From Texas Public Radio:

When Marsha Madrigal was in middle school, she thought it was normal to see her classmates in handcuffs.

But she knows now that not all schools have a significant police presence, and the odds of seeing your classmates arrested go up if you are Black, like she is.

The 2018 Fox Tech High School graduate wants the San Antonio Independent School District to remove police from its schools so future middle schoolers never think it’s normal to see classmates in handcuffs.

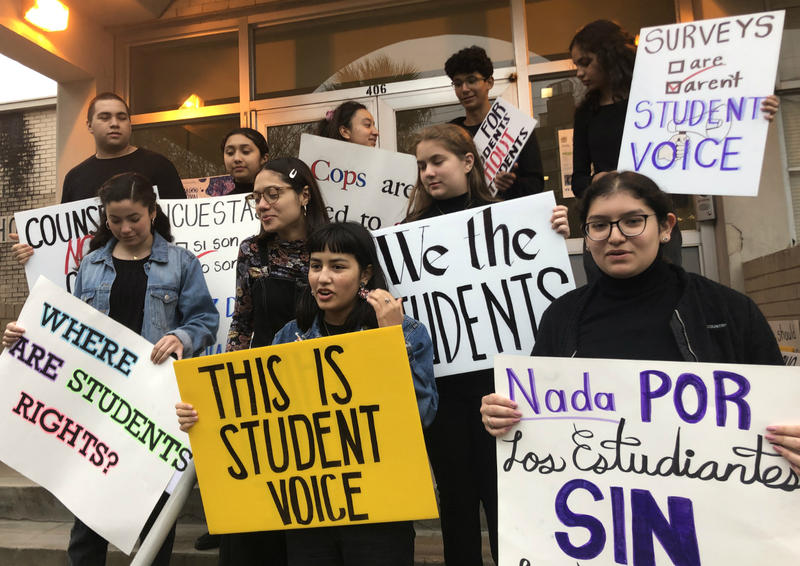

On June 22, the night that San Antonio ISD trustees were scheduled to approve the budget for the 2020-2021 school year, the board was inundated with calls to get rid of the district’s police department, many from current and former students.

SAISD Chief of Staff Tiffany Grant read emailed comments for nearly two hours during the live-streamed meeting, cutting each comment off after one minute to save time and enable more comments to be read.

The calls echoed letters advocacy groups sent to urban districts across Texas, including Dallas, Houston, San Antonio and Austin.

Advocates point out that researchers haven’t been able to find evidence that police make schools safer, and Black students are more likely to be arrested than students of any other race or ethnicity.

Students of color, students with disabilities and LGBTQ+ students are also overrepresented in school discipline and arrests nationwide. They are more directly impacted by police in schools than any other group involved in the growing debate about school-based officers.

So far, none of the Texas districts have heeded those calls. But after the death of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer, school systems in several U.S. cities, including Minneapolis, have voted to remove police from their schools. Other school systems, including the Los Angeles Unified School District, have voted to reduce funding for school police.

Many of the comments submitted to SAISD were from current and former SAISD students. They’re part of a generation of young people that’s becoming known for their activism before they’re even old enough to vote.

Although the district approved a student handbook that emphasizes alternative discipline practices in 2019, student advocates told TPR that little has changed. They say police regularly interrupt class to check for drugs, and escalate minor fights by slamming students to the ground and putting them in handcuffs.

Here’s why five student advocates say it’s time for their district to stop spending money on school police.

Marsha Madrigal, Fox Tech High School Class Of 2018

When Marsha Madrigal was in 8th grade, she was given two weeks of in-school suspension after her Spanish teacher noticed that the tips of her hair were dyed dark purple.

Marsha Madrigal graduated from Fox Technical High School in San Antonio as the 2018 salutatorian.

“I wasn’t allowed to be in their classroom because my hair wasn’t the standard,” said Madrigal, whose father is Black and mother is Mexican American. “But you had either a fair-skinned Latina woman or a white girl who attended the same middle school as me and had her whole hair dyed bright pink, and she was never subjected to the same harsh disciplinary measures as I was.”

During her two weeks of in-school suspension at Longfellow Middle School, she was joined by two other Black girls. Madrigal said there were only four Black girls in her entire school.

“There are only four of us, but 75% of us are in suspension, where we’re not allowed to collect the work that we need to stay on track (but are instead given busy work).”

Madrigal said those two weeks in in-school suspension showed her how easy it would have been to get caught in a cycle of punishments — until she landed in the criminal justice system or dropped out of school.

She was unable to attend class for two weeks, and was given simple busy work instead of assignments from her teachers, putting her behind in class. She was tempted to stay home, since she wasn’t learning anything. But if she did, she would have been punished with more time in in-school suspension. Meanwhile, no one asked her why she was upset about her punishment, or checked in with her to see if anything was going on at home.

