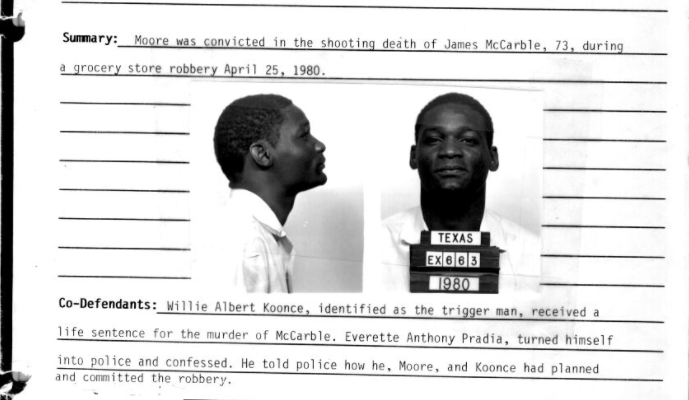

In April 1980, Bobby Moore shot and killed a grocery store clerk in Houston. His lawyers argued that he was intellectually disabled, citing the fact that he couldn’t tell time or understand the concept of the days of the week – even as a teenager. Moore was sentenced to death three months later for capital murder and has lived on Texas’ death row for more than three decades.

All of this happened before 2002, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that executing inmates with intellectual disabilities is unconstitutional. Yet Moore remained on death row because Texas devised its own standards for determining whether an inmate has an intellectual disability.

The Supreme Court ruled in Moore’s favor yesterday, and in doing so, invalidated Texas’ method for deciding whether an inmate is eligible for execution.

The 5-3 ruling found that Texas’ refusal to use current medical standards and its reliance on non-clinical factors to determine intellectual disability violates the Eighth Amendment, and therefore constitutes cruel and unusual punishment.

Jordan Steiker, a professor at the University of Texas School of Law and a former U.S. Supreme Court clerk, says that he was not surprised by the ruling.

“I think the oral arguments signaled considerable concern by the justices with Texas’ approach to defining intellectual disability,” Steiker says.

Texas uses the Briseno standard, which the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals established in 2004. It’s also known as the “Lennie Standard” – based on Lennie Small from John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men”. Lennie, characterized as an adult with the mind of a child, was pointed to as an example – he would be exempt from the death penalty “by virtue of his lack of reasoning ability and adaptive skills.”

The standard is largely based on a medical definition from 1992 and takes into account non-clinical factors, such as whether someone is capable of lying in his own interest or whether a person’s childhood family and friends viewed him as intellectually disabled. Steiker says these are “things that professionals would never use as the touchstone for determining the presence or absence of the condition.”

Steiker says the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals devised its own standard to limit the number of people who could benefit from the Supreme Court’s execution exemption.

“[It] was pretty much directly in defiance of what the Supreme Court had held,” he says.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who wrote the majority decision, said that states may not disregard current medical standards and she charged Texas with taking into account factors rooted in stereotypes.

The decision also laid out a general framework for determining intellectual disability that rests on proof of three things: low I.Q. scores, a lack of fundamental social and practical skills, and the presence of both of these conditions prior to age 18.

Moore’s case will be sent back to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, which will review a lower court’s previous ruling that found Moore did, in fact, have an intellectual disability.

Although the Supreme Court’s decision directly pertained to Moore, it will likely force a reexamination of several dozen death sentences in Texas for inmates who were denied an exemption from the death penalty based on the state’s approach.

“If the courts applying the right standard find that they do have intellectual disability, they would be exempt from capital punishment,” Steiker says.

Written by Molly Smith.