It has been common practice for oil and gas drillers to burn off excess natural gas that comes from oil extraction – a practice known as “flaring.” Natural gas is often burned because there isn’t enough pipeline to transport it for processing.

But flaring pollutes the environment and damages public health. Now, regulators in Texas are moving to curb it. Travis Bubenik of Courthouse News told Texas Standard that the Texas Railroad Commission, which regulates fossil fuel extraction, decided Tuesday to change an administrative form oil and gas companies are required to fill out if they want to flare natural gas.

“The changes would involved some things like, you’ve gotta tell the Railroad Commission more details on why you need to flare; you’ve gotta justify it more,” Bubenik said. “The Railroad Commission says that it should incentivize companies to either flare less … or to find ways to not flare.”

Read the full story below from Courthouse News:

Texas regulators on Tuesday moved forward with proposed administrative changes that are expected to become part of a broader effort to tackle the years-long problem of oilfield flaring, where companies burn off excess natural gas into the air.

Before the coronavirus pandemic gutted global oil demand and decimated the U.S. oil industry as a result, high levels of flaring in Texas oilfields had long frustrated environmental groups and even some within the industry.

Though the issue may have become less urgent in recent months as flaring fell alongside massive declines in U.S. oil production, environmental groups remain worried about the longer-term picture, given that flaring activity could still bounce back as the economy and the oil industry recovers.

The practice, where natural gas is burned off because of a lack of pipelines to ship it to market or because of emergencies, causes local air pollution and wastes a valuable energy resource. Some experts have called flaring a “black eye” for the industry.

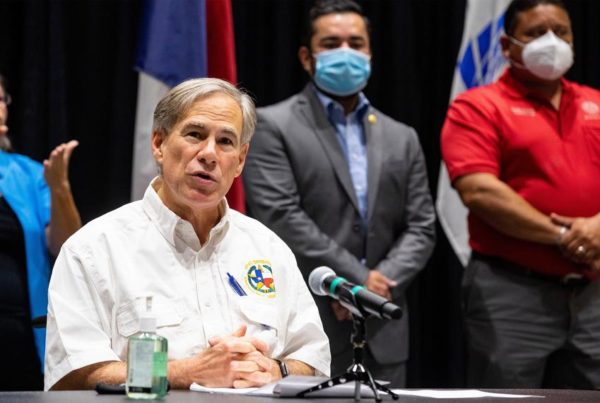

At a virtual meeting Tuesday, regulators with the Texas Railroad Commission — which oversees fossil fuels, not railroads — voted to move forward with proposed changes to an administrative form that companies have to fill out when they want to flare gas beyond what’s typically allowed. The commission plans to take public comments on the proposed changes for 30 days, with a final vote expected later this year.

Under the proposal, companies seeking to flare gas for an extended period of time would face a more detailed application form than the one that’s currently used. Companies would have to offer more thorough justifications for why they need to flare, for starters, while the commission would closely track the locations of where the extended flaring occurs.

At Tuesday’s meeting, one Railroad Commission staffer said the new version of what’s called the statewide rule 32 exception data sheet would lead to less flaring.

“If adopted, the proposed data sheet will reduce the duration of administrative flaring exceptions in many circumstances,” said Paul Dubois, the assistant director for technical permitting within the agency’s oil and gas division.

The proposal stems from recommendations developed at the regulators’ request by a coalition of pro-industry trade groups.

In June, the groups released a report outlining a variety of steps regulators could take to reducing flaring, including measures the report said would “encourage operators to flare less for less total time and to seek and develop alternatives.”

Dubois said the changes to the flaring form would give companies “incentives” to “voluntarily deploy flare-reduction technology.”

Critics remain skeptical about the proposal and responded Tuesday with calls for the Railroad Commission to do more.

The Texas chapter of the Sierra Club slammed the proposal as “lackluster,” noting that the regulators also approved about 30 requests for extended flaring at Tuesday’s meeting at the same time that they moved forward with an effort to reduce flaring.

“Better data and documentation is a good thing, but the commission should listen to companies, the public and legislators calling on a much bolder approach to actually reduce pollution that is impacting communities right here in Texas,” Cyrus Reed, an advocate with the environmental group, said in a statement.

The Sierra Club also pointed to a letter a group of Democratic state lawmakers sent the commission ahead of Tuesday’s meeting, urging the regulators to come up with a plan to “end routine flaring in Texas.”

Colin Leyden, an advocate with the Environmental Defense Fund, described the proposed changes as “limited improvements” but also pushed regulators to take further action. The EDF has worked alongside some in the industry to reduce flaring.

“Industry is quickly moving to a reality where zero routine flaring is the expected operational standard,” he said. “The commission needs to commit to ending routine flaring by 2025, define interim targets, and stop granting long-term flaring exemptions —like the 30 we saw approved today.”

During Tuesday’s meeting, Dubois cited Railroad Commission data showing that flaring activity in Texas has fallen drastically over the past year, but mostly during the pandemic.

From June 2019 to May of this year, the total volume of gas flared across the state fell about 82% percent, Dubois said, while the rate of flaring fell by 79%. The rate is the ratio of gas flared compared to the amount of all gas produced.

Dubois said two-thirds of the drop in flaring rates happened just between February and May.

“The rate of flaring has declined more than the rate of oil and gas production,” he said, cautioning that “the causal factors are not known.”

“The rate of flaring being reduced by 79% is highly significant when you consider at minimum more than one third of the reduction came before the curtailment of production in response to the pandemic,” said Todd Staples, president of the trade group Texas Oil and Gas Association.

Still, the EDF has pointed to more recent evidence from satellite surveys that flaring activity is already on the rise again as oil prices have recovered to a more favorable level.

Last week, analysts at the firm Rystad Energy said flaring levels could rise over the longer-term if the pandemic stalls investments in new pipelines.

“Regardless of the state of West Texas-Mexico exports, we conclude that in a $45-$50 [West Texas oil price] world, there will be a need for new gas takeaway projects from the Permian as early as 2023-2024,” Rystad analyst Artem Abramov said in a research note. “If these projects are not approved early enough, the basin might end up with another period of degradation in local differentials and potentially increased gas flaring.”