Dell City is less than a square mile of one-story houses and storefronts, many shuttered. Acres of alfalfa fields surround the small town.

It may not look wealthy to some, but Dell City’s riches lie underground.

Wells fed by the Bone Spring-Victorio Peak Aquifer pump as much as 3,000 gallons a minute, providing Dell City with ample water for its 300-odd residents, its alfalfa farms and cattle ranches.

In the late 1990s, El Paso Water came to town, in search of land and the water that lies beneath it. Their plan was to pump water 90 miles across the desert to satiate El Paso’s growing population.

Residents of Dell City worried the water deal would spell the end to their livelihood carved out of the Texas high desert.

“The unknown was the factor,” Randy Barker, Hudspeth County Underground Water Conservation District’s manager, said. “People were saying, ‘El Paso is going to take our water away.'”

El Paso Water now owns over 70,000 acres in Dell City and holds permits to pump groundwater. While water importation has caused discord in the past, today this small town has reached something approaching a compromise with its much larger neighbor.

El Paso Water still doesn’t plan to import water until around 2050. For now, the utility leases nearly 50,000 acres of land to farmers, who continue Dell City’s agricultural tradition while introducing new techniques to prepare for a drier future. Dell City and El Paso residents all have a stake in conserving water, the most precious resource in West Texas.

The valley of hidden waters

The Mescalero, Lipan and Comanche people originally inhabited the Guadalupe Mountains and surrounding desert. The Mescaleros relied on harvesting native plants like agave and sotol and hunting game like mule deer and elk. But U.S. soldiers and cavalrymen forced out the Indigenous population by the late 1880s.

An oil prospector discovered the Bone Spring-Victorio Peak Aquifer in the 1940s. Dell City was formed when farmers began to irrigate with ample groundwater, fed by runoff from the Sacramento Mountains.

The early transplants had to figure out how to farm the sandy soil, churned by springtime dust storms. But soon fields of tomatoes, cotton and cantaloupe spread across the valley.

In 1948, the valley had less than 10,000 acres of irrigated land. That number rose to about 25,000 acres in the mid-1950s as new farmers arrived.

Jim and Mary Lynch came to Dell City from California in 1950. Their daughter, Laura Lynch, was born eight years later.

“Marketing went far and wide to try and get more people to come out to Dell City,” Laura remembered.

Dell City farms relied on Mexican labor through the Bracero program. But a series of setbacks kept Dell City small: in 1966 a devastating flood drove many of the smaller farms out of business. The 1980s farm crisis hit Dell City hard. And farming or ranching in the Chihuahuan Desert was never easy.

Jim Lynch put it in plain terms in a 2001 oral history interview: “We’re not making any money farming now and some of us wonder why we’re still doing it.”

‘We didn’t have rules in place to take care of the locals’

In the 1990s, El Paso Water CEO Ed Archuleta wanted to secure the city’s long-term water supply. The Hueco Bolson aquifer and the Rio Grande eventually would not be enough for the growing city. 1990s-era projections showed El Paso exhausting its water sources by 2030.

El Paso businessman Woody Hunt and Denver billionaire Philip Anschutz owned land in Dell City and encouraged El Paso Water to invest in the area.

“We didn’t have rules in place to take care of the locals,” said Barker, the water conservation district manager.

Under the Rule of Capture in Texas, property owners can pump as much groundwater as they choose, even if it impacts other landowners accessing the aquifer. Underground water conservation districts impose rules limiting groundwater pumping, overriding the Rule of Capture.

The Hudspeth County Water Management District adopted rules to validate the water use of landowners based off a specific historical period. Landowners who were not farming in that time period were shut out.

“That resulted in a lot of litigation,” explained El Paso Water CEO John Balliew.

Once the lawsuits were settled and landowners validated their water rights, El Paso Water began to purchase acreage.

“The rules came together and you had farmers who were willing to sell,” Balliew said. “We went in and started negotiating the purchases.”

The Lynches were among them.

“Ed Archuleta was kind and explained everything to everybody,” Laura Lynch remembered. “He spent a lot of time shaking hands and sitting down with people and just listening.”

The Lynch family entertained offers from other buyers in the United States and abroad. But El Paso Water convinced them. El Paso Water purchased the family’s 25,036-acre CL Ranch for about $50 million in 2016.

“From our standpoint, it was important that they were going to protect this community,” Lynch said. “It’s about the inevitable. We have more than enough out here, why not share with our neighbors?”

El Paso Water purchased 20 properties, totaling 70,000 acres, in the valley between 2016 and 2021, for a combined $222.38 million.

But Balliew and Archuleta were adamant: they didn’t want to destroy Dell City.

“What we are doing in Dell City is different, we’re not going to dry everything up,” Balliew said.

El Paso Water encourages conservation, attracts new farmers

The 1990s-era projections that El Paso would run out of water by 2030 won’t pan out, according to El Paso Water. The utility successfully encouraged water household conservation. They also developed new water sources, like the desalination plant. Growth slowed down and water-intensive industries left the city.

“We were able to do much more than we anticipated,” Balliew said. “There was no change in the planning, we were just pushing the need for import back.”

Now they expect to augment El Paso’s existing water sources with imported water around 2050.

El Paso Water bought time to develop their plans for Dell City and build trust in the community. Some farmers sold their land to El Paso Water and then leased it back to continue farming. On other properties, El Paso Water leased the land to new farmers.

