From KERA News:

Kaleta Doolin, who’s 73, said she’s been working with steel since she was 16. Before that, as a young child, she created her own books. But at 16, she wanted to work in wood, wanted to become a carpenter.

“But my brother saw my first attempts at carpentry and he said, ‘Let me show you how to weld'”— and Doolin laughed.

Working directly with metal can be a visceral thrill for a sculptor. Use a torch to heat up a bar, and it becomes soft enough you can bend it with your (preferably gloved) hands. Or use the torch to cut straight through a steel plate. It can make you feel like Superman.

Or — Wonder Woman.

“I love that feeling of being powerful,” Doolin said.

A pair of Kaleta Doolin’s steel handkerchiefs being readied for the new show; behind them, “Waterfall.”

Jerome Weeks / KERA News

In fact, Doolin’s sculptures are often feminist statements precisely because they’re metal. She cuts and welds steel to make filigreed handkerchiefs. Quilts. Delicate doilies

Or about as delicate as you can make something with sheet steel.

But using metal this way, the kind of needlework historically associated with women is no longer so delicate: Doolin has sewn together a quilt of steel plates, using copper wire. She’s made an afghan from knitted yarn and chains.

“I’m making a statement about the strength of women,” she said. “I use my mother’s things, and I put it into steel.”

Some of Doolin’s art works are in leading museums in New York, Boston, San Francisco and London. And now, she’s getting a survey of some 30 years in her career, across 40 artworks. The show called “Crazier than Crazy Quilts,” and it’ll take up both locations of the Erin Cluley Gallery. One reason it needs such space is Doolin’s art varies in size from the hand-held — as small as trinkets — to steel sculptures you’d need a truck to carry.

Doolin credits her mother with inspiring her interest in handkerchiefs, needlework — what’s been termed “femmage,” the traditional “women’s crafts” like quilting or ceramics that only recently have been championed as more than “craft” or “kitsch.”

Her mother, Mary Kathryn Doolin, sewed clothes for her daughters, she knitted and crocheted. And she collected handkerchiefs — much like Kaleta still does.

“I love to crawl through antique malls. And I think overall, that mom’s collecting hankies influenced me. Hers were more utilitarian. But the ones I’ve collected are colorful and, you know, they’re much more ornate.”

Doolin made her first steel hankie back in the ’80s, she said, for her husband, Alan Govenar, the documentary filmmaker, playwright and music historian.

And as for scrounging for ‘found materials,’ there are also scrapyards.

Kaleta Doolin with her artwork, “Rusted Hankie.” The pattern was spray-painted on to the steel plate using the handkerchief as a stencil.

Jerome Weeks / KERA News

“I used to go to Liberty Metals” on Singleton Boulevard, Doolin said. “And they’ve closed to the public now. So I’m looking for a new scrapyard.”

Doolin especially likes old augers, those giant drill bits used to dig holes for water drains and telephone poles: She thinks augers have a feminine shape, and you can see that same kind of spiraling curve in some of her “non-auger” sculptures as well. She seems fascinated by waves and waterfalls rendered in metal.

Over her career as an artist, educator and philanthropist, Doolin has also specialized in videos and book art. In fact, perhaps her most overt feminist statement uses a classic college textbook, H. W. Janson’s “History of Art,” first printed in 1962. She read it in her SMU art classes in the ’70s but only learned later about its blinkered thinking.

“When I was doing a paper on women artists,” she said, “I found a reference that said Janson had no women in it, in the original edition. And I was really mad because I’d studied that for two semesters, and I’d never noticed.”

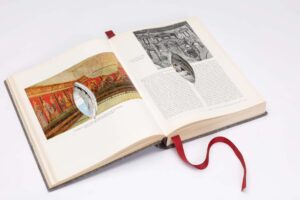

“Improved Janson: A Woman on Every Page” — the first edition of H. W. Janson’s classic textbook, “History of Art,” covered cave drawings to Kandinsky and did not include a single female artist. So Kaleta Doolin corrected that neglect.

Kevin Todora / Kaleta Doolin

So Doolin set out to put some women in it. In 2017, she sliced a vulva-shaped hole through all of the book’s 572 pages. Her title? “Improved Janson: A Woman on Every Page.” There are copies of the work in the DMA and the Brooklyn Museum of Art, and a number of female artists have since followed Doolin’s example.

Later, she used the cut-outs to create a hanging curtain-like mobile she called “Janson in Chains.”

On a recent morning, Doolin’s East Dallas studio was cluttered, as most atists’ studios typically are. But in addition to the usual unfinished projects, there were artworks being readied for the show, and workmen were fixing two doors. They’re the size of barnyard doors.

Doolin’s studio is in a two-story, red-brick building in East Dallas. More than a hundred years ago, it was Dallas Fire Station #16 — and it stabled their horses. Hence, the doors.

Doolin is the daughter of C. E. Doolin, the man who invented Fritos and Cheetos. She and her husband Alan bought the old fire station in 1991. They restored it, and over the years, it has served art gallery, office and now it’s her work place.

“I love it,” she said, standing amidst the boxes and welding equipment. “I love it. Yeah, this is – this is like home for me.”

Kaleta Doolin used her mother’s snow chains and nightgown, plus her father’s worklight, to create “Mom and Dad.”

Jerome Weeks / KERA News

Her parents were in the studio this morning – in spirit. One of Doolin’s works has a pair of snow chains hanging down.

“These are my mother’s tire chains,” she said, “from our trips to Colorado when we went skiing.”

Because she saw the chains stored hanging up, she noticed they naturally seemed to nip in — like a waist. So one set of chains has her mother’s nightgown, while the other set has her father’s worklight. The title: “Mom and Dad.”

But Doolin has done much more than make art. She’s taught, curated shows, juried prizes and co-founded the Texas African-American Photo Archive. In 1989, she established a foundation that supports the exhibition and encouragement of female artists — including acquisitions at the Nasher Sculpture Center and the Dallas Museum of Art. (In recent years, the Kaleta A. Doolin Foundation has expanded its efforts to include women in the sciences.)

This fall, the Amon Carter Museum will present a major show on the sculptor Louise Nevelson. Doolin’s foundation supported the exhibition and its catalog. Nevelson’s famous found-art sculptures are favorites of hers.

But unlike Nevelson, who typically created wooden installations the size of walls, Doolin’s work can scale down to the jewel-like, even the intimate.

“I love the delicacy,” she said, “and the strength, together.”

The title of one of her artworks says it all: “Steel Lace.”

“Crazier than Crazy Quilts” runs at the Erin Cluley Gallery and Cluley Projects April 1st through May 6.