From KACU:

The San Antonio River, also known as Yanaguana, has been spiritually significant to indigenous people for thousands of years. The river runs through Brackenridge Park and gives life to native wildlife and plants, including the huge trees that shade the riverbanks. Now, a city initiative to restore the historic colonial structures of the park requires the removal or relocation of at least 62 of those trees, and some indigenous people are fighting to protect them.

A 2017 bond program is funding a variety of projects across the city, including the revitalization of historic structures in Brackenridge Park, which is just north of downtown San Antonio. But the project involves cutting down or relocating trees in the area because their roots threaten the structures. Some of the trees have a trunk width of more than two feet, qualifying them as heritage trees,”These trees connect the underworld with the middle world, which we live in, with the upper world up in the sky. They’re the tall beings, and the birds carry it up even further into the sky.”

That’s Gary Perez, an Indigenous researcher. He calls this area “cosmology central,” saying the river, trees, and the annual alignment of constellation Eridanus all combine to build a bridge for his ancestors to cross over into the afterlife, “It’s more than just a river passing through Brackenridge Park. It’s part of a whole worldview, a whole way of life.” To Perez and other members of San Antonio’s Indigenous community, the trees in the park and the birds that nest in them are an essential part of heritage and culture.

The Brackenridge Park pumphouse is one of the historic colonial structures the city is working to revive.

In mid June, members of the community gathered around the Blue Hole, the spring that feeds the San Antonio River, for a summer solstice ceremony. They believe that this is where Yanaguana, the Spirit Waters, begins. Matilde Torres, an Indigenous cosmologist, explained Yanaguana’s creation story, “The water bird flew into the Blue Hole, and it encountered the Blue Panther. Once it encountered the Blue Panther, the water bird flew out. Immediately from its tail feathers, droplets of water fell onto the region, and that’s how life came to be.”

Torres says the waterbird referenced in the story is the double-crested cormorant, a migratory bird that annually nests along the San Antonio River. The double-crested cormorant, along with other migratory birds like the little blue heron and snowy egret, rely on the trees in Brackenridge Park to roost and raise their young, “Everything here is sacred to our people, and continues to be. These trees tell the story, the water, the spirit waters, continue to tell that story.”

Torres and others who value the park’s wildlife worry that removing trees will drive the sacred birds away from the area where they’ve nested for generations. Lynn Cuny, the founder and president of San Antonio Wildlife Rescue and Rehabilitation, describes the proposed removal of trees as, “ludicrous and dangerous” because the trees have provided food and shelter to countless animals for decades, “We should have learned by now that every time we move in and do something to change the basic natural structure and makeup of a creek, a river, a pond, it doesn’t matter what it is, there are serious consequences, and they are not good consequences, to the residents of those areas.”

“If we don’t take care of what we have now, we will have nothing later. We are losing wildlife at enormous rates because of what humans are doing. Case in point: City of San Antonio,” says Alesia Garlock, a wildlife photographer who has observed the birds at Brackenridge Park for the past five years.

Garlock, Torres and other environmental advocates have spoken up at public city meetings to oppose the tree removal. In response, project planners have reduced the number of significant trees set for demolition in phase one from 55 to 37, and they have reduced the number of heritage trees from seven to six. Officials say the remaining 19 trees will be relocated.

This oak tree is one of the oldest heritage trees in the park. Originally set for demolition, city officials have decided to relocate the tree a few feet away from the river wall it sits on top of to preserve both the wall and the tree.

Joe Turner is the executive director of the Brackenridge Park Conservancy. He says cutting down or relocating the trees is necessary for the preservation of the river walls,“It’s a huge historical piece of the city, and it’s a huge piece of how water was so important to the San Antonio and, quite honestly, San Antonio exists because of that river and that water that came from that river.”

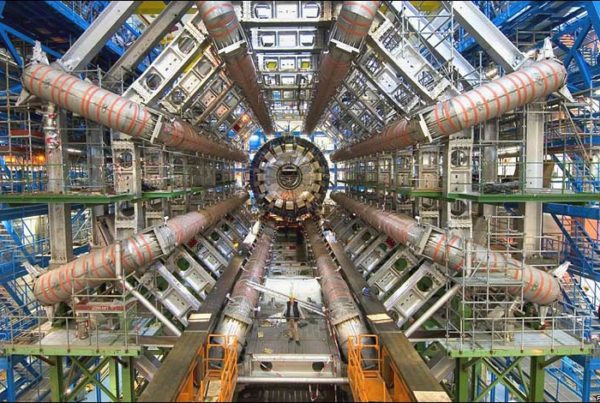

Crews built the walls in the 1920s in an effort to control flooding. Now, large tree roots and poor maintenance have left the walls cracked and collapsed. Critics say the damage leads to poor water quality.

Turner says the conservancy and the city are working to find ways to honor and preserve both sides of history. Homer Garcia, the director of San Antonio Parks and Recreation, says the city also plans to include input from Indigenous groups in phase two of planning the park’s development, “You get into a portion of the project where I think there’s a great opportunity to tell about the park’s history and all of the various cultures that have utilized it over time.”

With the phase one designs complete, the city will move on with three more meetings in July to discuss phase two and get public feedback. The city hopes to complete the project designs by September so they can be reviewed by the Texas Historical Commission for approval.

Scheduled meetings will be posted on the city’s website.