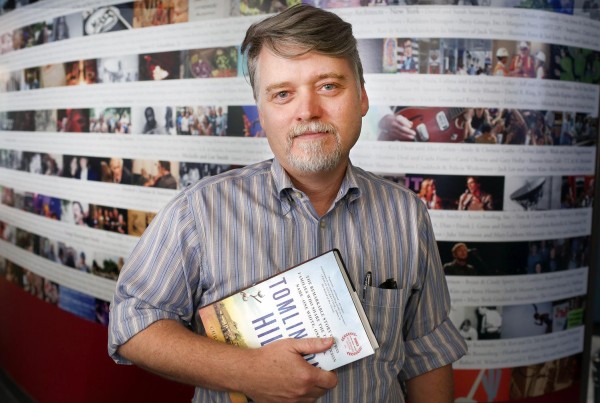

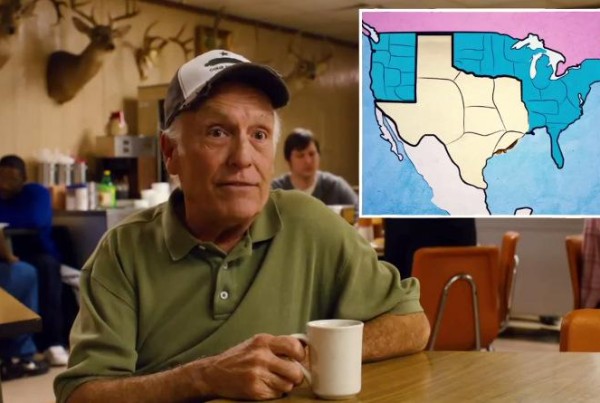

When you think of modern art, does Texas come to mind? According to Katie Robinson Edwards, curator of Austin’s Umlauf Sculpture Garden and Museum, it should.

Her new book “Midcentury Modern Art in Texas” highlights the localized manifestation of modern art in Texas, covering the Dallas Nine and the 1936 Texas Centennial, early modernism in Houston, the Fort Worth Circle, and artists at the University of Texas at Austin. But one of the book’s central, provocative questions is whether Texans are Americans within and without art communities.

Edwards explains to The Texas Standard’s David Brown that many people know about the Abstract Expressionism movement in New York City, but few people can name notable Texans who contributed to midcentury modern art, which covers art in the 1940s, ‘50s, and ‘60s.

She gave three examples: Forrest Bess, Benjamin L. Culwell, and Robert O. Preusser.

Bess received a lot of national attention for his eccentricity in his art and beliefs.

“Bess had a true belief in androgyny, that a human being should be emerging of male and female. He studied a lot of alchemy, he read extensively, and he’s notorious because he tried to physically change his body so he can be both male and female,” Edwards said.

Benjamin L. Culwell was drafted into World War II, and on his first day, he went to Pearl Harbor. During this time, he painted and drew. His work caught the attention of Dorothy Miller, the curator of the Museum of Modern Art at the time.

“He would get whatever paper he could from his officers. He would get crayons and melt them on a hot plate and make these encaustic works that are very expressionistic – they look like German expressionism – and horrifying,” she said. Edwards attributes the graphic nature of his work to what Culwell witnessed during the war.

Preusser grew up in Houston, studied art in Chicago, and acts as the “hero” of the book, with his artwork starting and ending the book. Aside from his artwork, he also taught at MIT.

“He ends up going to MIT [in 1954], spending the rest of his career uniting art and science,” Edwards said. “He gets very intense in always believing in the interaction between the visual, the performative, science, art, merging everything, putting architecture together and so a lot of what he did at MIT was teaching people that you need to function with all your engines at once.”

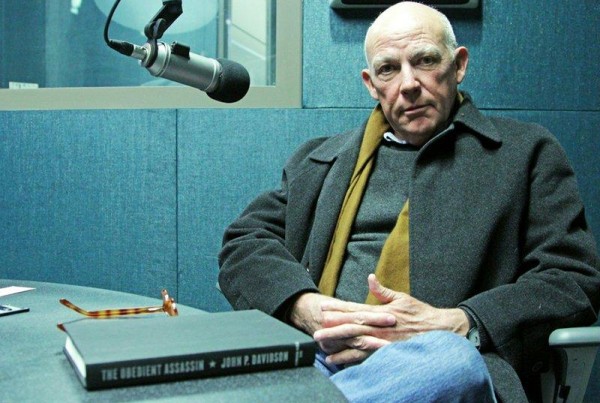

In addition to these artists, the books includes many other modernist painters and sculptors from Texas. One resource for Edwards was researching Dorothy Miller, one of the first curators hired by the Museum of Modern Art .

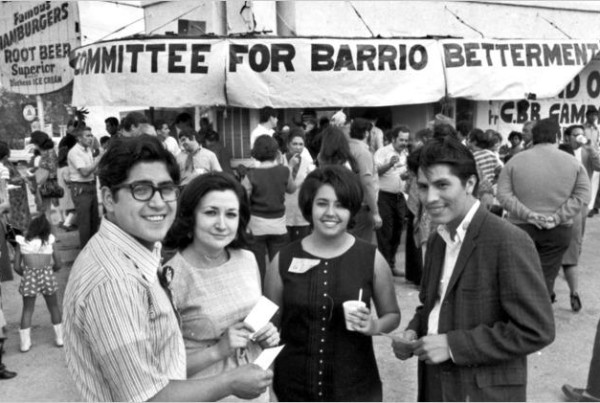

Miller began the “Americans” exhibitions, a series of shows that highlighted, often yet-undiscovered, American modernists. Edwards found that many Texan artists made it into these exhibitions. At the time, however, Texas was still seen as a foreign place by the art world, according to Edwards. That perception is changing, says Edwards, and that’s why she included a chapter on answering the question, “Are Texans American?”

“Absolutely, [Texans] are Americans. What has happened is that we have an idea of American art that is very New York-specific and we haven’t been paying attention to what else was going on,” Edwards said. “That [Texan] independent spirit, go your own way, make your own art, affected modern art.”