From Inside Climate News:

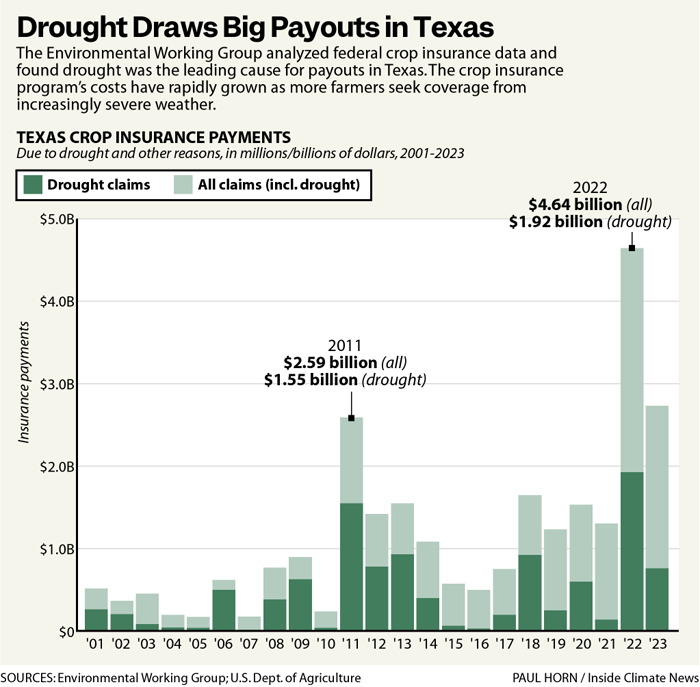

The financial costs of drought in Texas have risen rapidly over recent decades, according to a new analysis of federal crop insurance data.

The Washington-based nonprofit Environmental Working Group, a longtime critic of the federal crop insurance program, analyzed data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and showed that drought accounts for more crop insurance payouts than any other weather phenomenon and that Texas draws more crop insurance payouts than any other state.

Payouts due to drought in Texas rose from an average $251 million per year in the 2000s to $516 million per year in the 2010s, and $1.1 billion per year in the first four years of the 2020s, the data showed, rising at more than twice the rate of inflation.

Those numbers represent farmers’ lost harvests as well as the publicly-funded premium subsidies that keep them in business through disasters. As temperatures rise, so will costs.

“Drought and heat are expected to get worse in Texas,” said Anne Schechinger, author of the EWG analysis. “Climate change is going to increase costs for both taxpayers and farmers.”

Drivers of the growth in payouts include inflation, expanding insurance coverage and immensely damaging droughts in 2011 and 2022. The federal crop insurance program, which provides highly subsidized coverage to American farmers, is one of several insurance sectors facing financial headwinds from increased exposure to severe weather, driven in part by carbon emissions from fossil fuels.

As costs keep climbing, Schechinger said, the crop insurance program requires reform that encourages adaptation to long-term changes in temperature and rainfall. In 2022, the program’s most expensive year on record, it subsidized 62 percent of policyholder premiums at a cost of $12 billion, according to a review by the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

“You don’t want crop insurance to insulate farmers from market signals,” said Joseph Glauber, a former chairman of the federal crop insurance program and former chief economist of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. “You don’t want to encourage risky behavior. You don’t want to encourage growing crops on marginal land by virtue of the fact that you can insure it.”

In the last 30 years, crop insurance grew from a minor program to a massive safety net for American farmers and ranchers, Glauber said. That helps explain its rapidly rising costs, he said, driven by surging commodity prices during the Covid-19 pandemic (because crop insurance pays farmers market rates).

The program’s costs spike during years of drought, both in Texas and the nation. Drought can affect more farmers simultaneously than almost any other weather phenomenon.

“The problem with crop insurance is the same problem that we’re going to be facing with all the hazards that are associated with climate change,” said Bruce Babcock, an agricultural economist at the University of California, Riverside, who designed part of the modern crop insurance program. “There’s going to be a reckoning. We’re facing it now with the stresses that have been put on the insurance industry.”

Rising costs associated with extreme weather have posed challenges to other insurance sectors, too, said Mark Friedlander, a spokesperson for the Insurance Information Institute. The federal flood insurance program and home insurance industry have been particularly affected.

“We’re seeing just a lot of different perils and clearly the numbers are adding up,” he said. “Inflation and the frequency and severity of natural disasters are key cost drivers.”

