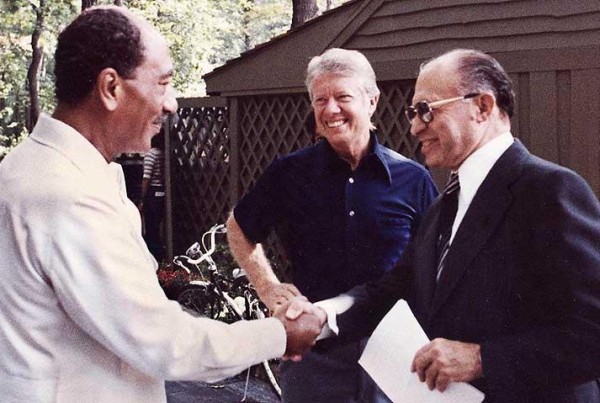

Half a century ago, Pres. Lyndon Johnson teamed up with the ad men of New York to produce one of the most famous – and controversial – political ads of all time.

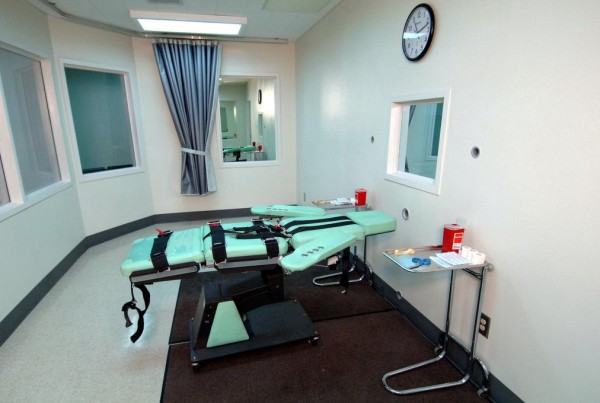

A young girl lackadaisically plucks the petals off a flower, counting as she goes. But soon, her count is interrupted by a mission-control style countdown: when it ends, a mushroom cloud envelops the screen. “These are the stakes,” Johnson intones. “To make a world in which all of God’s children can live, or to go into the dark. We must either love each other, or we must die.”

Produced for Johnson’s 1964 campaign, “Daisy” only aired once as an ad – although it was rebroadcast and analyzed by the pundits of the day. Still, it forever changed the landscape of American politics. And now, on its 50th anniversary, its influence is as strong as ever.

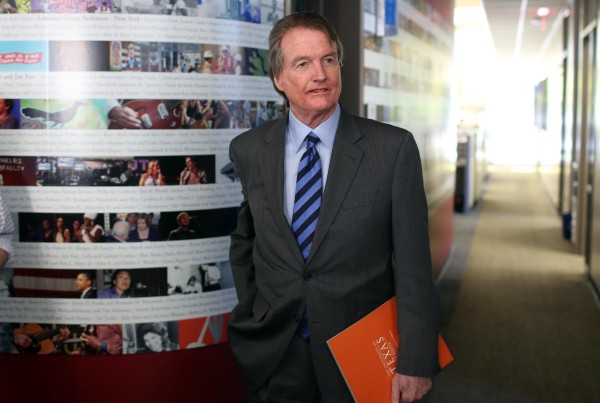

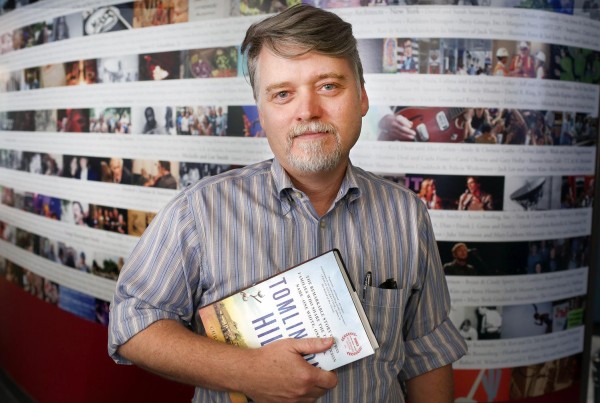

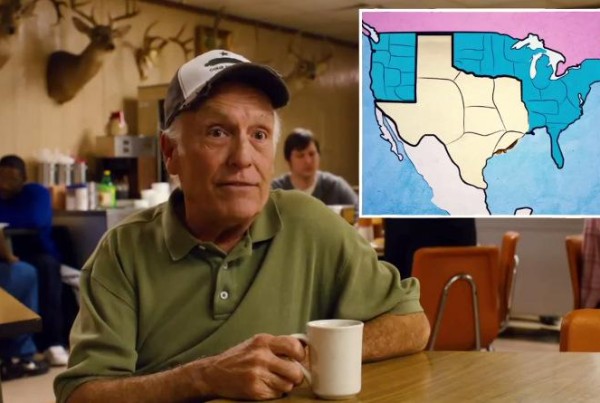

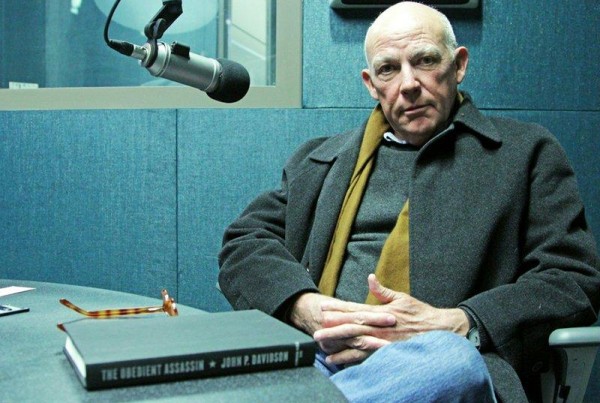

Robert Mann, a professor of mass communications at Louisiana State University, recently penned a piece for Politico about the ad. He spoke with Texas Standard’s David Brown about Johnson’s groundbreaking commercial and its lasting legacy in political advertising.

Interview highlights

On the scope of the ad:

“I estimate about a hundred million people saw it that week [broadcast originally, and then on the news] … That’s a huge audience for 1964 – that’s about 60, 70, 80 percent of the electorate watched that spot depending on what your estimate is of the number of people who saw it at least once.”

On how the ad was different:

“What one of the brilliant aspects of the daisy girl spot was they never mentioned [Republican presidential nominee Barry Goldwater], never showed his image, because they didn’t need to. The audience already had a lot of information on Goldwater’s reckless positions and statements on nuclear war and nuclear weapons … they were trying to use what the voters already knew.”

On why this kind of political advertising stuck:

“This showed that spot advertising could be really effective, not just in selling soap and soup, but also candidates and so the political candidates in the next presidential election and other elections around the country thereafter realized ‘Okay, this is the way we reach voters and this is how we do it.’”