“And guess what, the home environment is one of the reasons why I might have reacted maybe not the best way in the first place that might have got me into (in-school suspension). But that was never addressed, and so the cycle continues,” Madrigal said. “I’ve witnessed very bright, very smart people get arrested at school, get pushed out, go to Estrada (Alternative Center) and then just never come back.”

According to Paula Johnson with the Intercultural Development Research Association, Black girls often bear the brunt of vague discipline infractions like showing disrespect or having an attitude.

“The policies that are in place are so ambiguous and broad that it allows for something as simple as a heavy sigh being taken as what would be called intentional disrespect of an adult. And that student can be suspended for that,” said Johnson.

As director of IDRA’s Equity Assistance Center, Johnson conducts equity audits of school districts in 11 southern states, including Texas.

Her organization is one of the advocacy groups behind the letter sent to SAISD asking the district to divest from school policing.

“Black students do not actually misbehave on a higher level than their peers, but they are usually referred to either the office or the school police for the same reasons that another student maybe gets a warning. And so that’s where that bias comes in that is criminalizing the behavior of Black students,” Johnson said.

As one of a handful of Black students at Longfellow and Fox Tech High School, Madrigal said she felt like she couldn’t fully be herself without facing consequences.

“I can’t feel the way I want to feel, I can’t express my emotions the way I want to express my emotions, because I feel like if I mess up, it’s going to reflect really poorly on me,” Madrigal said.

She believes that police presence in schools makes situations worse, not better, and that the district’s money is better spent on social workers and mental health experts that can help students experiencing hardship and trauma.

“The district knows that we’re going through all this stuff,” Madrigal said. “They want to give us police? Why not give us the people we need to work through our emotions? Why not hire some board-certified therapists that specialize in domestic violence, that specialize in immigration?”

Current SAISD student advocates say not much has changed since Madrigal graduated, despite the adoption of a new discipline policy and student handbook at the beginning of the 2019-2020 school year.

At the urging of the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition and other advocacy groups, trustees revised the policy to explicitly state that police should not be involved in routine discipline. The policy also encourages administrators to adopt restorative practices that address the root causes of behavior in order to reduce suspensions.

But student advocates still enrolled at SAISD say they haven’t noticed much of a difference.

Alejo Peña Soto And Nickoll Garcia, Both Rising Seniors At Jefferson High School

“I’ve seen instances where police have enforced sort of punishment for just really miniscule things, like having your hood on in the hallway or sagging your pants, things that they shouldn’t be getting involved with, but they still do,” said Alejo Peña Soto, a rising senior at Jefferson High School. “It’s not as present as it was over the past two or three years, but it still happens.”

Peña Soto said he hasn’t seen a push for change at his school. He believes his school leaders are more comfortable with involving police because several administrators have a military background.

One of Peña Soto’s classmates at Jefferson High School is Nickoll Garcia. She said officers routinely interrupt class to search for drugs.

“You never know (when or why). They will just knock on the door, and then all the students have to leave (the room),” Garcia said. “And then they usually will have a dog there with them to kind of sniff around to see if there’s any drugs. Usually they never find any sort of drugs, so it’s just interrupting the class. And then you go back in, (the officer says) ‘Thank you for your cooperation,’ and then they leave. And then you just never know when it’ll happen again.

“I feel like that really kind of shows how they place more of an importance on criminalizing students than educating them,” she added.

Ariel Alvarez, Burbank High School Class Of 2018

Ariel Alvarez, who graduated from Burbank High School in 2018, said drug searches were common practice at her school too, and according to her younger sister, who is a rising senior at Burbank, not much has changed since she graduated.

“Usually when people do a search, they have to have a warrant, but when it’s in a classroom, they don’t have to have anything,” Alvarez said. “They get to just storm in there and just see what’s in kids’ backpacks and take their snacks or their drinks.”

Burbank teacher Luke Amphlett said he finds the use of dogs especially troubling, because of the history of white Americans using dogs to perpetuate racial violence as far back as slave catchers.

“I’ve seen a lot of students pulled out of a lot of classrooms and made to stand in the hallway, treated as suspects in crimes that there’s no evidence have even happened,” said Amphlett, a member of the teacher union social justice caucus who has helped the students advocate for themselves.

Alvarez and other students said police are also called whenever conflicts arise among other students or with teachers. They feel like the officers escalate situations and put students at risk.

“It made me feel really scared for the students, because there’s grown men who are like built — built like grown men — just throwing kids around and off of each other,” Alvarez said.

“It’s really scary, because they have the weapons on them on campus, so you don’t know what’s gonna happen. I lived in a time after Trayvon Martin, I lived in a time after so many other instances of police brutality, and I just didn’t want things to escalate.”

