From KERA:

The Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Lab at Texas A&M University in College Station is two stories of offices and exam rooms filled with sophisticated machines. The lab is one of the largest of its kind in the country. Typical customers are ranchers, dairy farmers, and veterinarians.

“It’s a busy lab, and at times it’s almost factory-like,” said Terry Hensley, assistant director of the lab. “They’re coming every day and it’s like it never stops.”

Around the country, veterinary medical labs like this one are using their resources to do much-needed coronavirus testing on human samples. One of the machines here — called a PCR — is the same machine human labs use to diagnose COVID-19 in people.

Oklahoma State University’s vet lab, in fact, runs more human COVID-19 tests than any other lab in that state.

Texas A&M University’s Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory in College Station.

Together with another site in Amarillo, the lab analyzes hundreds of thousands of animal samples a year.

Lab director Bruce Akey said that early on in the pandemic, he wanted to contribute to the public health response to the novel coronavirus. So he set out to get the approval he needed.

“A, it’s the right thing to do. B, it’s the right thing to do. And C, I knew that the capabilities that we had would enable us to run exactly the same PCR tests that were going to be used for human testing,” he said.

Akey estimated his lab could easily do 300 to 500 COVID-19 tests a day, and potentially much more.

Texas A&M, however, found itself tangled in red tape.

PCR machines are used for coronavirus testing in both humans and animals.

State regulators, which do the certification review on behalf of the federal government, denied Akey, citing federal regulations. When he appealed to the federal agency that oversees human testing labs, he was told his top staff couldn’t direct the testing because their credentials are for animal samples.

Typically, that makes sense, Akey said. But he was hoping for more flexibility while the United States is under a national emergency.

“I do want to emphasize that,” he said. “There’s the regulations they follow under normal circumstances. These are not normal circumstances.”

Regulations for labs that analyze human samples are called the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments, or CLIA. The federal agency that oversees CLIA is the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, or CMS.

CMS wouldn’t do a recorded interview for this story.

“CMS is working closely with laboratories across the country to ensure that those seeking to perform COVID-19 testing can begin testing as quickly as possible,” they said in an email.

In answering written questions, CMS said it accepts a veterinary degree for human testing, but in that case, a lab director would also need to be certified by boards that deal with human testing.

Akey said he doesn’t have that.

Texas’ Health and Human Services Commission referred questions to CMS. The U.S. Department of Agriculture, which regulates animal labs, also declined an interview request.

Eventually, A&M’s veterinary diagnostic lab came up with another way to help out. Akey found a nearby health care company with someone who did have the credentials to oversee human testing inside the College Station lab. This helped them secure a CLIA certification for the facility.

That company’s staff needed training, though, on Akey’s equipment.

“We’re good enough to train them, but we’re not good enough to actually run the test,” Akey said.

The health care company, CHI St. Joseph Health, began testing human samples at the vet lab in April. But they wouldn’t tell KERA the number of human COVID-19 tests their staff analyzes each day using the A&M lab.

So it’s unclear how much this high-tech vet lab, one of the first to try to help out with COVID-19 testing, is being used to fight the coronavirus.

Several large veterinary labs in other states have avoided this problem.

Hemant Naikare runs a lab at the University of Georgia. He got federal certification and hopes to start COVID testing by September.

“If these labs have the ability to do the testing and they’re given the permission, then we could really contribute to increasing the capacity of testing,” Naikare said.

Keith Poulsen runs a veterinary lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, which is on track to test students this fall. Poulsen saw what Texas A&M went through, and took steps to head off a rejection from the feds by partnering with a human lab at his university.

“What we’ve learned from Texas is that, A, Wisconsin’s a little bit different and B, we’ve partnered with that human lab to help us kind of navigate those CLIA requirements,” Poulsen said.

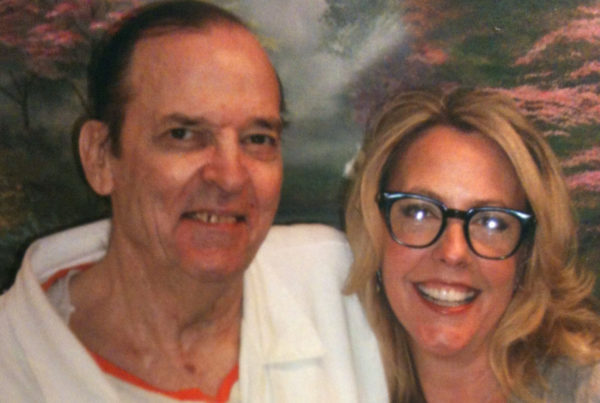

Lab director Bruce Akey. Photo by Bret Jaspers / KERA News

When asked why other labs were able to get permission for their staff to do human testing but Texas A&M’s vet lab was not, CMS said, “without having laboratory personnel reports for the labs, we cannot comment on the difference in staff qualifications.”

Akey said they searched for someone within Texas A&M who had acceptable credentials but did not find anyone.

COVID testing in Texas has been going up, but tests are still targeted towards high risk people or those with symptoms. Controlling an outbreak, however, requires widespread testing of people without symptoms too.

Akey has a lot of experience with animal disease outbreaks. When those occur, they test more than just the sick animals to know the extent of the spread.

“We need to test some of the clinically not-ill animals too,” he said. “Are the asymptomatic carriers [one percent] of the population or is that 30 percent of the population?”

Got a tip? Email Bret Jaspers at bjaspers@kera.org. You can follow Bret on Twitter @bretjaspers.