From KERA News:

The vacant lots are directly across the street from an affordable housing project. They’re overgrown with weeds. Some are marked with “No Trespassing” signs and surrounded by chain-link fences. And there’s an unseen danger.

Underground, the soil is laced with heavy metals and the groundwater is polluted with chlorinated solvents.

As recent as last year, some of the city’s most vulnerable residents lived on top of that soil in homeless encampments that one local homeowner describes as a scene from the 1991 gritty crime drama “New Jack City.”

Ken Smith lives near the lots along Jeffries and Meyers streets in South Dallas and regularly passes through the area.

“What we saw was…housing tents all over here,” he said. “The drugs have moved to the next street, by the way. We haven’t resolved that issue.”

The camps are gone now. Local homeowners complained to the city and they were cleared out. The lots where they stood are among hundreds, if not more, of “brownfields” — mostly abandoned sites that developers spurn because of real or perceived environmental threats.

The City of Dallas recently got $1.5 million in federal dollars to start the first permanent brownfields program and to start assessing and cleaning up land in the targeted areas. How far that money will go — and how much success the program will have — remains to be seen.

This isn’t the first time Dallas has received money earmarked for brownfields. For almost thirty years, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has periodically granted Dallas money to assess brownfields for potential environmental risk.

So, what has that meant for people living near brownfields?

More often than not, the brownfields remain. Unchanged. Redevelopment is an elusive goal.

Federal regulators say that owners often abandon their plans to develop brownfields after they find out the extent of the environmental damage.

Finding success stories can be a a little like spotting a unicorn. City officials often point to the American Airlines Center and Victory Park which are located on a brownfield site. But they also acknowledge they lack “institutional knowledge” of how many brownfields have been redeveloped.

But land in Uptown costs dearly. Smaller brownfields, especially in low-income neighborhoods where any kind of development may be limited, don’t attract as much interest.

“One of the biggest drags on economic development is the cost for remediation,” Smith said. “You don’t know what’s underneath the ground, you can just guarantee that if you’re going to put a shovel in the ground, you’re going to probably come up with something that shouldn’t be there.”

‘A barrier to economic vitality’

Earlier this year, EPA Regional Administrator Earthea Nance was among the federal, state and city officials who turned out to announce the funding evaluate and clean up brownfields. The sparsely attended press conference was held at what was described as a brownfield “success story.”

“Where we are at now, the American Airlines Center and Victory Park, was previously a brownfield site,” EPA Regional Administrator Dr. Earthea Nance said during the event. “The property sat idle and was contaminated for years, until EPA and the city cleaned it up.”

Before the site remediation, the land was used as a city dump, a power plant and a railyard. The environmental cleanup took nearly two years and cost $10 million. The City of Dallas supplied another $125 million for “public infrastructure and other improvements,” according to a 2007 EPA press release.

There are an estimated 450,000 brownfields across the country, according to the EPA. The agency partners with cities and communities to help remedy the environmental issues associated with these sites.

Rep. Marc Veasy (D-Tex.) says the grant is a huge step toward cleaning up communities but more needs to be done.

“Across this country we have about 140 million people that live within a three-mile radius of a brownfield site,” Veasy said at the press conference. “We can’t appropriate enough money. But we have to do what we can.”

The American Airlines Center and Victory Park were once a landfill, a railyard and powerplant.

Johnathan Johnson / KERA

In recent decades, Dallas has been hailed as a national leader in development and big business opportunities. But according to the city’s application for federal funds, “while Dallas has grown by 75% since 1970,” South Dallas and Fair Park have declined dramatically by 50%.

“White flight,” racist local policies and the migration of industry all played a role. The pollution remained. And the predominantly minority South Dallas and Fair Park communities had to live with the consequences.

“You’ll find that neighborhoods are blighted because they’re around contaminated sites,” economist Sarah Scott said. And many of those neighborhoods are in southern Dallas.

Scott wrote her 2010 doctoral dissertation at the University of Texas at Dallas focused on South Dallas and the Texas Voluntary Cleanup Program — the state-run brownfields initiative.

The most recent funding will target properties like the Park South YMCA, vacant lots in the Jeffries-Meyers area, the Forest Theater and a retail plaza on Holmes Street in the Forest District area.

Scott says brownfield sites pose more than environmental threats to communities.

“The presence of brownfield sites in neighborhoods is a barrier to economic vitality,” Scott said. “A brownfield not only affects the specific property…but also devalues the surrounding area and can act as a barrier to revitalization to a community at large.”

‘Willing to put their money behind it’

Annie Evans is the director of the Southfair Community Development Corporation, a nonprofit focused on affordable housing and community resources in South Dallas. The group owns most parcels along Jeffries and Meyers streets.

The lots were evaluated in 2008 and environmental researchers said at the time “additional investigation” was necessary based on the preliminary findings, according to EPA records. The properties have been mostly vacant for nearly two decades.

Evans says at one point, Southfair was partnered with a large bank who had pledged to help support a few development projects — but that didn’t last forever.

“Out of that divorce, we got to keep the land,” Evans said. “Once the partner with the deep pockets, like a bank has, leaves a small nonprofit, it does slow down the [development] process.”

Scott says these different types of investments directly relate to the success of a brownfield project.

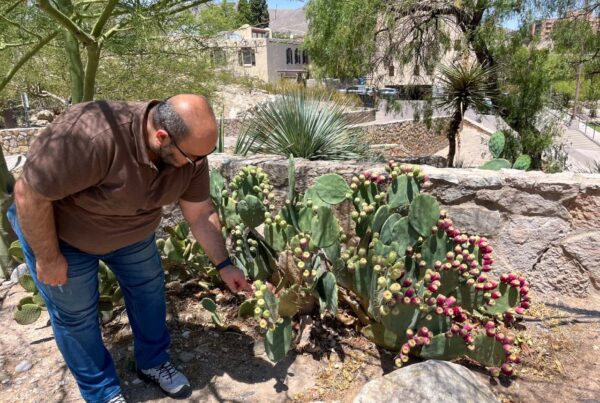

An aerial shot of vaccant lots that back up to a live foundry along Meyers Street in South Dallas.