Alvarez said she saw three or four fights during her four years at Burbank, and even those conflicts could have been resolved by bringing in a counselor instead of a police officer.

“Nobody ever brought weapons. It was just fists and things like that. And usually it was over girls,” Alvarez said.

She worries that arrests may have had outsized consequences for her classmates.

“Someone has to get that kid out. And God forbid, his parents are undocumented, or God forbid, he isn’t documented,” Alvarez said. “That just creates a whole ripple effect of problems for these students.”

She remembers seeing a classmate who didn’t speak English get arrested, and then not seeing him again for at least a year.

Adelyn Hernandez, Rising Freshman At Fox Tech High School

13-year-old Adelyn Hernandez said she saw police break up a fight while she was still in elementary school at SAISD’s Booker T. Washington Elementary, and then again when she was at Judson ISD’s Metzger Middle School.

“I have seen (my friends) getting put in handcuffs, being thrown up against the wall. Like, just for a fight because the administration gets tired of it,” Adelyn said. “The admin will directly call the police. They won’t even ask questions or deal with the situation.

“As soon as (the officers) get there, (my friends were) detained like criminals, even though we were in middle school,” Adelyn said. “They still treated them like adults, putting all their force on to them — like all that strength that they have, even though these are adults, and we’re children still.”

Research shows that adults see children of color, especially Black boys, as older than they actually are.

Johnson, with IDRA, believes school administrators should handle fights themselves instead of calling a police officer. State law does not require districts to report fights to law enforcement unless there is a weapon or there is a serious injury.

“If a student resource officer or a police officer were to get involved and cite them, that is now on a record,” Johnson said. “They’re missing school, they’re missing instruction, their grades may go down…That’s how we end up with students dropping out of school.”

She believes that the problem with police in schools is that part of their job becomes policing students instead of protecting them from outside dangers.

She’s offered to conduct an equity audit for SAISD, and said IDRA’s federal funding would most likely cover the cost.

Personal Experiences

As a member of the SAISD Student Coalition, Peña Soto has been advocating for changes to the district’s discipline policies for months.

“Some of the first meetings we had, we’d spend half the meeting talking about how there isn’t enough mental health support at schools, and how we felt district wide there wasn’t enough support for students,” Peña Soto said. “But then there was also this overfunding of police when it wasn’t necessary at all. It was a way to control students and control them in a way that wasn’t appropriate at all.”

Wagner High School teacher Trevor Taylor hugs a former student at a Black Lives Matter protest in June. Both students and teachers have been active in local protests.

But after the death of George Floyd inspired Black Lives Matter protests across the country, sparking conversations about the role of police in schools, Peña Soto said the student coalition decided it was time to push for an end to school police entirely.

“I understand that schools in this country historically have — that we’ve (had police in schools) for a long time. But that doesn’t mean it’s okay. And I think that now, more than ever, is the perfect time to push away from systems like that,” Peña Soto said. “I think the district is quick to dismiss what we propose because we’re students sometimes. They feel like we don’t understand what’s going on, but we do. We have the ability to research, we understand what’s going on, and we’ve seen the research that suggests that policing is not necessary.

“One of my first days at Jeff, a boy was put in handcuffs because he ordered a pizza. Which, you know, when you see stuff like that, it’s hard to see the benefits of having them on our campus.”

As a student, Peña Soto, who is Latino, said he’s never felt threatened by a police officer.

“But that’s not the point, right? I’m lucky enough to have good grades and to kind of be seen as a student who’s not a troublemaker. I think that there’s a big difference when I look at some of my friends who may be labeled as being different from me and more likely to, I guess, cause issues,” he said.

“I think that there’s definitely sort of a double standard when it comes to students. And I think there is some form of, even if it’s unintentional, bias when it comes to policing students, right, that doesn’t just stop at policing. It happens with administration as well.”

Peña Soto said he and a friend were racially profiled by a police officer one day while they were walking to the library after school. The officer assumed they were skipping school and wanted to take them back to verify their story.

“I am a person of color. I was with my friend who’s African American. It just felt like this was an obvious case of profiling and when stuff like that occurs… it’s just extremely frustrating as a student to see our district support the police,” he said.

“It makes you just feel like you are lesser and that the people around you consider you as lesser when they treat us like that.”

Adelyn Hernandez thinks police don’t need to be at schools unless someone has been hurt or there is a lockdown for a possible school shooting.

Her experience with police outside of school makes her uncomfortable with the idea of being around them all day at school. She’s seen her parents and uncles be pulled over for no apparent reason.

“I can say with full honesty that not all police are bad, but the experiences that I’ve had with police, most of them, they’re not good. And I feel like the justice system is messed up and they treat us differently because of the color of our skin, or what side of town we’re from, how much money you have,” said Adelyn, who lives on San Antonio’s East Side.

