Hurricane Harvey was a seminal moment in the history of Houston. Five years later, where do things stand? Houston Public Media examines efforts to make the region more resilient to better prepare for the next big storm in Below the Waterlines: Houston After Hurricane Harvey.

How Houston has changed five years after Hurricane Harvey

Five years after Hurricane Harvey, major flood mitigation projects in Houston are still waiting on federal money, in order for construction to begin.

Lucio Vasquez / Houston Public Media

Paula Sitter sits in her new home at 900 Winston. Sitter has lived in three senior living facilities since being displaced after Hurricane Harvey.

From Houston Public Media:

Paula Sitter’s apartment is just a few steps away from the elevator at her current senior living facility, located in the Greater Heights. As you walk towards it, you see fresh paint on the walls, and windows big enough for plenty of natural light to peek through during the day.

Sitter, 76, has lived at 900 Winston for almost two months, after spending seven years at 2100 Memorial. It’s the third public senior living facility in Houston she’s called home, since being displaced after Hurricane Harvey.

“It’s actually better than the others because I’m not heating and cooling as much, which I love,” Sitter says. “I have a big, walk-in closet, and there’s a huge patio.”

More than fifty-five inches of rain accumulated in the lobby of the old 2100 Memorial building during Harvey, a public senior housing facility, and severely damaged electrical equipment. This caused Houston Housing Authority to declare the building unlivable, and issue a five day eviction notice for its senior residents.

Initially, Sitter didn’t want to leave. She never ran out of power, and only two inches of rain had accumulated in her second floor apartment building. Additionally, moving out is especially challenging, since she gets around in a wheelchair, and she is extremely sensitive to the heat, limiting her time outdoors during the day.

While some residents legally fought to stay, Sitter eventually chose to leave after getting a look at the basement.

“I smelled the storage room. All of the stuff for Christmas was in there. It was filled with brown water, feces, we lost everything. That was about 10,000 dollars worth of Christmas stuff.”

Sitter was one of tens of thousands of people forced to leave their homes after Harvey five years ago, and her complex was later demolished due to flood damage on the first floor.

The storm lasted roughly four days, and dumped up to two feet of rain in the first twenty four hours, leaving one third of greater Houston under water. Harvey destroyed over one hundred fifty thousand homes in Harris County, and turned into one of the costliest disasters in US history.

2100 Memorial building endured severe floods during Hurricane Harvey.

Over the past 7 years, not only have Houston and Harris County been recovering from Hurricane Harvey, but from the Memorial day flood in 2015, and again in 2016, with the Tax Day flood. Since then, they’ve been working to make our region more resilient to floods.

“We have been focusing on two aspects of recovery. One is actually the direct damage recovery on the housing side, and then the damage recovery on the public infrastructure side,” says Stephen Costello, Chief Recovery Officer, City of Houston.

