away – and most importantly, that we’re still going to be here.”

Just as heat-proof coats and hard-shell helmets are essential for a firefighter’s safety, Belsches said her team is as important because the mental health risks of being a firefighter may be the most dangerous part of the job.

Firefighters are three times more likely to die by suicide than to die in the line of duty, according to the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation. Locally, among Houston’s 3,600 firefighters, Belsches said around 300 contacted her department this year.

She boils her job down to simple terms: “It’s to be there for our firefighters. That phone you see right there, someone is always going to pick it up.”

“When they initially come in, it’s depression, it’s PTSD, it’s anxiety,” she added. “But the more we start talking, we find out that you’ve been having some suicidal thoughts as well.”

Belsches estimates that a quarter of the firefighters she saw this year struggle with suicidal ideation, and even then, “it’s probably much higher than what our firefighters are sharing with us or open to sharing.'”

Leah Belsches is one of two clinical psychologists for the Houston Fire Department.

Colleen DeGuzman / Houston Public Media

She added that sometimes, firefighters aren’t prepared for the mental health risks of the job.

“Sometimes folks leave the academy and they’re prepared to be a firefighter but they’re not prepared for the amount of trauma that they might encounter,” she said, “the bodies they might see, the gore that they might see that no human is really meant to see and no brain is meant to truly process.”

The number of firefighters reaching out to their in-house mental health services is low compared to how frequently officers with the Houston Police Department reach out to their clinical psychologists. Among the police department’s 5,200 officers, around 500 of them contact mental health resources every month.

The police department’s mental health team is also several times bigger than the fire department’s. They have eight licensed psychologists with plans to grow to nine next year.

Belsches said she hopes that in 2025, the number of firefighters reaching out to her department doubles. Firefighters don’t often reach out for help when they need it, she added, because “there’s still that myth of, ‘If I talk about this I might lose my job.'”

That stigma is dangerous because it can cause mental health issues to worsen over time for first responders.

Lancton, however, emphasized that he not only hopes to encourage firefighters to be more open about their mental health, he wants it to be a normal practice among team members.

“When they need help, we need for this to not be a secret, we need this to not be something that we don’t talk about,” he said.

This is more critical for Houston’s firefighters because the risks of the job to their mental health is compounded by a list of other long-standing problems.

Lancton says the department has been critically understaffed for years. They’re down about 600 firefighters than the team should be at, considering the number of calls they take and how big the city’s population is.

Serving on an understaffed team in one of the nation’s most populated cities can lead to higher rates of stress, Belsches says.

“It’s left our firefighters burnt out, exhausted, working overtime, being held over, which has all the more contributed to mental health issues,” she said.

The Houston Fire Department has around 3,600 firefighters and two in-house therapists.

Firefighters left by the droves while the department spent nearly a decade fighting for a union contract with the city. A long-awaited settlement was finally approved by Houston City Council last summer, but it left deep scars on the team.

“Pre-settlement morale was low,” Belsches recalled. “Pre-settlement, there was a lot of frustration, there was a lot of anger, there was a lot of confusion, there was a lot of hopelessness.”

Lancton said the department has been rebuilding morale and recruiting new cadets since the settlement.

He said there are now 270 cadets in the academy compared to years during the contract dispute when “we couldn’t get 75 people to show up for an exam and out of that, we were graduating 20 people.”

He said rebuilding the department is a process that also presents an opportunity to firm up mental health care for firefighters.

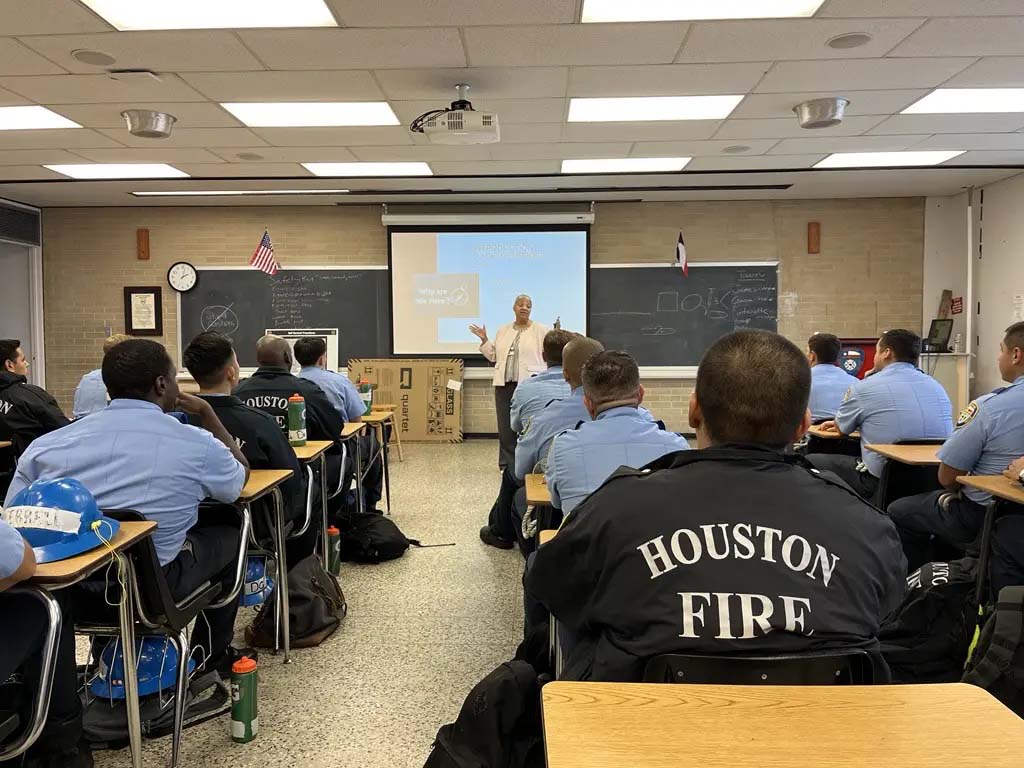

Last year for the first time, firefighter’s cadet training included a course on mental health care, which could become mandatory if funding continues to be available.

Bearing witness to sorrow and pain is inevitable — a firefighter’s job is to rescue people. But Lancton said what is avoidable is letting them believe they’re going through it alone.

Lancton said it’s a step toward making sure the city’s firefighters are better prepared to serve the community. He said he starts and ends every team meeting with this phrase: “If we fail at all else, may God give us the strength and never fail at taking care of each other.”

Houston Fire Department cadets listen as Angelina Hudson, CEO of the National Alliance on Mental Health’s Houston chapter, talks about prioritizing their mental health in the job in September. This was the first time cadets participated in a class on mental health.

Colleen DeGuzman / Houston Public Media