From Marfa Public Radio:

This story was reported and produced in collaboration with Martha Pskowski, a reporter at Inside Climate News. This is the second story in a three-part series on the town of Toyah and the water issues that have plagued the community for years. To hear the first story, click here.

The question of whether to drink the water or not in Toyah is a hot-button issue.

Reports of rancid water flowing out of taps contrast with city officials claiming the water is safe. Still, the dwindling West Texas community, about 20 miles west of Pecos, has also been on a boil water notice for nearly five years.

Despite the problems in Toyah, Olga Lopez dreams of moving back to her hometown to spend her golden years. Standing in her family’s home near the train tracks, memories of her childhood come flooding back to her.

“I look out here and I can see where we had our pigs and the chickens roaming around freely,” Lopez said. “Why can’t I have that now? One thing, the water.”

Lopez takes the boil water notice seriously, but she doesn’t want to stay away too long. She has plans to raise her own chickens here someday. She’s even bought a large tank to haul in water if things aren’t cleared up soon.

Some residents worry that the water may be so hazardous that it may not be safe to bathe in. There have been reports of rashes and serious bacterial infections people believe are the result of coming into contact with the water.

“I want to be able to come over here maybe on the weekend, and make me a fresh pot of coffee and sit outside and, and reminisce,” she explained.

Her parents have passed away, so this place is important to her. Looking around her property, thinking about the future she could have if the water were safe, she said, “Doesn’t hurt to dream, right.”

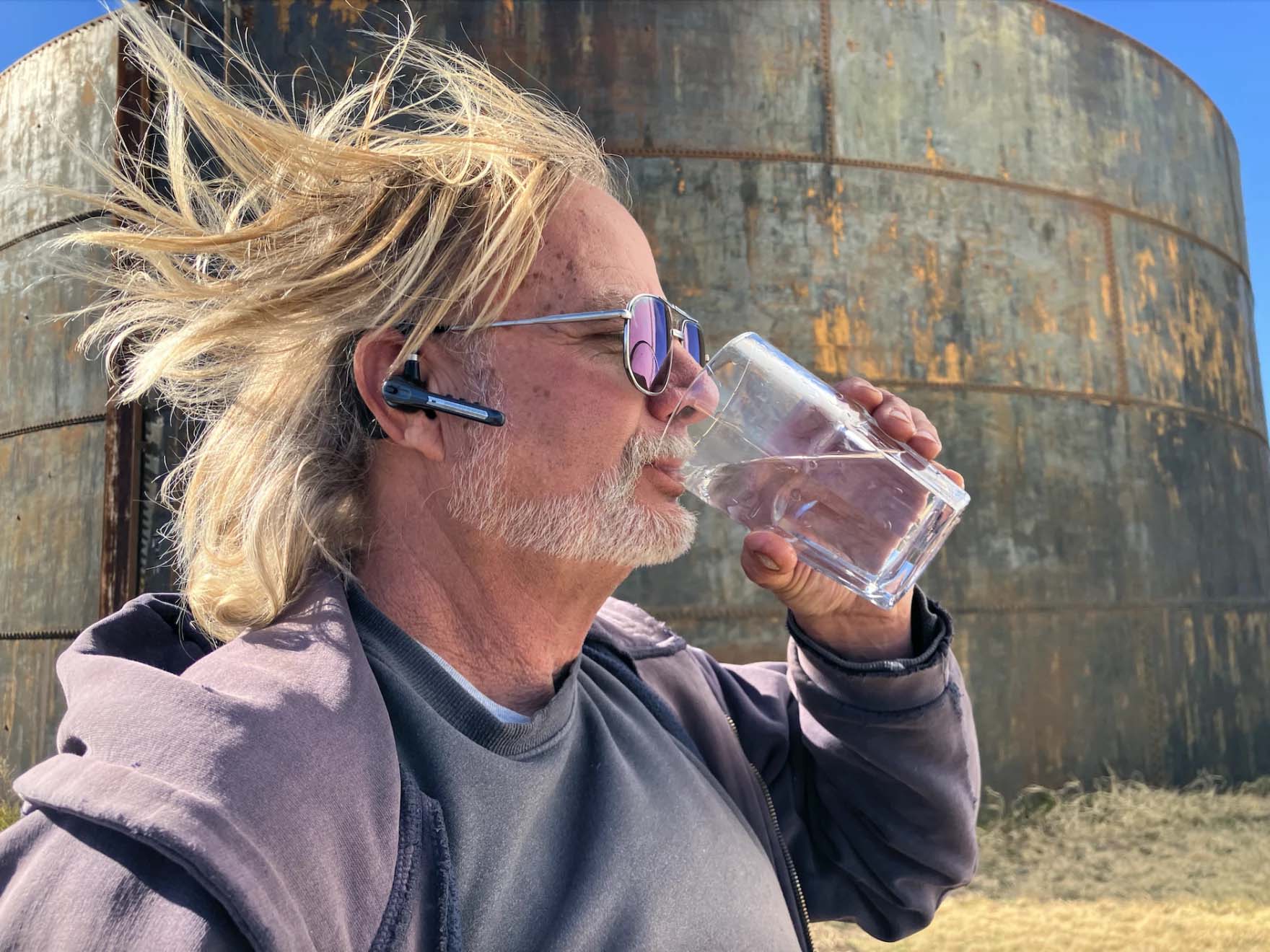

The home Olga Lopez hopes to retire to in Toyah sometime soon.

