From KERA:

When Tarrant County Sheriff Bill Waybourn started his job in 2017, one of his first priorities was setting up a partnership with federal immigration enforcement. Within six months, it was done.

That became one of his most controversial decisions, and it’s one of the main issues in his current fight for reelection.

The partnership is called a 287(g) agreement, and it allows local law enforcement agents to train and act as federal immigration agents. According to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the goal is to identify undocumented people, flag them for ICE and begin deportation proceedings. In Tarrant County, that means certain sheriff’s deputies carry out these duties with inmates who enter the Tarrant County Jail.

The sheriff’s main job is to run the county jail. Waybourn, who spent decades as the police chief of the small city of Dalworthington Gardens, won the sheriff’s office in 2016, unseating longtime sheriff and fellow Republican Dee Anderson.

His challenger this year is Vance Keyes, a Democrat and a 20-year veteran of the Fort Worth Police Department, where he’s currently a captain.

Keyes has vowed to get rid of 287(g) if he wins the election. He said the agreement undermines public safety, because it undermines trust in law enforcement.

“If I’m an undocumented person, you can say what you wanna say. If I believe that you’re gonna arrest one of my loved ones or deport one of my loved ones, I’m not gonna call law enforcement if I’m a victim or if I’m a witness,” he said.

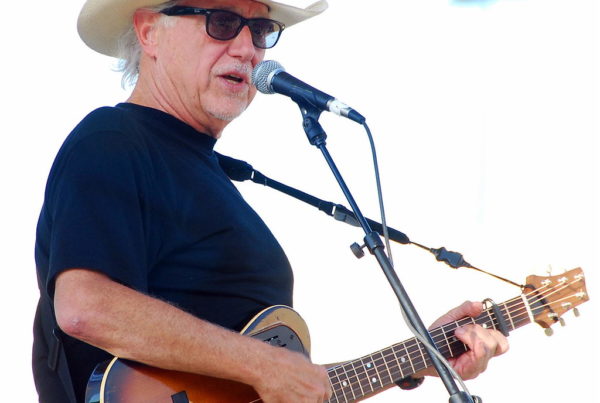

Vance Keyes, a Fort Worth police captain, is running for Tarrant County Sheriff. Keyes says the current administration under Bill Waybourn isn’t open enough with the public about what’s going on inside the Tarrant County Jail.

The sheriff’s office shared data about the program during a Tarrant County Commissioners Court meeting this past June.

From June 2019 through May 2020, Tarrant County sheriffs’ deputies flagged 307 people in the jail.

Of those, 236 people were released to ICE custody, and 70 were deported. Another 61 left the country voluntarily.

The Commissioners Court signed off on the original agreement in 2017 and renewed it again in June.

County Judge Glen Whitley, a Republican, expressed some reservations about separating families, but he said the program is worth it if it keeps even one person from being hurt by someone who was released from jail instead of held in custody.

“I can tell you, if it was a relative of mine, if it was a friend of mine, then I would look at that and say, I’m glad I did it,” he said.

Keyes said the sheriff’s office has no business doing the federal government’s job. Only 27 of the 254 county sheriffs’ departments in Texas participate in the 287(g) program, which is voluntary.

In an interview with KERA, Waybourn defended the program as a helpful law enforcement tool.

“If we don’t use our own discretion in order to hold them fully accountable, then we’re sending them back into the neighborhoods,” he said, referring to the undocumented inmates in his jail. “So if we have a responsibility to have safe neighborhoods, then law enforcement should cooperate together.”

He put it in even stronger terms during a White House press conference last year, when criticizing a federal court ruling that raised the standard ICE would have to meet to detain someone.

“If we have to turn them loose, or they get released, they’re coming back to your neighborhood and my neighborhood. These drunks will run over your children and they will run over my children,” Waybourn said.

His remarks about releasing immigrants who are repeat offenders drew criticism from Texas Democrats.

When asked for the number of people flagged by the 287(g) program who have committed violent crimes, a spokesperson for the sheriff said the department does not keep that data.

“The crimes that subjects were arrested from are not broken down into violent and non-violent, but by misdemeanor and felonies,” the spokesperson wrote in an email.

That’s a problem for Vance Keyes.

“If you tell me you’ve got this project, in a county of 2 million-plus people, and you snared, or you netted 300 people, but then you can’t give me numbers on these egregious crimes? I’m gonna call baloney,” he said.

Others question whether the severity of the crime should even matter.

Jonathan Guadian is an organizer with ICE Out Of Tarrant, an organization that advocates against 287(g).

“These people are being arrested and deported for the same offenses that citizens are committing in any case, and those people are able to remain here in the country,” he said.

Number Of Deaths Among Inmates Jumps In 2020

Immigration has been an issue throughout Waybourn’s first term, but a new concern has come up this year: jail deaths.

According to the Texas Office of the Attorney General, 10 Tarrant County Jail inmates have died so far in 2020. That’s more deaths than in the previous three years of Waybourn’s tenure combined.

Some causes of death are still pending, but so far, COVID-19 is responsible for only one.

Waybourn blamed his inmates’ preexisting conditions.

“I don’t think they fall on me to prevent other than that I provide good, reasonable care, and be alert to those things when they happen, and we’ve done that,” he said.

But some have questioned that level of care.

One inmate died by suicide after guards failed to follow the schedule to check on him.

The jail lost state certification for six days, which means it failed to meet minimum standards.

County Commissioner Devan Allen, a Democrat, learned about it in the newspaper. She confronted Waybourn at a meeting in June.

“If you quite honestly didn’t bother to tell us this, then what else is going on that we perhaps don’t know, but yet we’re being asked to, on a regular basis, provide additional resources to you and your organization?” she said.

Waybourn did tell County Judge Glen Whitley about the loss of certification, and Whitley said Waybourn followed protocol.

But that’s not enough for Vance Keyes, who is running on a promise of transparency. He said the sheriff needs to be more open about what goes on inside the jail.

“‘Cause I would say, well, sheriff, yes, you just had a bad year, these things happen, they’re beyond your control,” Keyes said. “When there’s a lack of transparency and competent accountability, I don’t know what’s going on.”

Waybourn said he’s accomplished a lot in his first term, and will continue to help inmates transition back into the community once they leave custody.

“I have this philosophy that a large majority of these people that are in jail today will be our neighbors again,” he said.

Now, it’s up to the 1.2 million registered voters in Tarrant County to decide who should wear the sheriff’s star for the next four years.

Got a tip? Email Miranda Suarez at msuarez@kera.org. You can follow Miranda on Twitter @MirandaRSuarez.