From KERA News:

Jamie Wright didn’t know that what was happening to her as a little girl was wrong.

“I thought that everybody was touched, and I thought that everybody’s mom screamed out for help,” Wright said.

No one taught Wright that she deserved better until she was an adult. But today, there are educators who are having that conversation with children in their classrooms.

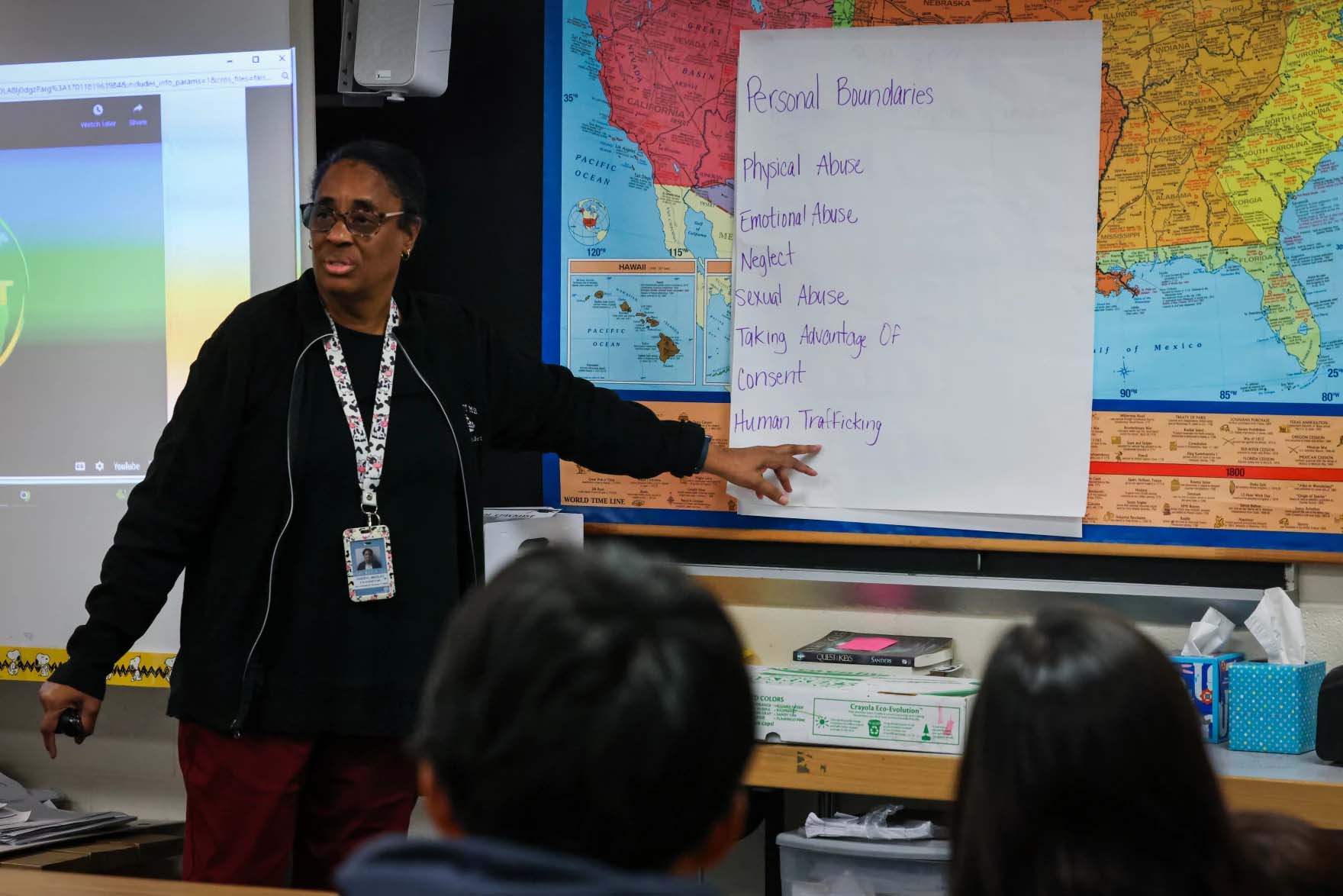

Laura Norman’s classroom at Daggett Middle School in Fort Worth is covered in laminated American history posters. But her students didn’t learn about the revolutionary war or the Alamo last Tuesday. The school counselors, Cheryl Wesley and Theresa Ortiz, taught a lesson about abuse and healthy relationships instead.

Some Texas students learn about forms of abuse in school — but they need their parents’ permission to hear the lesson. Advocates say that requirement is an obstacle that does more harm than good.

Opt-in barrier

The counselors at Daggett Middle School outlined the different types of abuse in their presentation — physical, emotional, neglect and sexual. They also talked about listening to their inner voice.

“It is important to recognize and trust ourselves when something doesn’t feel right,” Wesley said.

The program for the middle school students is titled “protecting a masterpiece.” Angela Hicks, the director of elementary student engagement for Fort Worth Independent School District, said the program is geared toward the middle school age group. The district also has similar trainings for other age groups.