The National Flood Insurance Program, a government-backed program to cover damage from high water in homes and businesses, is a “fiscal failure,” he said, based on an inaccurate assessment of risk. It is $20.5 billion in debt with $619 million in annual interest.

Last year the U.S. home insurance sector had its worst year since 2011, paying out $1.11 for every $1 it collected, Friedlander said, driven largely by severe thunderstorms. Another loss is projected this year.

“We expect to see rates continue to increase until it gets to the point where there is no more underwriting loss,” he said.

Insurance and cotton

In Texas, the EWG analysis found almost 60 percent of crop insurance payouts to date have covered a single crop: cotton, the state’s most widely cultivated crop. According to the nonprofit Plains Cotton Growers, 56 percent of the U.S. cotton crop grows in Texas.

Farming is a risky business, said Mike Oldham, a 68-year-old career cotton farmer in the Panhandle of Texas. When farmers plow a field and plant crops, they are gambling that favorable weather conditions allow them to grow the foods and materials that society needs. Bad weather can ruin all of that investment.

“If we don’t have [crop insurance], farmers aren’t going to stay in business,” said Oldham, whose farm has been in his family for four generations. “We’re gonna lose these rural communities and schools, banks, and also people lose their jobs. It just takes too many dollars to farm an acre of land without some kind of guarantee at the end.”

Oldham, who is also president of the Texas Farmers Union, said most farmers in Texas only insure up to 65 percent of their harvest and are not made whole after an extreme weather event.

Texas cotton farmers took a big hit in 2011, when the state’s driest year on record destroyed 62 percent of the state’s cotton crop. Brad Rippey, a meteorologist with the USDA’s Office of the Chief Economist, said that level of loss was “way off the charts.” After that, more farmers joined the insurance program, he said.

When severe drought returned in 2022, it dealt even greater damage—74 percent of the Texas cotton crop was lost. That year, Texas cotton farmers received almost $3 billion in crop insurance payouts. Without crop insurance, Rippey said, “it would have been an economic disaster.”

Even with crop insurance, the Texas Comptroller said the 2022 drought caused almost $8 billion in direct agricultural losses and nearly $17 billion in total losses. Cotton farmers lost about $2.1 billion in total economic activity, the Comptroller’s office reported, not including the losses covered by crop insurance.

“Although crop insurance helps producers recoup revenue losses, it doesn’t help businesses and consumers further down the supply chain,” the office wrote at the time.

Drought and adaptation

Although 2022 wasn’t as dry as 2011 overall, it was drier early in the year during planting season, said John Nielsen-Gammon, director of the Southern Regional Climate Center at Texas A&M University. By the time rains picked up in May, it was too late for the cotton.

Droughts are part of Texas weather and rising temperatures are making them worse. An assessment by the Climate Center identified no strong trends in Texas’ overall annual precipitation but found a marked upward trend in temperatures. As the summers get hotter, naturally occurring droughts will become more severe.

“Even a very conservative extrapolation,” the assessment said, “would make a typical year around 2036 warmer than all but the five warmest years on record so far.”

“Higher temperatures will lead to unprecedented severe drought impacts,” it said.

Farmers in Texas are looking for ways to cut their losses during drought, said Brant Wilbourn, associate director of commodity and regulatory activities at the Texas Farm Bureau. Practices to boost soil moisture retention can help crops withstand drought conditions.

The practice of leaving crop debris on fields over winter helps retain soil moisture. Cover crops like wheat and rye are also planted in fall and terminated in spring, retaining moisture and providing cover for young crops as they grow.

Abdul Latif Khan, a biotechnology researcher at the University of Houston, searches for secrets of drought tolerance in the dirt itself. Microscopic microbial communities can make big differences during dry spells, he said.But decades of heavy chemical fertilizer, pesticide and herbicide use have left soils badly damaged, leaving plants more vulnerable to dry spells today.

“Poor soil health correlates to lower drought tolerance for crops that grow in it,” Khan said.

Khan’s team has recently experimented with algae additives in the soil of cotton plants, which improve microbial health. They have also identified specific microbes that promote drought tolerance, which Khan plans to patent.

“If you have more microorganisms in soil, you have healthy soil,” Khan said. “This consortium of microorganisms are really helping with drought stress conditions. They are basically improving the defense mechanism of plants to reduce the drought stress impacts.”