From KUT:

It was outside the mailroom where Deborah Michals learned she could lose her home.

One night this past summer when Michals walked outside her condominium in North Austin to check her mail or catch up with a neighbor doing laundry — she can’t remember which — she noticed a man she didn’t recognize. He told her he’d moved into the condo above hers.

“Let me know if there’s anything I can do to help,” Michals remembers telling him. “I’ve been here awhile.”

Michals and her husband bought their one-bedroom home in 2018. They were the first to purchase a condo in a 14-unit apartment complex that had been redeveloped. At less than $200,000, the 600-square-foot home felt like a steal in Austin’s pricey housing market, and the monthly mortgage was something they could afford in retirement.

The location, though, was what ultimately sold them. The condo is about two miles from the UT Austin football stadium, and the Michalses are big college sports fans. They spend about six months out of the year at their condo in Austin and the rest of the time at a home they own in Waco.

Deborah and Dean Michals prepare to leave for a UT Austin basketball game in their condo in Austin on Jan. 11.

Michael Minasi / KUT

So, Michals wanted her new neighbor to feel as wonderful as she did about living on East 52nd Street. But Trevor Titman didn’t plan on staying long, he said. He was an investor who had bought three other units.

“Eventually I want to sell to a developer,” Michals remembers him saying. (Titman told KUT he doesn’t recall this conversation, but another neighbor who was present at the time agreed with the general characterization of it.)

She told him, well, good luck — I’m not selling. As Michals remembers it, Titman turned to her and said she could be forced to sell.

Michals figured he was posturing. She shrugged off the comment and walked away. But days later, she wondered: Was he right? Could she have to sell? A retired school teacher, Michals dug into state law and the documents she was handed when she bought the condo.

It turned out, she could.

In Texas, condo owners can be forced to sell their homes. A state law passed three decades ago allows the sale of a condo complex to go ahead with just 80% of the complex in agreement; each condo typically gets a vote proportional to its size. Once the deal is final, any remaining objectors have to sell their homes.

Those who support the law say it makes financial sense. Owners living in aging buildings with little funds for repairs can get out and benefit greatly when splitting the sale of an entire complex. But many condo owners who spoke to KUT were unaware of the rule until their neighbors began pondering a sale — and some say the law pushed them out of their homes.

A balancing act

Michals’ predicament is specific to condo owners, and it illustrates how complicated this type of homeownership can be.

A condo is an apartment you can buy. Unlike a single-family home or a townhouse where ownership is typically outright, condo owners share walls and sometimes common spaces, making ownership knotty.

“If you own a condominium, you own the part of the unit in which you can walk,” said David Kahne, a condo lawyer based in Houston. “Sit, eat, sleep, the part that you use.”

Then there are the spaces owners collectively control, such as a pool, the laundry room and the exterior of the building. Repairs to these areas are typically financed with a monthly homeowners association fee.

Condos gained popularity in the U.S. in the 1960s. As the federal government started backing mortgages for condos, states began regulating them. In 1963, Texas adopted the Texas Condominium Act, which defined and established the existence of condos.

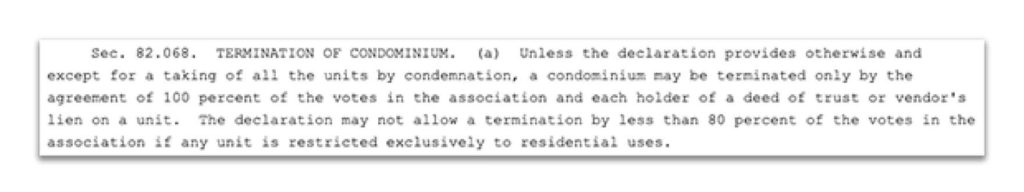

State lawmakers eventually overhauled the law in 1993, adopting the Texas Uniform Condominium Act. House Bill 156 included a brief provision: In order to sell a building, 100% of condo owners needed to agree to a sale. But the state would allow homeowners associations to adopt a rule saying a building could be sold with a lower threshold — just 80% of owners.

The portion of Texas law that states homeowners associations can adopt a ruling allowing a sale to go ahead with the agreement of at least 80% of owners in a condo complex.

Former state Rep. Robert Eckels, R-Houston, who worked on the bill, said he doesn’t remember the provision being controversial. (Another Republican who authored the bill, Sen. John Carona, did not respond to a request for comment.)

“You need to understand what you’re buying,” Eckels, who retired from the legislature in 1995, told KUT. “Usually when you’re buying a condominium property you get a disclosure of all this information. But most folks don’t read it.”