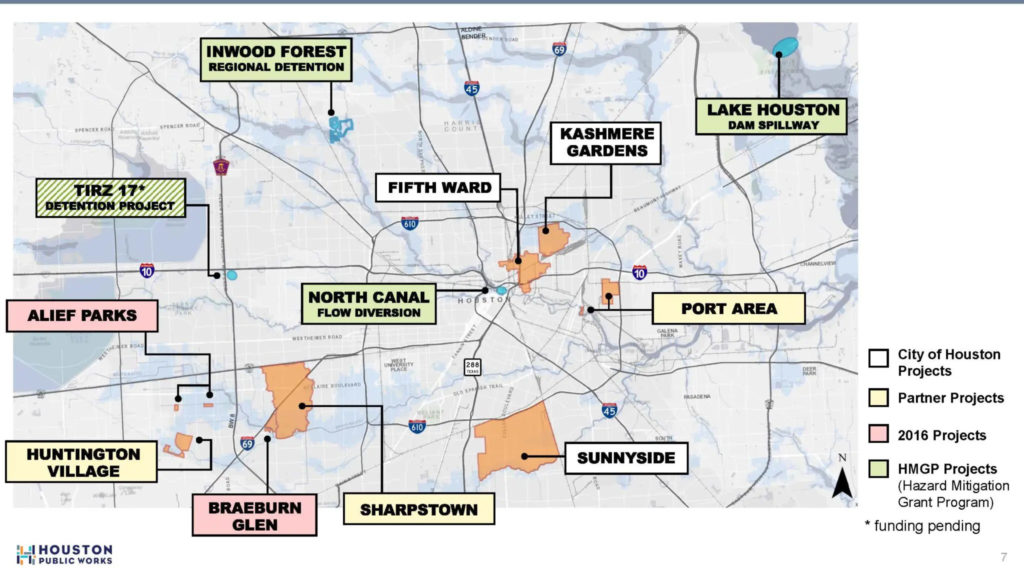

Costello previously served as the city’s flood czar, and was appointed in 2018 to lead the Harvey recovery by Mayor Sylvester Turner. His goal over the last five years, has been not just to repair damaged infrastructure, but to design projects that will serve as sustainable upgrades. He’s primarily in charge of designing four large-scale flood mitigation projects, that are currently in various stages of implementation.

However, securing federal funds necessary to begin construction has been a challenge. Additionally, construction costs have skyrocketed with inflation, causing project costs to increase by 20-40% since the grant applications were initially submitted, according to Costello.

“None of the projects I’m working on have been able to turn dirt yet,” says Costello.

Construction has yet to begin for the city’s marquee “North Canal Project” , which aims to provide flood protection to 30,000 commercial and residential structures downtown, and along White Oak and Buffalo Bayous.

Additionally, the city is waiting on money to start construction on the Inwood Forest Stormwater Detention Project to lower flood risk for 12,000 homes in and around Acres Homes; the Memorial City Subterranean Detention Vault Project which will impact up to 10,000 homes south of the mall; and the Lake Houston Dam Spillway to protect 20,000 structures upstream.

The Tirz 17 Detention Project, Inwood Forest Regional Detention, Lake Houston Dam Spillway and North Canal Flow Diverson (all highlighted in green) are HMGP projects that have yet to begin.

Houston officials have been wrestling with the Texas General Land Office over control of nearly $1.3 billion dollars in federal flood recovery money.

“Occasionally, you get a direct allocation to the city, bypassing the state,” Costello says. “We were advocating for bypassing the state, because we felt like we could deliver the projects quicker.”

The GLO points out that the city has missed deadlines on some projects and the state agency has clawed back portions of the money so that it can control how it’s spent.

What money Houston has been able to get so far has allowed it to work on smaller projects. The city has bought at least ten properties to create stormwater detention, spent over sixty million to elevate nearly three hundred homes, and improved stormwater drainage in various parts of the city.

Houston also plans on building two dozen flood resilient multi-family apartments in the next two years that will provide over thirty five hundred affordable units.

New building codes went into effect in 2018 after city council passed an ordinance,setting the 500-year floodplain as the minimum standard for new home construction. It requires new homes be built up to two feet above ground. The previous code only requires property to be built one foot above the 100-year floodplain.

“The Goal is 3,000 homes.. And that’s 3,000 new homes.. So That’s not counting the homes that are being repaired, or being replaced.. That’s just really new construction and allowing first time homeowners, the opportunity, to purchase homes,” says Keith Bynum, director of Houston’s Housing and Community Development.

Some experts question whether new flood resilient homes and developments can be built in the city, since most of the major flood mitigation projects haven’t begun construction yet.

“Development is still happening in the floodplain. And even though they try to take steps, they’re not totally in control of it because runoff from one property, is going to run off into another property,” says Shannon Van Zandt, Senior Fellow, Hazard Reduction & Recovery Center at Texas A&M University.

One area Harris County is hoping to improve is stormwater retention in the Cypress Creek watershed, where thousands of homes flooded during Hurricane Harvey.

The Harris County Flood Control District says they need to build infrastructure capable of holding 25,000 acre feet of stormwater to adequately protect that area.

The district is eyeing the Raveneaux Country Club, and the adjacent golf course, in order to start that process, since it potentially could hold a couple thousand acre feet of stormwater.

“We’ve built about 61,000 acre feet of volume across the entire county,” says Alan Black, Deputy Director of Engineering and Construction, Harris County Flood Control.

“So the potential for storm water detention on the grounds of the Raveneaux Country Club is a big step towards, but it’s also not the solution.”

Harris County currently owns 27.6 acres, and has already demolished the country club that stood on those grounds. The county is negotiating to acquire the other 206-acre golf course needed to complete a functioning stormwater retention basin.