“We’ve lost lots of old timers. They were tired,” said Barker, of the water district. “We have a good working relationship with El Paso Water.”

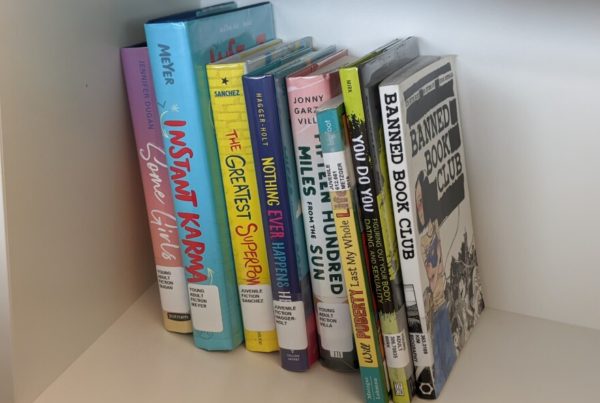

Jay Hill holds the largest lease and is in his fifth season running Dell Valley Ranch Management (DVRM) and Chaffhaye. Hill began farming where he grew up, in the Mesilla Valley in New Mexico. Chaffhaye sells premium, non-GMO alfalfa for forage.

“Dell City has a reputation for chewing up farmers and spitting them out,” Hill said as the springtime winds rumbled outside his office. “This is some of the hardest farming you’re going to find.”

Hill is reducing water use in the alfalfa fields.

“We are going to have to move to practices that are more sustainable,” he said. “It’s the only way we are going to survive.”

Flood irrigation is common in Dell City but uses large quantities of water. Farmers installed center pivots, massive irrigators that rotate around a field, which use less water.

Now, drip irrigation is the next frontier to conserving water. Through a grant from the Texas Water Development Board, Hill is piloting drip irrigation at the farm. The new technique could reduce water use by up to 30%.

Hill said climate change is a threat no farmer in West Texas can ignore. But he is convinced there is a way to keep farming responsibly.

“Right now (the water) I’m taking off that aquifer is at a level that is not going to be detrimental to the people that own the water or to the future generation,” he said.

Keith Newbill manages the Dell City properties and handles leases for the utility. He said El Paso Water sought out farmers who would be stewards of the land.

“The people who live on this land care for it more than anybody else in this world,” Newbill said. “There are very few people in agriculture who would willingly destroy their own environment.”

Farmers like Hill are starting to change attitudes.

“Now people are looking at it and going, wow, this might be a way to go down that road of sustainability that we so desperately need,” Newbill said.

Hill said building soil health is another challenge in Dell City, where high winds strip away the topsoil each spring. But using cover crops and reducing tilling he has steadily seen the soil improve.

He remembers the first time he dug up earthworms on the farm, a sign health soil was improving.

“We’ve got earthworms!” he remembered shouting. “We might make it now.”

Making a home in the valley

The face of farming in Dell City is changing, but many residents have stayed. Two restaurants, Rosita’s and Spanish Angels, serve breakfast and lunch daily. Business owners say the town empties out for the winter, but sales go up when farmworkers arrive in the summer.

The Reyes family bought the Two T’s Grocery in 2020.

“Here it is safe, safe, safe,” said Tencha Hortencia Romero, 79, in Spanish. “And we work, we toil, but we live well.”

Her granddaughters Julisa Reyes, 25, and Beneida Reyes, 20, often run the cash register. They keep cows, horses and a pony in the pens behind the shop.

Franceska Duran owns the Mercantile grocery store with her older sister, Patricia Duran, who also runs Spanish Angels Café and is the mayor pro-tem until the May elections. Franceska grew up in San Elizario and moved to Dell City from Dallas three years ago.

“If you’re working in Dallas, you’re just another face to people. But here people know you… …That’s really important,” she said.

Laura Lynch splits her time between Dell City and Fort Worth. She converts old buildings into AirBnBs, hosting visitors to the Guadalupe Mountains, stargazers and people visiting family and friends in town. She appreciates the ideas younger farmers are bringing to the valley.

“The millennials came out here and they brought absolutely fresh eyes to the valley,” she said. “They saw things that I take for granted all the time.”

The future of Dell City looks bright to residents

Water importation is full of cautionary tales. California’s Owens Valley nearly dried out to feed Los Angeles. Arizona banned the practice with a few narrow exceptions. Landowners in Lee County, Texas, say San Antonio’s Vista Ridge pipeline is lowering their well levels.

Water transport from Dell City to El Paso is still decades away. There are many unknowns: the exact amount of water pumped from which property, how much land the utility will continue to lease to farmers, if any, once importation begins.

El Paso Water estimates its peak water import levels will only be a quarter of what agricultural irrigation in Dell City consumes today.

But for now, El Paso Water has won over many residents with its commitment to water conservation and helping agriculture in the Valley of Hidden Waters continue.

New farmers to the valley like Jay Hill see a future in Dell City. He put his children in the school, leads the Future Farmers of America chapter and volunteers on the town ambulance.

And old-timers like Laura Lynch said the land sales didn’t spell the end of Dell City.

“There was the fear of this big, bad city coming into the little, poor people in town and taking advantage,” Lynch said. “Well, not really, we’re still here.”

Danielle Prokop of El Paso Matters contributed to the reporting and writing of this article.

Staff writer Martha Pskowski may be reached at mpskowski@elpasotimes.com and @psskow on Twitter.

This article first appeared on El Paso Matters and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()