As I was watching the Olympics, I began thinking about all the great athletes who have come from Texas and gone on to be the best in the world. Though not an Olympic champion, I thought of one Texan who stood unexpectedly at the pinnacle of his sport for an impressive number of years.

He was born and raised in Galveston. His life seemed defined by an incident that occurred when he was quite young. When he came home from school he would often avoid a bully who had once attacked him in the street. That bully was older and larger so he thought it best to stay out of his way. But Jack’s sister saw this and got angry. She insisted that he fight the bully. “In fact,” Jack remembered, “She pushed me into the fray. There was nothing to do but fight so I put all I had into it… and finally whipped my antagonist.”

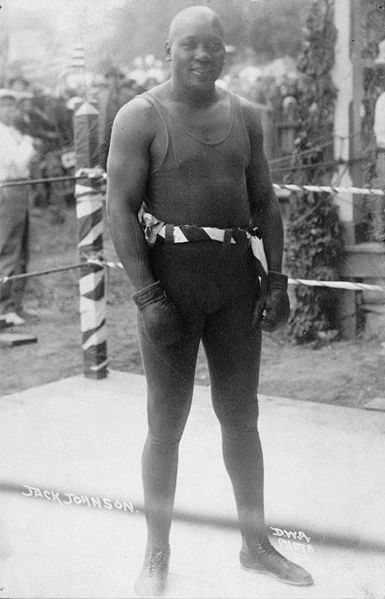

Jack’s reputation as a fighter was born. Later, working on the Galveston shipping docks, the vigorous work strengthened his muscles and toughened his body. He learned boxing from the stout men on the docks and began fighting in amateur matches, winning most all of them. This was the 1890s.

When he could learn no more in Galveston, he hopped a train out of there, hoping that would take him to a storybook future. In many ways it did.

Over the next decade, Jack became known in boxing as The Galveston Giant. The son of freed slaves, he worked his way through all the black boxers and some of the white ones, too, to get a shot at the World Heavyweight Champion, James Jeffries.

But Jeffries wouldn’t fight a black man. He claimed it was not something a champion should do. So rather than risk his title, he retired, undefeated.

Tommy Burns became the champion and Johnson chased him all the way to Australia and finally got a match. It would be in Sydney. Burns would get $35,000 and Johnson would get $5,000. Burns’ manager would referee the fight. It went fourteen rounds and it was stopped before Burns got knocked out. Johnson was declared the winner. He wrote in his autobiography, “The little colored boy from Galveston had defeated the world’s champion boxer and, for the first and only time in history, a black man held one of the greatest honors that exists in the field of sports…”

Jack London, the famous novelist, covered the fight for The New York Herald. He wrote, “The fight? There was no fight. No Armenian massacre could compare with the hopeless slaughter that took place today. The fight, if fight it could be called, was like that between a pygmy and a colossus… But one thing now remains. Jim Jeffries must emerge from his alfalfa farm and remove the golden smile from Jack Johnson’s face. Jeff, it’s up to you! The White Man must be rescued.”

And that is where the notion of The Great White Hope came from: Jack London.

The World Heavyweight Champion, Jack Johnson, accepted his victory with a contrasting humility. He recalled: “I did not gloat over the fact that a white man had fallen. My satisfaction was only in that one man had conquered another and that I had been the conqueror… The hunt for a ‘white hope’ began, not only with great earnestness and intenseness, but with ill-concealed bitterness.”

So people started sending telegrams and letters to Jim Jeffries, begging him to come back and take the title from Johnson. He initially repeated what he had said before: “I have said I will never box a colored fighter and I won’t change my mind.”

But money can work magic on prejudice. For the guarantee of $120,000 from promoter Tex Rickard, for the fight and the film rights, Jeffries signed on to what was billed as “The Fight of the Century.” It was held in Reno, Nevada, on July 4, 1910. It was well over 100 degrees at fight time – 2:30 in the afternoon under a cloudless sky. Johnson said the “…red hot sun poured down on our heads. The great crowd was burning to a crisp.”

The betting was heavily in favor of Jeffries – about 2 to 1. A reporter from Palestine, Texas, wrote that when Johnson was asked how he felt about that, he said, “I know I’m the short ender in the betting and I know why. It’s a dark secret, but when the fight starts we’ll be color blind. I’m going in to win.” And he did. He knocked out Jeffries in the 15th round.

Johnson said, “Whatever possible doubt may have existed as to my claim to the championship, was wiped out.”

Jack London agreed. He had called out for the great white hope himself and wrote that

Johnson had decisively defeated the white champion. London doubted that Jeffries, even in his prime, could have defeated this “amazing negro (boxer) from Texas.” He said he knocked down the man who had never been knocked down and knocked out the man who had never been knocked out. “Johnson is a wonder,” he concluded. “If ever a man won by nothing more fatiguing than a smile, Johnson won today.”

The film of the fight was considered an immoral display and banned in many states and cities. Governor Campbell of Texas cited those grounds in saying he would discourage authorities from showing it Texas and would convene the legislature to “promote this end.”

Muhammad Ali, who was often compared to Jack Johnson for his unshakeable confidence and easy-going banter in the ring, had enormous admiration for Jack Johnson. He said, “Jack Johnson was a big inspiration for what he did out of the ring. He was so bold. Jack Johnson was a black man back when white people lynched negroes on weekends. This man was told if you beat a white man we’re going to shoot you from the audience and he said well just go ahead and shoot my black butt cuz I’m going to knock him out. He had to be a bad, bad black man cuz wasn’t no Black Muslims to defend him, no NAACP in 1909 no MOV or any black organizations, no Huey Newton, no Angela Davis, no Malcolm X. He was by himself… He was the greatest. He had to be the greatest.”

My special thanks to my good friend James Dennis who suggested this topic as especially worthy of the Stories from Texas series.