The virtual reality training could be a tool in the overall effort to prevent suicides. The Air Force is currently testing the modules. Cadets had the opportunity to try the training in El Paso after a question-and-answer session at the end of Glick’s talk.

Lt. Col. Dana Bochte, Air Force ROTC Commander for New Mexico State University and UTEP, sees value in the virtual reality experience.

“You put the goggles on. There’s a little introduction and you’re put right into the scenario of confronting an airman or a guardian, you know, someone in the Space Force, who is having suicidal thoughts,” Bochte said.

As a squadron commander, she has seen the virtual scenario play out in real life.

“Quite a few times, both as a friend to peers who were really struggling” and with her teammates who “were crewed together for an entire month in Afghanistan,” she said.

Bochte has also seen others come forward seeking help, “either self-identified who came to me and said that they were having trouble, or were brought in by coworkers and friends.”

Prevention at Fort Bliss

Suicide affects every branch of the military. But the largest, the Army, had the highest number of suicides last year with 176 active-duty, 45 reserve and 101 National Guard troops according to the most recent quarterly report for 2021. There are 480,000 active-duty personnel in the Army.

Fort Bliss does not release the number of suicides among its soldiers “as a matter of policy,” according to a statement in response to a request for data.

“Regarding our Fort Bliss service members who succumb to suicide, each incident is a tragic loss that affects the service member’s family and teammates as well as the larger Fort Bliss family,” according to the statement.

At Fort Bliss, suicide prevention is a command-level priority.

Maj. Gen. Sean C. Bernabe, Senior Mission Commander, 1st Armored Division, launched Operation Ironclad in February 2021 to “combat harmful behaviors” with a focus on three “corrosives” including sexual assault, suicide and extremist behaviors and activities.

There are a range of resources for Fort Bliss’ 18,193 military personnel, including military family life counselors, chaplains placed in each battalion at the squadron level and higher, outpatient behavioral health clinicians and programs; and more recently an “evidence-based” group therapy program.

“We’re all-hands-on-deck regarding this very difficult issue,” said Lt. Col. Gordon Lyons, chief of behavioral healthcare at Fort Bliss.

“That is the goal of behavioral health services in the military – to make you better, stronger, so we have a stronger military and we’re stronger as a country and a nation for it,” Lyons said.

Lyons said his own struggles as a young person inspired him to enter the behavioral health field. He describes his role as a “travel guide” rather than a “tourist” for soldiers who seek mental health help.

Some soldiers, he said, can be at particular risk because of a combination of factors. Soldiers who had difficult childhoods, are currently experiencing problems with intimate partners and are young and often more impulsive need special attention if they are in crisis, Lyons said.

However, the newer generation of young soldiers is also often more willing to talk about mental health, he said.

“I think they’re leading the way as far as the societal change of being open and able to talk about mental, psychological and emotional issues in order to resolve our issues and be stronger as human beings as a result,” he said.

Dispelling myths about who is at risk of suicide, to include those with successful military careers, is also critical.

“Those people who are ‘hard chargers’ as we call them in the military, who are really on their game, getting things done, sometimes, often have high expectations of themselves. That can actually be a risk factor,” Lyons said.

The Fort Bliss Suicide Prevention Program provides training and education to create awareness at all levels. The mandatory training focuses on the ACE suicide intervention model which stands for “Ask, Care, Escort.”

During a half-hour session at William Beaumont Army Medical Center in March, the trainer emphasized ACE and led a discussion with soldiers about the barriers to seeking mental health help including the perceived stigma.

“We’re going in the right direction,” said Sgt 1st Class Antoine Riddick, 38, after completing the training.

“The more that we’re talking about it, educating ourselves and learning about it, the more I feel we’ll get away from the stigma,” he said. “And it shows we’re people and hurt like anyone else, and when we need help it’s ok to ask for help.”

Life-saving conversations

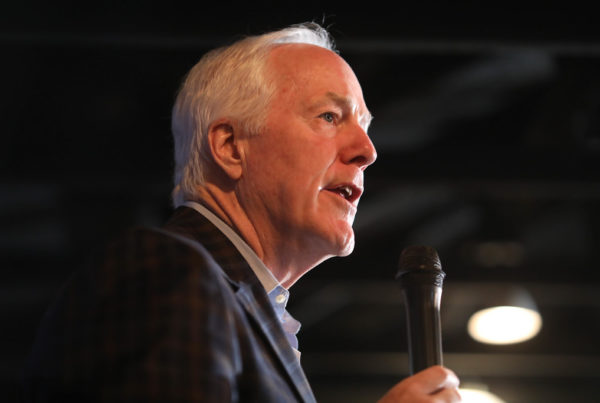

These days more military leaders are openly discussing their own mental health struggles. Glick is blunt about being treated for anxiety, PTSD and depression after multiple deployments.

“My first wife caught me with a gun in my mouth and she never talked to me about it after that,” he said. “And this is a very good human being, a spectacular woman, definitely a good military wife and a good mom.”

Years after they were divorced, he asked her why she didn’t ask about it. He said his ex-wife told him she didn’t want to upset him more.

“When you have somebody who’s a really good person feel like they can’t talk about it because they’re not equipped, that speaks to me. That means she’s not alone,” he said.

Teaching people to have those life-saving conversations has become his new mission.

Glick is in recovery. He found the help he needed and has remarried. He wants those in crisis to know things will get better.

“My life is wonderful every single moment,” he said. “And I think that there’s hope.”

If you or someone you know may be considering suicide, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 (En Español: 1-888-628-9454; Deaf and Hard of Hearing: 1-800-799-4889) or the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741.