Backing a clause that could force people to sell their homes may seem out of place in a state like Texas, where the rights of private property owners are often glorified. But former state Rep. Will Hartnett, R-Dallas, said this part of the law makes business sense.

“The legislature would never allow one person to block the sale or redevelopment of an entire property,” Hartnett, who retired from the Texas Legislature in 2013, told KUT. “You’ve got the monetary interest of the majority versus the sentimental or personal or rooted interest of the minority. That’s the balancing act.”

Oracle buys a condo complex

Titman purchased four units in the building on East 52nd Street in 2021. He told KUT he figured land values in Northeast Austin were on the rise, and he might be able to cash out soon. Titman also bought the land next door, where a daycare center currently operates.

“I saw that these [condos] downtown had been bought out, and I thought it was just a matter of time that things in this area of Austin would appreciate to the point where the same thing would happen,” he said.

Titman said he has talked with developers about purchasing the complex, but none have put together an offer. He said he believes if it went to a vote right now, 80% of the 14 owners would vote to sell.

If that happens, unwilling residents, like Michals, would be forced to sell. It wouldn’t be the first time this situation has played out in Austin.

Valerie Strauss bought a two-bedroom condo off East Riverside Drive in 2007. She had recently gotten divorced and was looking for a place she could afford close to her daughter’s school. Strauss, who works at the Capitol, said she loved living so close to downtown.

“It took me eight minutes to get to work in the morning in my car,” she said. “I was on the boardwalk every single day with my dog, with my girlfriends, walking downtown for dinner and movies. … That was my lifestyle.”

In 2018, the homeowners association at Town Lake Village Condos began entertaining offers to purchase the property — including at least one from Oracle. The technology corporation, according to one condo owner, was looking to expand its headquarters along the waterfront. (Oracle did not respond to a request for comment.)

In 2021, Oracle purchased a condo complex near its headquarters. It’s unclear what the company’s plans are, but it has started an application to demolish the buildings.

Michael Minasi / KUT

Years went by, though, before the board of the homeowners association received an offer from Oracle they decided was worth taking to all the owners in the 74-unit building. A contentious fight followed, according to several people involved, pitting neighbor against neighbor.

While Strauss had known about the possibility of fewer than 100% of owners forcing a sale for years, she said at the time she bought her home she had no idea it could come to this point.

“I had never heard of that [law] and wasn’t ever thinking of that as a possibility,” she said.

In late 2021, the owners took a vote. Oracle reportedly offered more than $43 million. Just over 80% of condo owners agreed to the sale, meaning the rest would have to sell against their wishes. The sale was finalized just before the new year. When it was all said and done, owners received somewhere in the ballpark of $500,000 per unit, depending on the size and condition, and Oracle gave them the chance to stay in their homes for a year, rent free.

Sarah Wimer stayed for the last year, but said she was “completely distraught” over the sale. The 71-year-old bought a two-bedroom condo in the building in 2014 for $185,000, and she made it her own, painting the bathroom hot pink and the living room lime green.

Like Strauss, she loved being able to walk or take a bus wherever she needed to go: “I’m ecstatic about not owning a car.”

Oracle bought a complex of condos on Tinnin Ford Road in 2021. Just over 80% of owners agreed to the sale.

Michael Minasi / KUT

Wimer estimates that after using the money to pay off her mortgage, she pocketed about $370,000 in the sale, which helped her secure a two-bedroom apartment nearby. While she pays $2,600 a month in rent — which is more than double her monthly mortgage payment — she said she loves the natural light of her new home.

“Being forced to move gives me an opportunity to do more decorating,” she said.

Strauss left the city entirely and bought a house in Lockhart. While she said she has grown to love living outside the city, she said Oracle’s offer did not give sellers the option to replicate the lives they’d been living.

“We certainly didn’t get replacement value,” Strauss said. The neighborhoods surrounding East Riverside Drive have changed dramatically over the past decade, and homes in the area typically go for $454,000. “None of us bought condos on the lake.”

Condos tend to be cheaper

Just 4% of people in the Austin metro area who own their homes and live in them are condo owners. But while that number is small, it represents a nearly four-fold increase over the past two decades.

Condos may be more popular as the prices of single-family homes have skyrocketed in Austin in past years. Last year, condos in the Austin metro sold at prices 18% less than single-family homes. This is likely because condos tend to be smaller than single-family homes and don’t typically have a lawn.