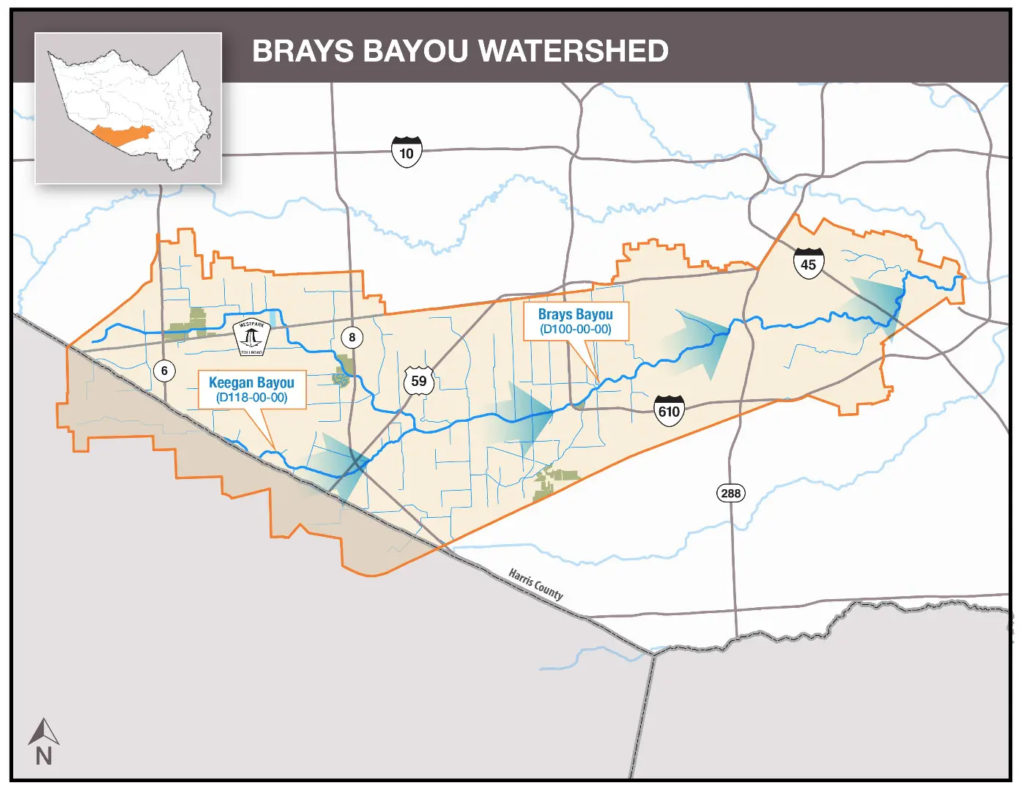

Harris County has completed one big project, necessary to improve Brays Bayou, which stretches west along the 610 inner loop, just south of downtown.

Harris County has completed the Brays Bayou Watershed, which stretches west along the 610 inner loop.

Crews just finished the 30 year venture, digging and improving four basins large enough to hold over 3 and a half billion gallons of stormwater. It’s the largest project Harris County Flood Control has ever completed.

“It’s going to deliver a lot of benefits to our community. We’re reducing the risk of flooding for over 15,000 structures in the Brays Bayou Watershed,” says Tina Peterson, Executive Director, Harris County Flood Control District.

The project started before Harvey. After the hurricane, Harris County voters passed a $2.5 billion dollar bond in 2018 to fund projects that can protect the region from future floods. So far, nearly two hundred projects are underway because of that money.

The caveat is, like the city of Houston, many of the projects are waiting on matching federal dollars currently being held up by the Texas General Land Office.

The GLO had previously decided that Harris County and Houston should get none of the 2 billion dollars in federal funds given to Texas to protect the state from future floods. After Texas Housers and the Northeast Action collective filed a complaintwith the Department of Housing and Urban Development for discrimination, the federal housing department ruled against the GLO. The city and county are still waiting on the money.

The county has been able to move ahead on 181 projects since they’re partially paid for by the bond and a flood resilience trust, until the federal money gets allocated. Officials say having the necessary money for construction, would avoid delays in creating a city more resilient to flooding.

That kind of resilience is what residents expect from local officials to help them recover more quickly from flooding disasters. People like Paula Sitter don’t want a repeat of Harvey where they have to wait years to move back home.

“This can’t just be about the bad that’s happened,” Paula Sitter says.

“It has to be about resilience and hope.”

If you found the reporting above valuable, please consider making a donation to support it here. Your gift helps pay for everything you find on texasstandard.org and houstonpublicmedia.org. Thanks for donating today.