Tamir Kalifa is being recognized for his coverage of communities affected by gun violence, including in Uvalde, where he documented community mourning and mobilization efforts after the 2022 Robb Elementary School shooting.

Kalifa’s freelance work has been featured in the New York Times, the Washington Post and Texas Monthly, among other publications. And now he’s been awarded the American Mosaic Journalism Prize from the Heising Simons Foundation.

The California-based family foundation is focused on research in science education, the climate and human rights. Its photojournalism prize is awarded for excellence in covering stories about underrepresented and or misrepresented groups in America.

Kalifa spoke with the Standard on what this award means for him and what it means to him to represent life through his photos. Listen to the interview above or read the transcript below.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: I mentioned you’re abroad right now. How did you hear you’d won this award?

Tamir Kalifa: So I was in Israel visiting family at the beginning of October when the war started and I’ve been covering it pretty much ever since. Someone reached out to me from the foundation, which just came as such a profound shock. It’s not something that I applied for, but it’s a profound honor to be recognized for this work. But also because it allows me to continue talking about Uvalde and talking about the importance of this kind of personal, intimate, empathetic journalism and storytelling.

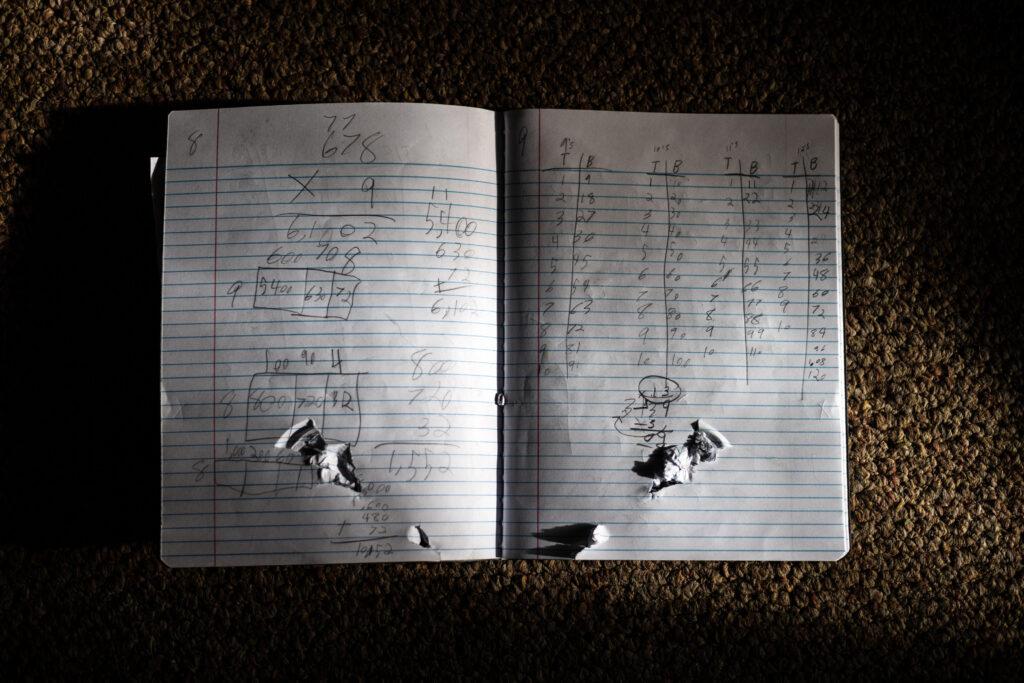

10-year-old Uziyah Garcia’s math notebook, which was closed when it was struck by a bullet during the mass shooting at Robb Elementary School, is seen in Uvalde, Tex., on June 1, 2022. Uziyah was among the 19 children and two teachers killed in the shooting.

What drew you to cover Uvalde in the first place? What were you hoping to bring to the story when you went down there?

So I’d covered gun violence previously. I spent three months in El Paso with a family that survived the Walmart shooting. I’ll never forget that when I left El Paso, I felt like the work, the story and the experience of the Calvillo family was really just beginning and that there was so much more that needed to be done.

And so, almost the day I arrived in Uvalde, which was less than 24 hours after the shooting, I just felt really compelled to stay there with it and to try to help Texans and Americans grasp the consequences of gun violence from up close.