Yfat Yossifor / KERA

“A lot of it had to do with…the public private partnership and the money that was invested in this property,” Scott said about the American Airlines Center and Victory Park project. “There were people who were interested in this and willing to put their money behind it.”

The American Airlines project also had another advantage — the land overlapped with four TIF districts which “enabled special tax treatment,” according to Scott.

TIF districts allow the city to give estimated property tax revenue to developers up front, as a development incentive. Most districts specifically outline funds to take care of “environmental remediation” as a TIF incentive.

Cleaning up another large site in Dallas — one located far away from trendy Uptown — proved to be more difficult.

“It was within the Cadillac Heights subdivision in east Oak Cliff,” Scott said. “The area was set aside for Black residential use…in 1947. So it’s got its feet in history, just like most of Dallas.”

The neighborhood was immediately adjacent to heavy industry, like former lead smelters. As a result, the property around the industrial sites has been contaminated.

“The operation of these facilities caused really high lead content in the surrounding neighborhood,” Scott said.

The two lead smelters were operating right across the street from each other in the area in the 1940s. Researchers say Cadillac Heights residents’ blood lead levels decreased only after the smelters were closed – in the early 1990s.

“The companies were smelting lead from batteries and slag, releasing dust clouds over these communities,” researchers wrote in a 2018 paper looking at lead exposure’s effect on kidney function

The Center for Disease Control says that there is no safe blood lead level in children — and even low levels of lead have been shown to “negatively affect a child’s intelligence, ability to pay attention, and academic achievement.”

Scott says the initial cleanup of Cadillac Heights started under the EPA’s Superfund program, but the remaining work was completed by the landowners through the Texas VCP — after facing possible litigation for their part in polluting the area to begin with.

“With American Airlines Center it was done with a huge push and a lot of money,” Scott said. “[Cadillac Heights] was done begrudgingly.”

‘A costly process’

A contaminated lot on Meyers Street in southern Dallas.

Yfat Yossifor / KERA

Part of the new funds will be used to start a Revolving Loan Fund (RLF) that essentially creates a bank allowing the city to “provide loans and sub-grants to carry out cleanup activities.” But the funds won’t be available till the Fall. Only the property owners can receive funds for cleanup — and only up to a certain amount.

“We need to build up the revolving loan fund portion of the program, so we can lend out money for cleanup,” Office of Environmental Quality Director Carlos Evans said in early June. “Again, we just received the funds so we have to figure out all the details.”

The RLF funds will be the first grant the city has received specifically for remediation. According to the EPA, this is the first time the City of Dallas has applied for cleanup funds.

“It’s a costly process. We’re a small nonprofit,” Evans said. “We don’t have access to an undetermined amount of funds to get things done.”

Unlike a corporation setting out to build a basketball arena, restaurant compound or even high-end apartments, organizations focused on affordable resources face higher financial burdens — where environmental remediation is only one of them.

“We’re looking to make things affordable,” Evans said. “We’re having to watch what we spend and look at what grants and support we can get to keep those developments low and affordable for our clients.”

City officials say the timeline for grant funding is around four to five years. The first two years are dedicated to site assessments and remediation plans. The rest of the timeline is for completing the individual projects.

Along with Southfair’s land, ten other sites that span multiple addresses and parcels were identified for use of EPA funds. City officials say the number of sites will increase in early October once they start accepting additional site proposals.

Until then, community members and property owners will wait to see the extent of decades-long contamination — and development realities — to become clear.

“Just because we make an announcement of about $1.5 million, there’s probably $100 million worth of remediation that needs to be done,” Smith said at an early June press conference. “This is a drop in the bucket.”

‘No obligation’

Just across the street from the Dallas Police Department headquarters, there’s a cluster of buildings and a parking lot. Not that long ago, it was a brownfield.

According to a 2004 assessment, private homes, commercial warehouses and even “a smelting and refinery facility” that had once occupied the surrounding area, as far back as 1915 through the mid-1970s.

Like the brownfield that’s now home to the American Airlines Center and Victory Park, the site was in an area that experienced something of a resurgence. It’s not far from a massive Sears warehouse that was transformed into the upscale South Side on Lamar Apartments.

Even though the assessment indicated that the site had issues, rising property values make brownfields more attractive to developers. But property owners often will decide not to move forward with cleaning up a contaminated site after an assessment — especially if the cost-benefit analysis doesn’t work out in their favor.

“That happens all the time,” Paul Johnson, an EPA project manager, said. “There’s no obligation for that entity to move forward.”

Johnson says that before a property can be assessed, the EPA must sign off on the project. But he says there are no contractual obligations after the assessment has been finished.

After a brownfield is assessed, finding out if it ever gets cleaned up is difficult. That’s because the EPA does not require the cities who are the grant recipients to report on remediation projects after the grant has expired.

“That grantee…once the grant period is over, is not obligated to update us on what’s going on with that site or property,” Johnson said. “We ask them to, we try to encourage them to do so, but they’re not obligated to do so.”

Johnson says that most grants are awarded to municipalities like the City of Dallas. Staff turnover often is high. And after a grant has expired, there may not be anyone around who’s still familiar with the project.

KERA News asked City of Dallas officials how many brownfield sites have been fully redeveloped. The response didn’t help much.

A Dallas spokesperson said that would require a “detailed open records review of past brownfields programs conducted in the City of Dallas since the 1990s.”

KERA has submitted a request.