A few years ago, her mom was arrested after questioning the purpose of her being pulled over.

“She felt like she wasn’t treated equally,” Adelyn said. “They took that the wrong way and they ended up taking her into custody.”

Even though she hasn’t interacted with police at school so far, she’s seen her friends put into handcuffs at Washington Elementary and at Judson ISD’s Metzger Middle School.

Students of color are more likely to be arrested and disciplined at schools across the country. Advocates would like to see an end to school policing in all Bexar County schools.

“I feel that all the money that they waste on officers, they can use it on classes, teachers, new teachers, better food, because at school sometimes kids don’t even eat at home,” Adelyn said. “If we’re not going to be treated good, they’re not going to feel like they want to go to school.”

Hallie Gilliland doesn’t believe SAISD needs to remove all police from schools, but she does believe officers need to have the right training and temperament to be around kids.

Last year at Sam Houston High School’s new P-Tech center, one of Hallie’s classmates came to school while he was suspended. Their teacher called the police, and he ended up tackled to the ground and handcuffed.

“It was very uncalled for,” Gilliland said. “They should have brought the boy to the peace room and let him calm down …and let them call his mom and (have her) come get him, because it did not have to be taken out of proportion like that.

“He came to the classroom and went to sit down in class, and the teacher was getting aggressive with him so he tried to go outside the room,” Gilliland said. “He tried to go around her, and she thought he pushed her. And she called the cops.”

What Happens Next?

On June 22, the SAISD board approved next year’s budget without changing the $6.8 million allotted for district security, including the district police department.

During the meeting, trustees expressed support for the district’s police chief but left the door open to further discussion about budget priorities by noting that the budget could be amended later.

However, in an interview later, Board President Patti Radle confirmed that the district is not considering getting rid of its police department.

Radle also said she doesn’t want to redirect part of the police budget to mental health resources or ethnic studies courses, as advocates asked.

“We have a police department who is short on their budget already for certain things,” Radle said. “It’s not a matter of taking money out of the police department, it’s a matter of continuing to seek for more funds, because we need a whole lot more strength in the counseling and in the social work and in mental health.”

Alicia Perry, the district’s only Black trustee, said during the meeting she would like to ensure that the budget for counselors and social workers equaled the police budget. Radle said more money is spent on mental health than it appears from the budget, because of funding from outside partners like Communities in Schools.

While students and other advocates would like to see a complete divestment from police, they said they’d be happy if, in the meantime, the district fully implemented the changes necessary to live up to the promise of the handbook it adopted last year.

“We want to see something that’s real and legitimate, and we want the district to be transparent when it’s making these decisions,” Peña Soto said.

For instance, 16-year-old Hallie Gilliland enjoyed being able to go to a peace room at Sam Houston High School’s P-Tech campus last year. Spaces like peace rooms that give students a place to decompress and regroup when they’re upset are a common part of the restorative practices recommended in the student handbook. But Hallie said the room closed down part way through the year, and students aren’t sure why.

“It was very upsetting, because that was the only way I could really have somewhere to open up and somewhere to just relieve stress and just kind of get away from my problems,” said Hallie.

Burbank teacher Luke Amphlett said an initiative for students at-risk of dropping out run by the Martinez Street Women’s Center incorporates restorative practices. Overall, however, he said his school has become more punitive over the last few years, not less.

“For the overwhelming majority of our students, that is the reality. And when we talk about supporting restorative practices, what we have to talk about is restorative practices everywhere for every student. And anytime that we’re not doing that we’re failing,” Amphlett said.

Radle acknowledged that campuses still involve police in discipline sometimes, and that the switch to restorative practices instead of punitive discipline was a work in progress.

“There’s still a lot of work to be done, but as you begin to do this work, there is a lot of planning and there is a lot of training. There’s a lot of having to change (teachers’ and officers’ minds). It’s a lot of work building culture,” Radle said. “No matter what rules you have in place, there are people that are going to break them, there are going to be people that ignore them.”

“We know we have a lot of work to do. We just want people to notice that we’ve been working on it. You know, we’re not starting from zero here,” she added.

Especially after school shootings in Parkland and Santa Fe, both advocates and trustees noted that there are a lot of people who want police in San Antonio schools. But because research hasn’t shown that school-based officers keep schools safer, and has shown negative effects for marginalized students, including lower graduation rates, advocates believe they shouldn’t be in schools.

“I’m a huge believer in democracy, but I also think we have to make sure that we push back on the idea that things that are wrong are acceptable if lots of people think them,” Amphlett said, pointing out that a large portion of the American population opposed desegregating schools during the 1950s and 60s.

“People’s thinking shifts and people’s thinking shifts by having serious conversations about things. And there’s never been a serious conversation about this.”