What are you looking for through that lens?

I’m trying to be just a medium between strangers and the people that I’m with. I just want the public to see themselves in these individuals before the camera who have so kindly and openly allowed for me to document their experience, which is not something that I take for granted. They are trusting me to help convey their experience to the public in order to help them better grasp the consequences of gun violence from up close.

And so, what I’m looking for in a photograph is something that can help invoke empathy from strangers and something that can help the public see themselves in these people. That could be anything from a father in his daughter’s bedroom to a family going shopping to driving in a pickup truck down Main Street in Uvalde. Just something that is so personal and so relatable that a stranger reading this can’t help but think, “My God, that could have been me.”

Javier Cazares speaks to his daughter, Jackie, 9, in her bedroom in Uvalde, Texas, before going to sleep on June 13, 2022. Jackie was among the 19 children and two teachers killed in the shooting at Robb Elementary School. She loved her family and friends and had dreams of one day visiting Paris.

I would think that you, as a journalist, sort of want to be invisible, but your presence is inevitable. Does that become a factor in your reporting?

It’s true. I mean, there’s no such thing as being a fly on the wall in these kinds of places and the reality is that any photographer, any journalist or member of the media will inevitably affect the kind of space that they’re in.

And so what I’ve learned is that by building these relationships and by exercising this care and getting to know these individuals, like those in Uvalde, it’s the trust that they have in me that allows for me to be present with them and make these photographs that speak to this vulnerability and this grief and this pain.

But they are willing to share that with me, I think, because it’s not the only thing that I’m after. I firmly believe that we must see the darkness in order to appreciate the light and one can see these images of profound grief and see those same people enjoying the company of their family and the company of their friends, even as they’re still struggling to make sense of all of this and these and still feeling grief.

And something that I learned in Uvalde and in El Paso is that sometimes you also have to be prepared to not make a picture and that there are moments that just belong to those families. It truly is a privilege for me to be in those spaces and those moments. And sometimes it’s better to just put the camera down and give someone a hug.

Caitlyne Gonzales, 11, who lost many of her friends in the shooting, sings and dances to Taylor Swift songs at her best friend Jackie’s grave in Uvalde, Tex., on April 19, 2023.

You’re now reporting from Israel, covering the war there. How is this experience different from your previous work, or is it that different?

I think that there are a lot of similarities, in part because grief is something that affects all humans and it affects them all in different ways, but the source of it is just this profound and unimaginable loss, whether it’s from gun violence or through violence of any kind.

So that grief must be respected and I also think centered, because if we are to grasp what is happening in these places then it really requires reckoning with the human toll that this conflict is taking.

How do you make a choice about which stories you want to cover?

Sometimes it feels like it chooses me in a way because of my proximity to it. A lot of times I’ll be assigned to cover a story and I was assigned to document the aftermath in Uvalde. But it got to a certain point where I think the media cycles begin to shift elsewhere and attention starts to shift and so at that point, it becomes a choice and not as much of an assignment. And that’s what happened in Uvalde.

I felt, as I got to know this community and as I reflected on the work that I’d done on the subject of gun violence, I felt increasingly inclined to try to dig deeper and try to make something meaningful. I even moved there. I moved to Uvalde from March to May. I lived in a little shipping container that was turned into a tiny home just so I could be there.

Sometimes some of the families decided that they’d get a tattoo right then and there, or that they’d go to the cemetery then and there. And I just wanted to be there for when they were ready to have me.

So this award and this recognition allows me not only to keep working in Uvalde, which I’ve decided is going to be a lifelong project and pursuit, because I think that I have so much more to learn from these amazing families, and I think the public does as well.

I think what’s most meaningful about this award is that it’s also recognizing a certain kind of journalism and a certain kind of storytelling and it’s one that really centers individuals and families and communities and looks at their experience over time in a way that’s empathetic and compassionate. And I think that kind of work has a very important place in our public discourse and in the media and it’s really one of the greatest honors I could have possibly hoped for and imagined.

If you found the reporting above valuable, please consider making a donation to support it here. Your gift helps pay for everything you find on texasstandard.org and KUT.org. Thanks for donating today.