Updated August 21, 2021 at 1:12 PM ET

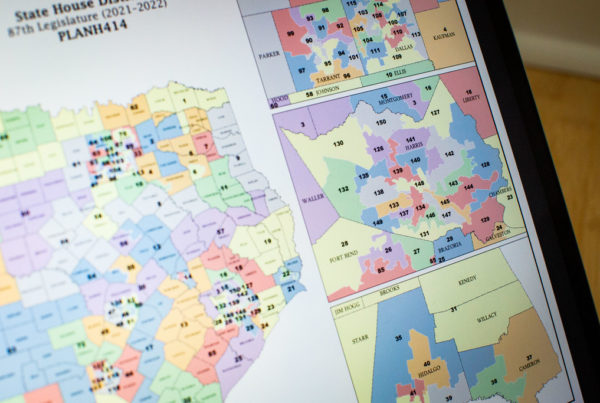

Some Texas Democrats who broke quorum last month have started to return to the state, which means lawmakers are starting to get back to work. In the coming weeks, that work will have to include the giant task of drawing new voting district lines for the state. Texas has grown more than any other over the last decade and has gained two additional seats in Congress.

Redistricting is historically a messy, contentious and partisan process no matter the state. This year in Texas, though, tension is already at an all-time high before lawmakers meet to draw new maps.

Political Chaos

In early July, a group of more than 50 Democratic members of the Texas House fled to Washington D.C. to deny Republicans – who have control of every part of state government – a quorum in that chamber. They left in an effort to block the passage of a sweeping bill that voting rights advocates say will make it harder for some Texans to cast a ballot.

Republicans have since retaliated by issuing arrest warrants. Gov. Greg Abbott also vetoed funding for the state legislature in response to Democrats walking out on a final vote on an earlier version of the voting bill in late May.

“It’s just basically opened up chaos,” says Stephanie Swanson with the League of Women Voters of Texas. Swanson says things have been rocky in Texas since that first quorum break, which will likely make redistricting even more combative this time around, “It has basically opened up Pandora’s box in Texas. The parties are at odds with one another and it’s going to be a bloodbath, to be quite frank.”

Civil rights attorney Jose Garza has sued Texas lawmakers over redistricting since the 1980s, largely in an effort to safeguard the voting power of racial minorities.

One of the big things that makes this year so different from past decades, Garza says, is how behind lawmakers are in the process.

“By now we would have plans that we would be analyzing,” he says. “We would have plans that people would have developed to compare against whatever came out of the legislative process. And we have none of that.”

Texas Is Changing

One major factor that has slowed state lawmakers is that data from the U.S. Census Bureau was released months later than usual during a redistricting year, due to delays from the pandemic and interference from the Trump administration.

That data shows that Texas lawmakers have a lot of work cut out for them in a short period of time. Population growth was bigger in the state than in any other over the last decade – 4 million new people, according to the 2020 census results.

Lloyd Potter, Texas’ state demographer, says most of that growth happened in the state’s big cities. At the same time, he says, more than 100 rural counties lost significant amounts of their population.

“That highlights even more what’s happening in these urbanized and suburban ring counties that it’s really intense in terms of the population growth,” he says.

New census data also shows Texas is becoming more diverse, with a vast majority of the state’s growth coming from people of color.

And groups are ready to sue if new maps don’t shift more political power to the state’s racially diverse communities and big cities and away from the state’s rural areas.

Anticipating Gerrymandering — And Much More

That creates challenges for Republican lawmakers as they try to draw maps that favor their party, says Genevieve Van Cleve, the Texas state director for a Democratic redistricting group called All on the Line.

“This scares Republicans,” she says.

Texas has a long history of violating the Voting Rights Act when it comes to redistricting. In fact, since the civil rights era law’s passage, the state has violated it during every redistricting cycle.

Garza says he’s seen Democrats and Republicans, alike, break up communities of color in Texas during redistricting cycles. And he doesn’t think this cycle will be any different.

“They are going to be slashing through minority communities in order to get this so-called political advantage,” he says. “They are going to be packing minority communities in order to gain this so-called political advantage,” and Garza says his group is prepared to fight that in court.

Swanson says lawmakers also have to sort out the funding issue for the legislature. Currently, legislative staff – including legislative counsel who are an essential group of people during redistricting – are only funded until the end of the current special session that ends early next month.

On top of everything else, Swanson says, there’s an election filing deadline at the end of the year.

“That doesn’t leave much time for the redistricting process to actually take place,” she says, “which is very concerning to a lot of advocacy groups here on the ground in the state who would like to see a robust public input process to take place.”

Van Cleve says this comes at a time when more advocacy groups in the state have been preparing communities for public input during redistricting this year than ever before.

“They are investing staff and money and political capital in ensuring that everyone in this state weighs in on redistricting and that that process is transparent and results in maps that reflect the population as it is now,” she says.