From The Texas Tribune:

The Texas Education Agency on Monday released its first public school ratings in three years and despite pandemic interruptions, the number of schools that received the highest rating increased.

This year, 27.9% of 8,451 schools evaluated received an A rating. Another 46.1% received a B, 19.4% received a rating of C and 6.7% received “Not Rated” labels. Not all schools and districts are rated because some are alternative education programs and treatment facilities.

The state agency’s ratings — tied in large part to results of the State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness, or STAAR test — are the latest metrics used to grade how well Texas public schools are performing as students emerge from the worst of the global coronavirus pandemic. Even though students returned to classroom instruction last year, surges in COVID-19 infections both last fall and winter forced some schools to close and revert back to remote instruction.

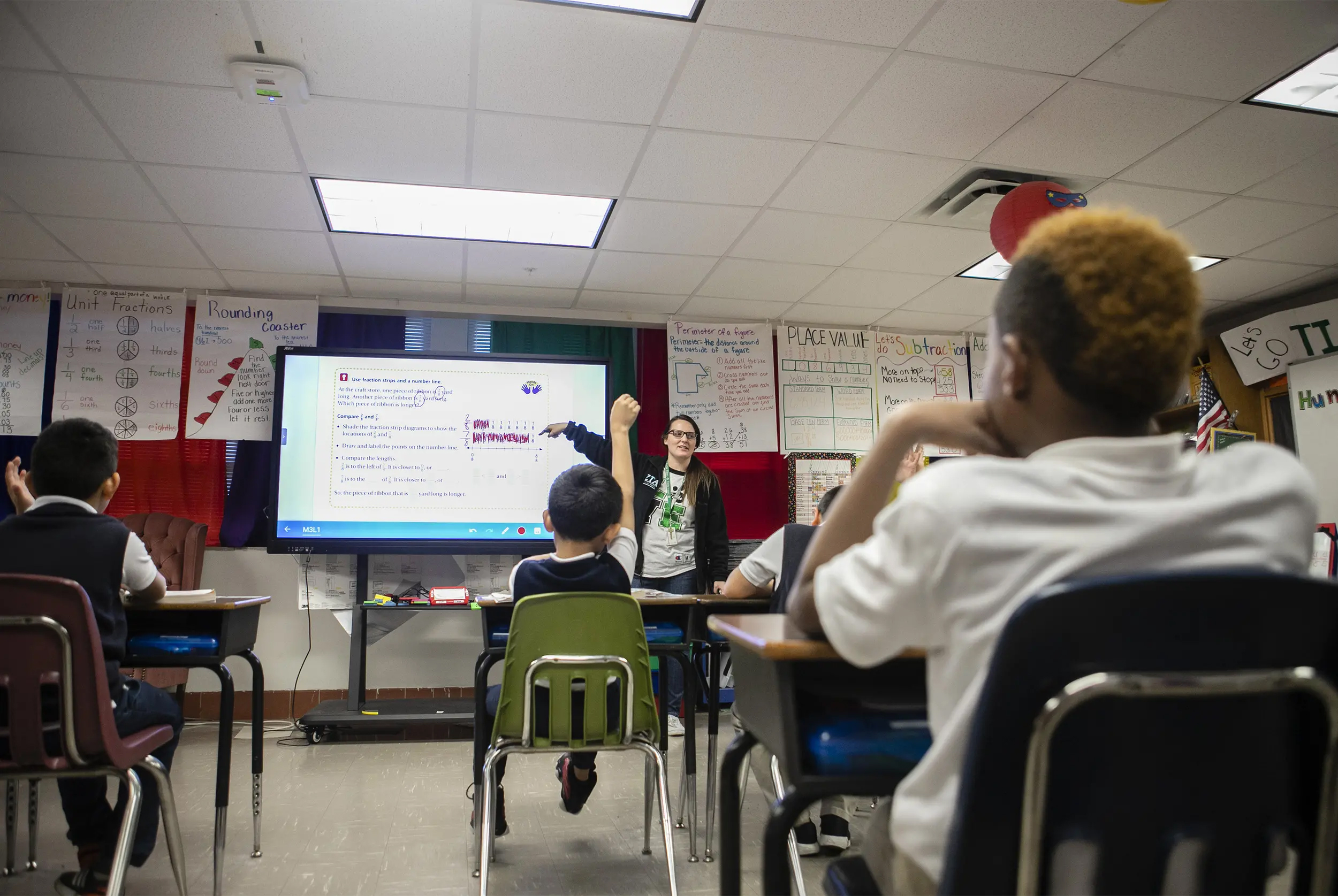

TEA Commissioner Mike Morath credited local educators with the increases seen, despite those interruptions, in each of the A and B categories and a reduction in the number of schools that received below-average grades, those in the “Not Rated” category.

“These results show our state’s significant investment in the post-pandemic academic recovery of Texas public school students is bearing fruit,” Morath said. “I’m grateful for the driving force behind this year’s success: our teachers and local school leaders.”

The TEA’s ratings are determined by scores in three categories: how students perform on the STAAR test, which is given each spring; improvement in those scores; and how well schools are educating disadvantaged students. Students are tested on different subjects: reading, math, science and social students.

Districts also get an overall rating. There are a total of 1,207 school districts in Texas, and 1,195 were evaluated. Out of the districts evaluated, 33.1% got an A, 54% got a B, 9.4% got a C and 3.5% got a “Not Rated” label.

This year’s TEA ratings were done differently than in previous years. Instead of the usual A-F ratings, which were last given in 2019, the agency gave only A-C ratings.

Districts and schools that would have received a D or F instead received a “Not Rated” label this year. Schools that ranked in those bottom tiers will also be spared possible TEA sanctions during the 2022-2023 school year. Families can find their school’s accountability ratings at TXschools.gov.

In 2019, the last time that TEA put out these ratings, 8,302 schools were rated, and 21.1% received an A, 39.5% received a B, 26.1% received a C and 13.3% received failing grades. In 2019, 1,189 districts were rated. Of those, 25.3% received an A, 56.9% received a B, 13% received a C and 4.8% received failing grades.