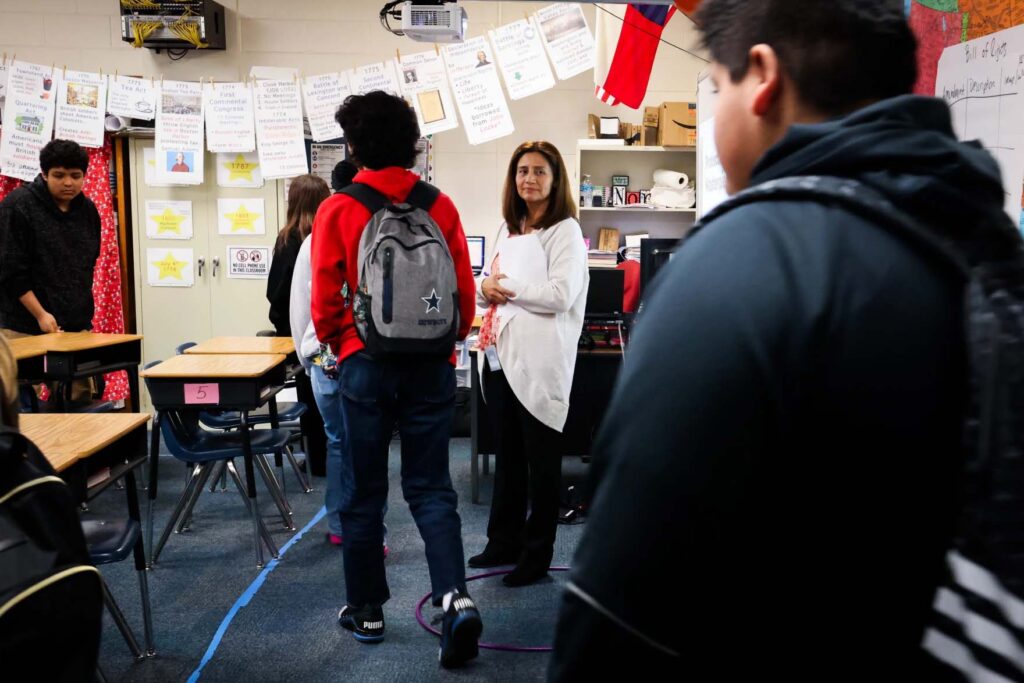

Students chat during an exercise at the abuse prevention training at Daggett Middle School Tuesday in Fort Worth. The class is a two-part program taught by the school’s counselors.

Yfat Yossifor / KERA

A few of the kids in Norman’s class were sent to the library before the counselors started their presentation. Students need written parental consent to get abuse prevention education under Texas law — and those kids’ parents didn’t give theirs.

Molly Voyles, the public policy director for the Texas Council on Family Violence, said the state doesn’t mandate schools to educate students about abuse. Voyles said requiring parental consent makes districts less likely to do it. She said that can be harmful.

“When you create parental opt ins or opt outs, it’s most likely to impact the children with the highest vulnerability,” Voyles said.

Hicks said the parental consent requirement has been challenging. She said over half of the perpetrators of child abuse and trafficking are related to their victims.

More parents in Fort Worth ISD are opting in for the education. Last year, Hicks said 10,000 students were allowed to participate in the abuse prevention training. This year more than three times than that participated. Hicks said that’s about half of the students in the district. She said parents are seeing the difference abuse prevention makes.

“Obviously, they feel like it is a good program and that they do want their students to learn skills in order to keep themselves safe,” Hicks said.

Safety net

The abuse prevention training can still make a difference for the kids who don’t hear the lesson.

Christina Galanis is the director of secondary student engagement for Fort Worth Independent School District. She said the students who don’t hear the lesson have a safety net because their friends and classmates learned about healthy relationships and abuse.

“It still protects those that don’t have that knowledge, because they may lean on a peer or confide in a peer. So it gives that herd immunity kind of mentality,” Galanis said.

Students walk into class for a two-part abuse prevention training at Daggett Middle School in Fort Worth.

Yfat Yossifor / KERA

Wright said that made a difference for her as a little girl. Her sister confided in a friend about the abuse when they were young. The friend knew that the abuse wasn’t ok and told her parents, who told the school.

The abuse was no longer a secret. But Wright still faced challenges because of it. She dropped of junior high school and got pregnant at age 14 by a man who was twice her age. Wright said she would’ve had healthier relationships growing up if she had the right tools.

“You can’t tell me that if somebody had taught me that, especially in my formative years, that I’d be navigating life in this hard space that I’m in right now,” Wright said.

Today, Wright shares her story about how she survived domestic violence as a child and adult to give others the voice she didn’t have.

Language makes a difference. William West, a prevention manager at the Texas Council on Family Violence, said giving kids the words to describe the harm they’re going through empowers them to seek help for the rest of their lives.

He said that’s why teaching young people about the signs of abuse is essential for building community resilience.

“When you can have that education, it works to break intergenerational cycles,” West said. “It works to increase health seeking behaviors. It works to decrease isolation.”

And all of that starts when students learn about it at school in a classroom like Ms. Norman’s at Daggett Middle School.

It’s a lesson the Texas Council on Family Violence said every student in the state should learn. But for now, school districts don’t have to teach it. And the districts that do teach it have to ask for parents’ permission.