Plans for next year’s excavation are already in the works. There, archeologists and any volunteers, Indigenous people, and potentially some Indigenous youth will pick up where this year’s crew left off, digging further into the ground to continue uncovering Paint Rock’s history.

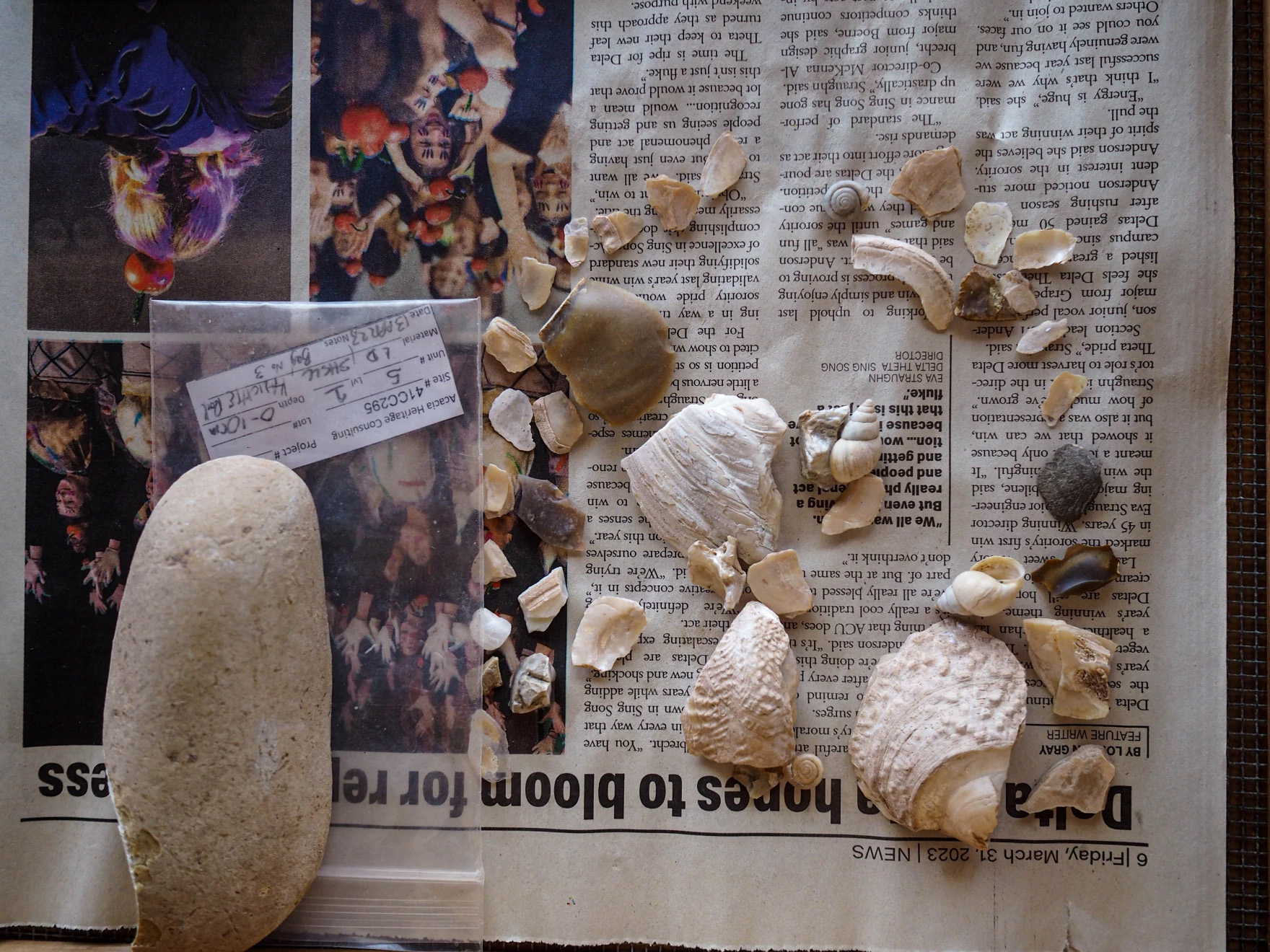

Comanche Elder Beverly Isaac shows volunteer Conner Strickland an artifact she found.

Sheridan Wood / KACU

From KACU:

Mornings on a typical archeological dig don’t usually begin with Indigenous prayer and song. But, at the first major excavation at Paint Rock, one of the largest rock art sites in Texas, dozens of Comanche, Lipan Apache, Payaya, and Otomi tribal members led the project just as much as the professional archeologists.

Eric Schroeder is the principal archeologist and editor of the Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society. He says while one tribal moderator is usually required at digs like these, having so many Native Americans on an excavation site is unprecedented in Texas archeology. “The archeologists wouldn’t get to do any interaction with the Native communities at this level where we’re actually talking to elders and a good, broad spectrum of the Native community.”

“We’re sharing information with the archeologists, and the archeologists are in turn sharing information with us,” stated Mary Weahkee. Of all of the professional scientists working at the site, she’s the only one who is both a professional archeologist and Comanche.

Weahkee says having Native peoples present at Indigenous sites is essential to understanding a site’s full context. “What an archeologist sees as a fire crack stone or a rock in C2 in the wall, was probably placed there on purpose for a reason. And they don’t know that because they never lived that life.”

Because of the unique understanding Indigenous people bring to these historical sites, Weahkee says she’s anxious for more Indigenous people to get involved in preservation work. “The culture is disappearing. We need to develop our own archeologists and anthropologists and biologists and do our own conservation and our own preservation to our own sites.”

While Weahkee works at archeological sites around the Southwest, this was a new experience for the majority of the Native people present. Many described feelings of connectedness and healing, including Cynthia Parker. “It’s inclusive. Even though we don’t know nothing about doing this, it makes you feel so included in something and that’s so important.” She’s a Comanche from Oklahoma.