Texas continues to show some struggle with getting “high-poverty” schools an A grade. Data shows that only 18% of those campuses in Texas were rated an A. The TEA labels schools as “high-poverty” if their number of economically disadvantaged students surpasses 80%. Of the schools that received a “Not Rated” label, over half of them were “high-poverty” schools.

Texas has about 5.4 million students in its public schools, and 60% of them are economically disadvantaged, meaning they qualify for free or reduced lunch. Out of the 8,451 schools rated this year, 564 campuses received the “Not Rated” label. Most of these “Not Rated” campuses — 499 — serve students who live in some of the state’s poorest communities.

While there is work to be done with Texas’ poorer schools, Morath said, the increase among the A-rated schools — a rise seen after the pandemic interrupted classroom instruction — means the state is on the right track to catch students up to pre-pandemic levels.

This spring’s STAAR results showed big gains in reading. While math scores did increase from the dips seen in 2021, they revealed that Texas students still have work to do to catch up to their pre-pandemic test score levels.

State officials say the ratings help parents decide on a school or a district and help hold those districts accountable to parents and taxpayers. Opponents of the system say it harms schools that serve poor communities as they usually get the failing grades and face potential state sanctions such as getting shut down.

Matthew Gutierrez, superintendent of the Seguin Independent School District, received a “Not Rated” label for his district even though more than half of his campuses received a C or above, as his district faltered on other criteria.

Gutierrez believes what hurt his district is that during the pandemic there was a decrease in the number of kids going to college, pursuing technical careers or joining the military. Because of the spread of COVID-19 infections since 2019, the number of students who took the ACT or SAT or attained industry certifications or dual credit decreased, he said.

“I’m really disheartened about the overall district grading,” Gutierrez said. “It’s a very complex, complicated system. I feel like the overall score does not reflect the progress made as a school district.”

The Seguin district also had two middle schools that received “Not Rated” labels, and both of them are majority Hispanic and the number of students who are economically disadvantaged is higher than the state average. But Gutierrez is hopeful that these two campuses will soon improve like his district’s other schools did that have a higher average of low-income students.