This story originally appeared on Houston Public Media.

When I’m at an art museum, I never know what piece will catch my eye.

On this particular visit to the University of Houston’s Blaffer Art Museum, it’s an art installation by Matthew Buckingham. It consists of is a 16-millimeter film projector on a pedestal, projecting a flickering black and white image of the numbers “1720” on a small screen suspended in mid-air. The music coming from the projector is a Baroque flute sonata by Bach.

So, if someone could look into my head at this moment and see what’s going on in my brain, would they be able to see that I like what I’m looking at?

Dr. Jose Luis Contreras-Vidal, (better known as “Pepe”) is in the process of finding out. The University of Houston College of Engineering professor is collecting neural data from thousands of people while they engage in creative activities, whether it’s dancing, playing music, making art, or, in my case, viewing it.

“(The hypothesis is) that there will be brain patterns associated with aesthetic preference that are recruited when you perceive art and make a judgement about art,” Contreras-Vidal says.

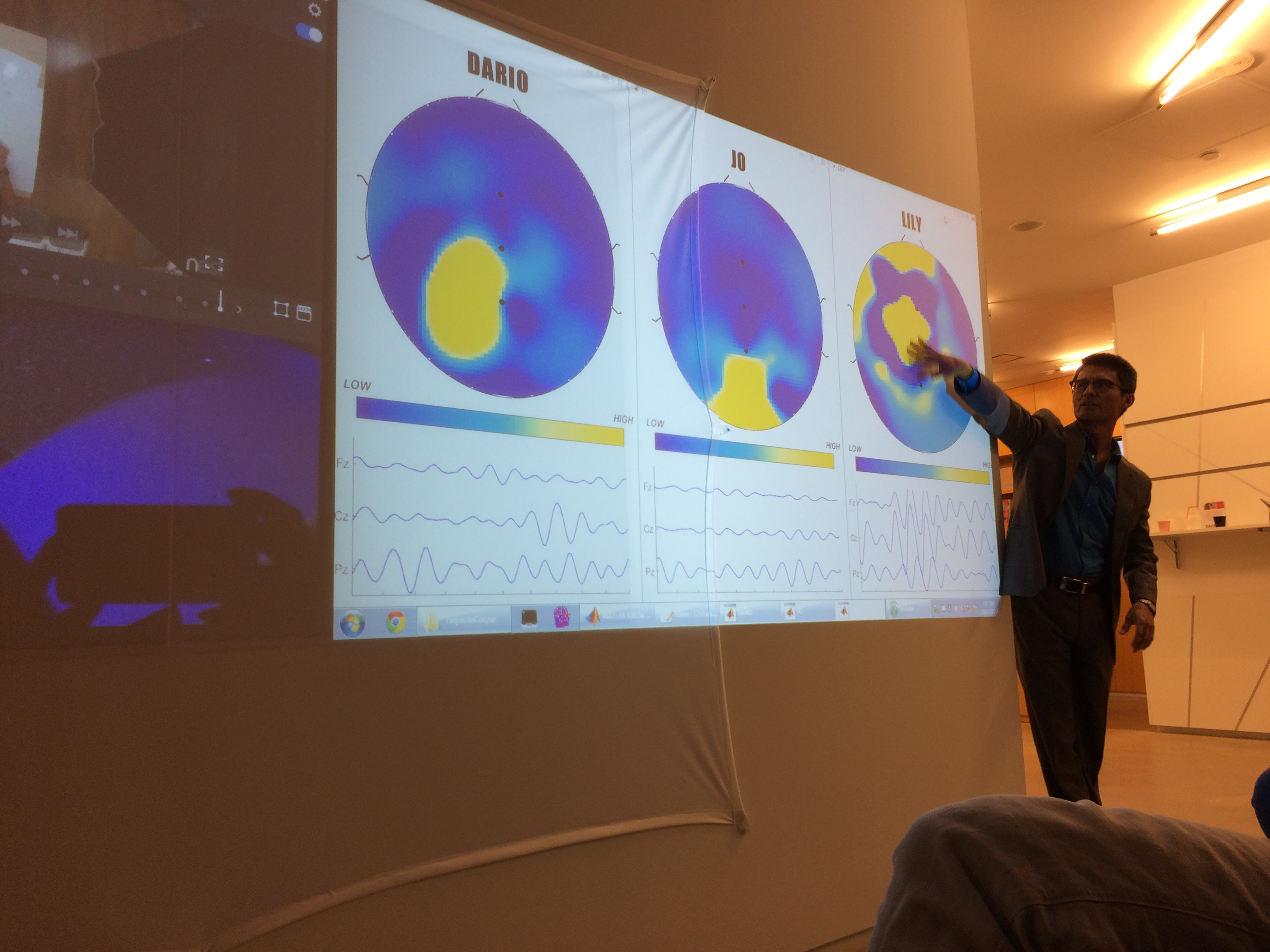

Last October, three local artists – Dario Robleto, JoAnn Fleischhauer, and Lily Cox-Richard – took part in an event that allowed people to watch what was going on in their brains as they created art. The process involved fitting each artist with EEG caps, which look like swim caps with 64 electrodes attached. As they worked on their pieces, a screen on the wall showed their brain activity in blots of blue and yellow.

To Cox-Richard, it’s a unique chance to help bridge the worlds of art and science.

“Being able to contribute and have it be a two-way street is part of what seemed like a really excellent opportunity for all of us to push this conversation forward,” she says.

It was just one of a series of similar experiments Contreras-Vidal has launched. The project is being made possible by funding from the National Science Foundation to advance science and health by studying the brain in action. Contreras-Vidal explains that, even though art is used as a form of therapy, there’s still a mystery surrounding what’s taking place up there to make it therapeutic.

While there have already been studies showing how creativity influences the brain, this one is different. What separates it from others is the fact that the brain is being monitored outside of the lab, such as while walking through a museum, creating art in a studio, or even dancing onstage.

“It’s as real as it gets,” Contreras-Vidal says. “We are not showing you pictures inside a scanner, which is a very different environment.”

Which brings me back to that art installation of the film projector at the Blaffer. While staring at it, I wonder, “What does my brain activity look like right now?”

I decided to find out. In the second part of this story, we’ll pick up with my EEG gallery stroll, followed by a visit to Contreras-Vidal’s laboratory to get the results.