From Texas Public Radio:

Every year, the state of Texas goes to court and asks a judge to free it from the responsibility of caring for dozens of foster kids who are missing or runaways.

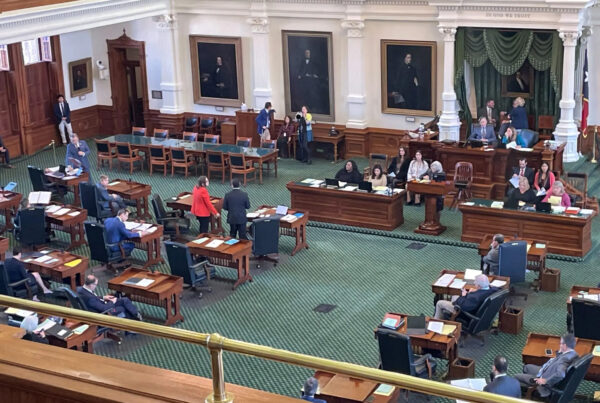

“It’s just unacceptable that when a child or youth run away that we would then wash our hands of responsibility,” said Texas House Member Gina Hinojosa. The Austin Democrat filed a bill to stop the practice.

“These are our children. And just because they run away … it puts them in more danger. It makes them more vulnerable,” she said.

The Department of Family and Protective Services said they can’t tell us why they closed 40 missing minor cases in 2021, the last year they have released data for. It’s confidential.

But some former CPS workers, parents and lawyers TPR spoke with have suggested the department drops or “nonsuits” missing kids to limit its legal liability or to better use resources to serve kids still in care.

“I believe that it has to do with liability,” said Jenifer Knigton, whose daughter was under child protective service custody last year. “When a child is on runaway status, you know, a lot of things can happen to them. And it’s a liability for the state.”

Knighton has a fraught relationship with DFPS. Her daughter ended up in the juvenile justice system for a crime. Knighton said her addiction to methamphetamines was out of control, and she struggled to find help for her or to get the state involved. The state took custody of her daughter when she got out of juvenile detention, but they didn’t have a home to place her in.

She was put up in a hotel — joining dozens and sometimes hundreds of others of children without placement on a given night, referred to as CWOP (Child Without Placement) kids. These unlicensed placements staffed by CPS workers have been the focus of federal hearings who say the practice is dangerous with kids being assaulted by hotel staff, and engaging in dangerous behaviors such as sex and drug use.

“She ran away. She was picked up probably about a week later. She was severely intoxicated,” said Knighton. “She was released from the hospital while she was intoxicated and my kid went missing for three months.”

But instead of looking for her — Knighton said — after a few months, the state went to court to terminate its relationship with the girl. Before long, her daughter was being trafficked for sex.

Sexual abuse and trafficking are common outcomes for missing and runaway youth in Texas’ foster care system. According to state data, 132 youth reported being sexually victimized while missing, or about 6 percent of the total recovered that year.

“They just non-suited it and…They gave me custody back of my missing kid,” she said.

Ultimately Knighton would get her daughter back and she got her into treatment. And this time, her daughter didn’t run from it.

DFPS declined to discuss the case.

Knighton had turned to a nonprofit group called the Texas Counter-Trafficking Initiative to help find her daughter.

The group of unpaid-volunteers spend time tracking sex ads online and attempting to assist law enforcement in recovering girls being trafficked.

JB Rice, the group’s executive director, helped recover Knighton’s daughter after finding ads of her online.

In the middle of the night on a recent Friday, the 50-something year-old man drove a stretch of one of Houston’s open air sex markets near the corner of Bissonnet and Plainfield.

He stared into the small groups of women working the track one Friday night, scanning it for two teenagers who he’s found sex ads for online.

“I don’t think she’s big enough…Like I said, it’s hard with makeup,” said Rice, motioning to one petite woman.

“If you don’t see a girl made up to work and in the [missing child] photos, there’s no makeup, he said. “And then they come out here, they got on the eyelashes and a ton of war paint, sometimes it’s difficult to make a good ID.”

In this case, he knows one of the 13-year-old girls was recently given a large chest tattoo.

Mostly he searches online and tries to identify hotels since most minor girls aren’t put on the street to work, but that night he had little information and took a chance.

“They’re often wearing less than you would see on them in a strip club,” he said.

Cars slowed to drive by the women, who wore almost nothing — G-strings and heels and small bikinis. Sometimes the women pulled on door handles of cars just passing. Other cars stopped to attempt to purchase services.

If he spots a girl, he calls police and tries to get them to recover the girl.

But after a couple hours of driving, the only progress he made was slowly filling a small water bottle with the dark liquid remains of his chewing tobacco. This is how many nights end for him.

“If I don’t see our girls between here and that stop sign, we’re gonna hit airline,” he said, referring to another street known for its sex workers.

At his office, six of the seven girls on his office board were in DFPS custody. They are girls who few would be looking for at all if he wasn’t.

For Hinojosa the lack of resources to provide police with the time to do this work needs to change.

“This is a well resourced state, and I am frustrated that when it comes to our kids and especially our most vulnerable kids, we are under-resourced,” she said.

For now, her bill only makes it more difficult if not impossible for the state to ‘‘wash its hands” of missing and runaway kids.