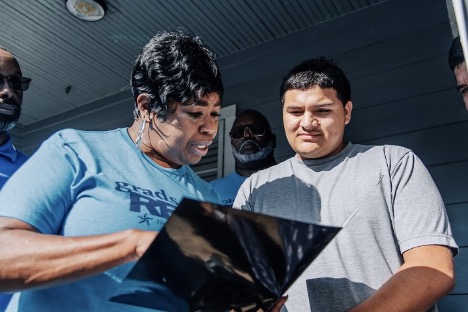

On a warm Saturday morning in mid-September, school counselor Reba Powell knocked on doors in Houston’s Independence Heights Neighborhood. She was part of a group of volunteers, staff members and district leaders encouraging students to re-enroll in high school.

At the home of one student who stopped attending school so he could support his family, Powell told him which courses he needed to complete to earn his diploma in January.

“That sounds good,” he said.

“Okay, let’s do this,” she replied. “We can do this. I know we can.”

He was one of the more than 5,700 students who didn’t return to district high schools at the start of the year, according to HISD.

And it’s not just high schoolers. The largest school district in Texas is getting smaller. Houston ISD’s student body has shrunk by more than 10 percent over the past three years.

Erin Baumgartner is Director of the Houston Education Research Consortium at Rice University.

“We can make very direct connections between COVID and enrollment declines,” she said. “And one of the reasons why we can say that so clearly is when you look at where the enrollment declines were really focused — especially in the 2020-2021 school year — it was really in the earlier grades.”

From the 2019-20 to the 2020-21 school years, HISD’s enrollment declined by about 13,000. More than 10,000 of those students were from elementary schools, according to data HISD reported to the Texas Education Agency.

Baumgartner said it’s too early to be completely sure why enrollment is still dropping at HISD, even as some other large districts are starting to recover.

HISD Executive Officer of Research and Accountability Allison Matney said many of the students leaving the district aren’t necessarily leaving the Houston area.

“We do have families that have moved within the Houston area to another district, whether they’re moving out to a suburb district or they’re moving to live with a family member somewhere else,” she explained. “Again, the charters continue to be a competition … so we’ve got some of that movement as well.”

With about 188,000 students enrolled so far this year, HISD’s student body has shrunk by about 23,000 students since the pandemic began.

The trend erases years of relatively steady growth, even in the face of increasing competition from charter schools. The loss is so severe that the total number of students enrolled so far this year is the lowest since the 1984-85 school year.

The historic enrollment decline has implications for the district’s budget, which is supported by a mix of local, state and federal funds. The State of Texas gives the district a little over $6,000 annually for each enrolled, attending student. The decline in enrollment over the past few years represents more than $130 million in annual base allotments from the state.

“I send out daily enrollment reports, and I know the CFO is probably the first one to open it up,” Matney said. “It’s why we have a multimillion dollar deficit … and that’s something that is of urgency to administration and to our trustees as well.”

For some other big districts in Texas, enrollment declines were already a problem before the pandemic made it worse. Dallas, Austin, San Antonio and El Paso ISDs all saw years of steady enrollment declines get worse after COVID-19 hit.

Some districts have started to bounce back. Based on current enrollment numbers, San Antonio ISD’s student body increased in size for the first time in more than a decade, although it’s still smaller than it was two years ago. Some suburban “destination districts” have already recovered or, like Katy ISD, never even saw an enrollment decline.

Statewide, the total number of students enrolled in Texas public schools decreased by around 122,000 the school year after COVID-19. Statewide enrollment increased last year from 5,371,586 to 5,427,370, but that was still the lowest number since the 2017-18 school year.

“We saw an uptick back, but only in recovery of about half of the student loss that we saw in the year immediately following the onset of COVID,” said Catherine Horn, director of the Education Research Center and the Institute for Educational Policy Research and Evaluation at the University of Houston.

The sharp enrollment declines came as many large districts’ resources were already stretched thin. Horn called the situation “a vicious cycle.”

“You end up having to make choices between untenable options,” she said. “How do you decide whether to have no librarian versus a nurse, or having a larger class size for your kindergarteners?”

The federal government sent money to districts to fill in the gap, but those funds won’t last forever. If enrollment levels don’t bounce back enough, districts will be back to trying to do a lot with even less than they had before. That puts a lot of pressure on districts already facing a history of underinvestment.

And as Erin Baumgartner from Rice University points out, the surge in money wasn’t intended to address those long-standing gaps in public education funding.

“These gaps existed before the pandemic,” she said. “When we’re playing catch up, are we playing catch up to the gaps that existed before the pandemic or are we playing catch up to get everyone to the same playing fields and increase equity and access to opportunities?”

HISD’s door-knocking brought back 67 students in one Saturday, according to the district. For 67 students, that’s a chance to get back on track to earning their high school diplomas. For HISD, it’s a drop in a leaky bucket, representing less than one percent of the total enrollment loss over the past few years.