This is the third story in a three-part series about HemisFair ’68. For part one, click here. For part two, click here.

Today, if you stand at the site where San Antonio held a World’s Fair 50 years ago, you’ll see structures that define San Antonio, like the Tower of the Americas, for one. What you won’t see, though, are too many remnants of what used to be there – what was cleared away for the fair to take place.

Just south of downtown San Antonio, artist Anne Wallace is showing me a map of streets that no longer exist. They have names like La Fitte Street, where Sudden Cleaners used to be. And Sycamore Street where the Deluxe Hotel and O’Krent Venetian Blind Company once stood.

“Everyone who lived here,” Wallace says, “they worked, they socialized, they had dinner they shopped, so it was like a small town.”

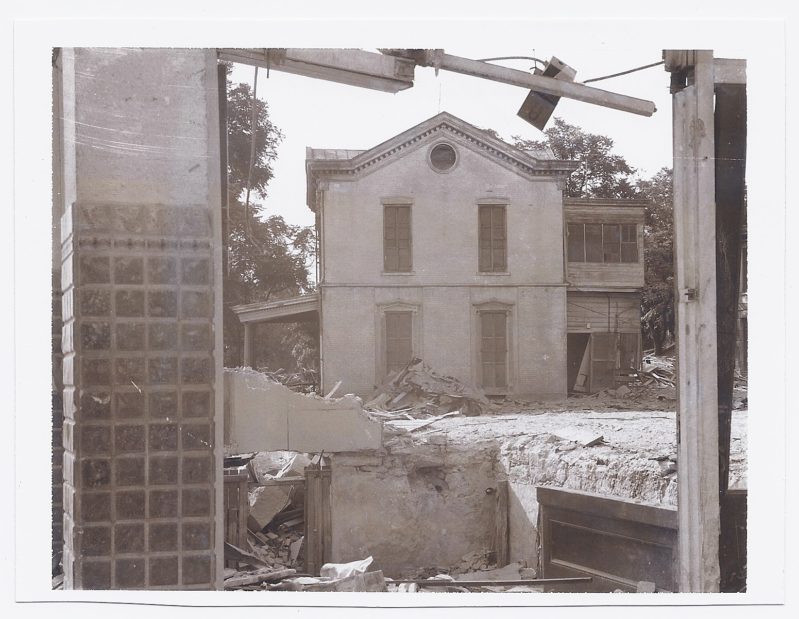

Wallace lives near the area, which she’s researched for public art projects. The neighborhood was seized and then demolished to make way for the 1968 World’s Fair. Over 1,300 buildings were torn down. Over 1,600 people were displaced.

“The theme of HemisFair was confluence of civilizations,” Wallace says, “which I find so ironic because actually these downtown neighborhoods really were the confluence of authentic cultural expressions of south Texas.”

It was an old neighborhood, tight-knit and working class, populated by Latinos, Germans, African-Americans, Czechs and others. It sat in the heart of the city on the southeast edge of downtown, next to the San Antonio River. Vincent Michael is the executive director of the San Antonio Conservation Society.

“Because it was such a choice location near downtown, and because it was deteriorated – you could definitely see the ravages of time – it was an obvious choice,” Michael says. “90 acres right there next to the downtown Riverwalk.”

The goal of HemisFair was to expand San Antonio’s tourism industry. It would do that by building things like a convention center, arena, performing arts center, and the Riverwalk – all of which city leaders wanted to put downtown. But they didn’t have a lot of money to spend. So organizers looked at areas that could qualify for a program called urban renewal that at the time was seen as a way to modernize cities. It worked like this: the federal government gave cities money to seize a rundown area, tear everything down, and then build something new. In the 1950s and 1960s, urban renewal happened in downtowns all over the United States.

“By the end of it you had millions of people that were moved,” Michael says.

One condition for urban renewal was that it had to affect a slum or blighted area, but people familiar with the HemisFair neighborhood say it wasn’t really like that. James Eng and his mother came to San Antonio from southeast China in 1931. His father was already there, and had started a grocery business with his brother and Eng’s grandfather. The store and the Eng house were both in the HemisFair neighborhood.

“They, of course, tried to upkeep it, improve on it,” Eng says. “They lived in it. So because of that, the neighborhood was not really rundown looking. No, it was kind of well-kept in a way.”

The grocery business prospered, and Eng’s father eventually wanted to save enough money to move back to China and retire. But after the store was demolished, he never owned another one. He worked in other people’s stores, and Eng’s parents remained in San Antonio until they died.

“They were not ever really happy since the HemisFair situation came up,” Eng says.

Not all of the structures would be demolished. The plan was to use some of them for the fair, and about two dozen were saved. Mike Garcia’s job was to sketch and measure the neighborhood’s buildings and suggest which ones to keep. He spent day after day in the neighborhood drawing houses and stores and churches. And while he was there he’d meet some of the residents.

“Like this particular German-American lady, very elderly,” Garcia says. “I was talking to her and she said ‘This is going to be wonderful. I’m going to be all around the fair.’ And I said ‘No, I think you’re going to move because the house will be taken down.’ And she said ‘Oh no, this house is very old.’”

She didn’t realize what might happen to her home, and she didn’t have any family around to help her out. So Garcia went to St. Joseph’s Catholic Church, where the woman was a member, and explained the situation to the monsignor. The monsignor said he’d go talk to her.

“And he did,” Garcia says. “And then several months later as the fair started, I went back and visited with the monsignor. And he said yes, she moved out. The sad thing is we placed her in a beautiful retirement home, where she had the best of the best. But she passed away. She had no friends, she didn’t recognize anything, so she just died. Of a broken heart, he said.”

Although some of the residents were heartbroken or angry about having to move, not all of them were. Some were even happy since they were compensated for their property. But Bexar County Judge Nelson Wolff says it’s not something the government would be able to get away with today.

“They’d hang you today,” he says.

Now, local leaders like Wolff are forming the future of the HemisFair property. There wasn’t a plan for what to do with it after the fair closed in October of ‘68. So besides expanding the convention center, not much has happened on the site for the better part of 50 years. But that’s changing. Now the city has a plan that will transform the site once again. The redevelopment is already underway, and the idea is to bring in shops and restaurants, workspaces and museums, and, yes, housing.