When there’s a vacancy on the Supreme Court, a president has the opportunity to fill that slot with someone who shares his or her political perspective and values. As a result, the president cements a legacy. But nominations can spark backlash from a opponents, which happened when Lyndon Johnson nominated Abe Fortas for chief justice as Johnson was finishing up his term as president in the late 1960s. Some conservative senators vowed to prevent the lame-duck president from pushing through his nominee. This happened more than 50 years ago, but it’s an echo of what’s happening today with our current president, his Supreme Court nominees and Congress.

Michael Bobelian, who writes about the Supreme Court for Forbes, examines the Fortas nomination in his new book, “The Battle for the Marble Palace.” He says Fortas’ nomination in 1968 was the origin of the hyper-politicized Supreme Court confirmation process that endures today.

Bobelian says that up until 1968, Supreme Court confirmations had been swift and uncontroversial affairs; the Senate had only rejected one nominee, in 1894.

“From 1968 [to] 1971, excuse my language, but all hell breaks loose,” Bobelian says.

Like others who closely follow politics and the law, Bobelian says he once thought the 1987 nomination of Robert Bork for associate justice marked the beginning of the era of contentious nominations. But he says, in fact, it was Johnson’s nomination of Fortas that started it all.

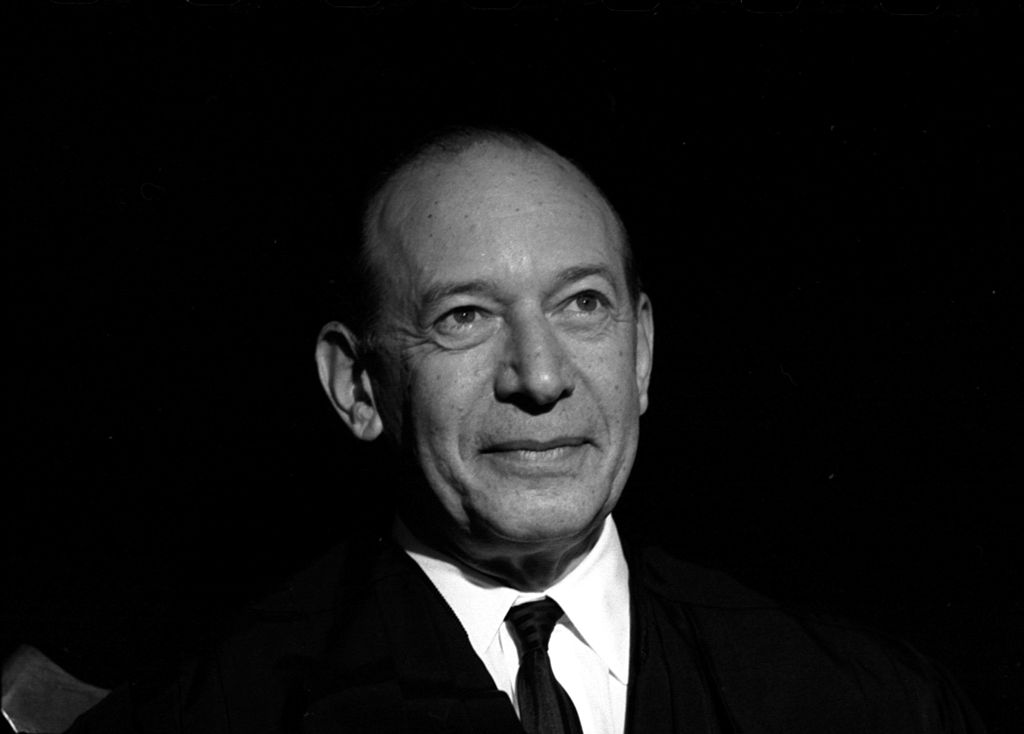

Fortas was considered one of the best lawyers in the country, Bobelian says. He was the son of Jewish immigrants who had worked in New Deal agencies during the 1930s, and he had served as Johnson’s personal lawyer and political advisor.

“He was called a ‘brain surgeon’ by his colleagues – the person you called in when all else fails,” Bobelian says.

Fortas was appointed to the Supreme Court as an associate justice in 1965. Johnson knew that Fortas would uphold his liberal policies, Bobelian says. But conservatives were aware that the court at that time, led by Chief Justice Earl Warren, was not friendly to their point of view, so they worked to diminish its power.

“By 1968, they realized that the way to control the court was to control its members,” Bobelian says. “And they now direct all their forces against Abe Fortas in implementing this new strategy.”

Ultimately, the Senate rejected Johnson’s 1968 nomination of Fortas’ for chief justice.

Bobelian says what happened in the 1960s did have some positive effects on today’s Supreme Court.

“We certainly have a more diverse Supreme Court in terms of opening the door to women, underrepresented minorities, who had not been on the court,” Bobelian says. “And Johnson and Nixon really started to open that up.”

Bobelian says today’s justices are also more highly credentialed than they were before. But there’s a flip side.

“The downside is that they’re much more ideologically focused, and a little bit too partisan, compared to more of the centrists you had in the middle of the 20th century,” Bobelian says.

Written by Shelly Brisbin.