Mitch Borden / Marfa Public Radio

Late last year, the Texas Attorney General’s office filed a lawsuit against Toyah to take over the city’s water system. Court documents cite concerns over mismanagement and list over 30 violations of state drinking water rules.

While the lawsuit moves through the courts, the city is still in control of its water. At this time, 70-year-old Ed Puckett is helping run Toyah’s water treatment plant. He’s a retired contractor who volunteers his time to keep the city’s water running.

“I want you to come see the plant,” Puckett told me over the phone. “I want you to understand this is not amateur hour.”

While touring the facility, he pointed out how Toyah’s water is cleaned and sanitized.

Puckett said the city’s water problems — reports of discolored water and noxious smells coming from water taps — are a thing of the past. Claiming one of the only problems right now is the water is sometimes “too clean.”

The state of the treatment plant is a stark comparison to his description though. The building is shabby. Its thin metal walls bang with every gust of wind. There are holes in the building where animals can get in and hanging electrical wires — but Puckett keeps up his pitch.

Pointing out a meter that measures the cloudiness of water, he said, “This is almost pure, it’s really, really close.” The meter showed the water was just barely meeting state standards.

Toyah gets its water from a spring miles away that bubbles up in a cow pasture. Cattle and other wildlife have access to the stream before it travels to the treatment plant — making it really important it is cleaned properly.

To prove it’s safe, Puckett walks outside to pour a glass right from a tank. “It tastes good too,” he said with a smile.

This illegal water filter was used by the community for years while parts of Toyah’s water treatment plant were inoperable.

Mitch Borden / Marfa Public Radio

There has been a long list of issues facing the facility and the town, which Puckett doesn’t deny. For years, the facility’s filtration unit didn’t work properly, forcing the community to use an illegal filter. At times city staff had to pour gallons of bleach into the drinking water to sanitize it because chlorine levels were so low.

According to Puckett, the cause of most of the city’s problems was a series of pipes that had been hidden for years.

“This had more to do with the quality of our drinking water in the last 15 years than anything else,” he said, pointing to a patch of dirt where the pipes were buried.

In 2021, a buried cross-connection was discovered — it had been funneling untreated water into the town’s clean drinking water.

Puckett explained, “When we found this and took out all of this section of pipe, the quality of our water improved 1,000%.”

Toyah’s current water operator, Brandie Baker, didn’t want to be interviewed for this story. But Puckett said she’s the “most qualified water operator” the town has ever had.

Baker does not have the proper license to run Toyah’s water system, which locals and state regulators have raised as a concern. Since 2018, the state has required Toyah to have a Class B Surface Water Operator, but Baker has failed that licensing exam twice.

Still, Puckett is convinced if she can pass that one test, Toyah’s water will be recognized as safe to drink by regulators. According to him, “We fixed everything that is broken, and we are producing beautiful water. Now we have to fix the bureaucracy part of this and get us off the boil notice.”

At least two qualified water operators have offered their services to Toyah over the years, but local leaders continue to trust Baker and Puckett to run its water system. Puckett bristles at the thought of the state coming in to take over the treatment plant.

“You’ve seen it, it’s working. We’re making good water. If you know, there’s hardly anything that needs to be done at this point,” he said.

At 93, Loretta Campos is the oldest person in Toyah and proudly drinks its water in spite of the boil water notice.

Mitch Borden / Marfa Public Radio

Some very vocal residents disagree and are very concerned Toyah’s water may still pose a health risk. A large swath of the town however continues to drink local water.

“I don’t see anything wrong with the water,” said Loretta Campos. “I really don’t know what this is all about. “

Toyah’s population is less than 100, and at 93 years old, Campos is the oldest person in the town. The water here has always been one of her favorite things.

“We have very good water, actually sweet, very sweet,” she described.

Despite the boil water notice, she’s continued to use local water. She said, she doesn’t think about the presence of dangerous bacteria or other contaminants — if the water is clear she’s not concerned.

Campos said, “I just drink it and, and that’s it. I don’t think about it. Maybe I’m trusting too much, but I don’t have any problems.”

If there was something to worry about, she believes someone she could trust would have told her. Still, people are working right now to get Toyah reliable safe drinking water, whether Campos and other residents like it or not.

Locals, lawyers and even college students have been diligently advocating to get regulators more involved in the small town while also looking for long-term solutions.

More on that next week, in Marfa Public Radio’s final installment of this series looking at Toyah’s water issues.