From Marfa Public Radio:

In late March, the Mexican government began routing transmigrantes – Central Americans who make a living towing used cars and secondhand goods across the United States to the Mexican border and on to their home countries – through Presidio.

For some in the rural border town, there’s hope transmigrantes could usher in a new wave of business to an otherwise money-strapped city. But, for others there are concerns that this influx of traffic may cause more headaches than its worth.

Outside the Presidio-Ojinaga port of entry, a slow trickle of cars and trucks moves through the two cities, passing between the U.S. and Mexico.

The kind of cross-border traffic this corner of the state typically sees is commercial and pedestrian — usually people looking to visit family, shop and eat. But now, the rural border town is home to a new kind of traffic headed for Ojinaga: transmigrantes, Central Americans who make a living towing rusty cars and secondhand goods from the U.S. across the Mexican border to their home countries, hoping to resell their wares for a profit.

“They’ll be coming straight down this road,” said Presidio Mayor John Ferguson, gesturing towards U.S. 67, the only highway running through his city.

For nearly two decades, the South Texas city of Los Indios has been the only border crossing where transmigrantes were allowed into Mexico to continue their journey south. But in late March the Mexican government designated Presidio as a second crossing point.

“They’re businessmen, they’re working hard like anybody else,” said Ferguson. “They’re permitted by the Mexican government to travel through Mexico from north to south, reaching the Mexico-Guatemala border .”

Ferguson said Presidio was picked as an additional port for transmigrantes because Mexican officials felt the port in Los Indios was being inundated with traffic. Mexican leaders were also worried about extortion transmigrantes faced from cartels after crossing into Mexico from Los Indios, according to a 2018 briefing to Mexico’s President arguing for this new route.

Since March 23, Presidio has been open to transmigrantes and the loads they carry — household items and junk cars, usually purchased at auction houses across the U.S.

“Once they purchase all these things, they normally will have like a mid-sized Toyota pickup or something, and [are] towing a second vehicle,” said Ferugson. “That’s how you can always spot them.”

Before the pandemic in 2019, at an oil-stained parking lot in Marfa, transmigrante Bener Lopez was looking over the items he was hauling back to Guatemala: a motorbike, washing machine and worn bathroom scale.

“Here we have things we sell over there” in Guatemala, Lopez said in Spanish. “Everything is second-hand.”

Along with the 1985 Toyota he was hauling, there were a few thousand dollars worth of goods in the bed of the truck. He said he’s done this kind of work for a few years, and thanks god for the opportunity to provide for his family.

The truck transmigrante Bener Lopez was hauling was filled with worn goods, like a ladder, a bathroom scale, and even a motorbike. He took these items back to his home country of Guatemala to sell there.

Carlos Morales / Marfa Public Radio

Transmigrantes like Lopez bring their goods through Mexico, traveling along roads the Mexican government has designated for transmigrante travel to other countries like Guatemala. Some transmigrantes are dual citizens of Guatemala and the U.S.

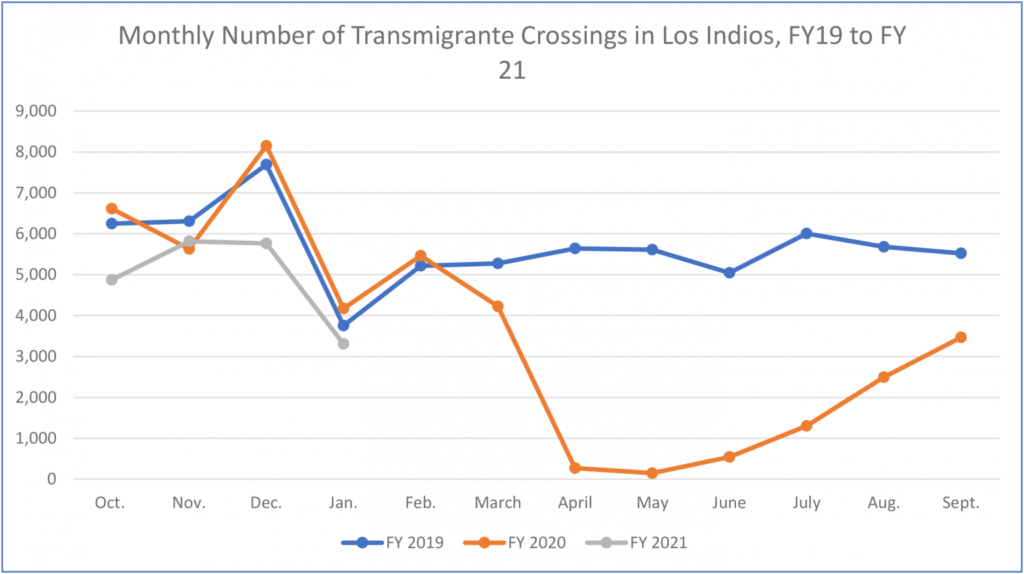

At one point, there were multiple ports of entry for transmigrantes along the Southwest border for transmigrantes to cross, including El Paso. But beginning in the early 2000s, transmigrantes were allowed only at Los Indios, where such crossings generally reach a few thousand per month.

During the pandemic, those numbers dropped but are now on the rebound, says Jared Hockema, the Los Indios City Administrator.

“There are times that there’s a lot, there are times where there’s very few,” Hockema said in a phone interview. “But they’re all crossing, throughout the year.”

Right now, transmigrantes need to wait in the U.S. up to 72 hours — sometimes longer — while their paperwork to cross is processed. Hockema says during peak seasons, usually in December, the line to cross into Mexico stretches for miles.

“They’ll line up on the highways, they’re in town,” said Hockema. “And so it can become a dangerous situation with people moving in and out of traffic, pedestrians, people parked on the shoulder.”

Source: Cameron County

When Presidio Mayor Ferguson sees the number of transmigrantes that have passed through Los Indios in the past, he thinks about the potential traffic Presidio, a city of about 5,000, could see.

Currently the city’s one port of entry is under construction and will soon expand to four crossing lanes. But the decision to expand to meet Presidio’s and Ojinaga’s needs was made before transmigrantes were allowed to come through the region. That worries Ferguson, who’s also concerned about how transmigrante traffic could impact daily life, and the city’s only major highway, U.S. 6.7.

“It’s a two lane, hilly road, and not many opportunities, not many passing lanes and, you know, just lots of places where people could get in trouble if they don’t drive prudently,” said Ferguson.

But others in Presidio, a city with few industries, see transmigrantes as a potential boon to the local economy.

“There’s going to be a wide range of opportunities for not only the brokers, but for other people,” said Presidio’s Isela Nuñez, an import-export broker, who already works with cross-border goods, like machinery, cattle and vegetables.

She says her business is prepared to fill out the required paperwork for transmigrantes and the loads they carry, but is holding off on hiring any new employees because it’s too early to know what the demand will be like.

“We’re creatures of habit,” said Nuñez, theorizing transmigrantes will likely continue traveling through Los Indios, at least for now, because it’s what they’re familiar with.

“These [transmigrantes] already know how it works, where to go, where to stay, what to do in Los Indios,” said Nuñez. “I think at the beginning, it’s going to be slow.”

A few businesses in Presidio are preparing for transmigrantes to come through their city. One business built a paid parking lot and another is bringing in mobile homes where transmigrantes can stay the night.

Carlos Morales / Marfa Public Radio

There are local businesses in Presidio ramping up ahead of what they hope will be steady traffic. A sign off the highway reads “bienvenidos hermanos transmigrantes,” where one business has set up a paid parking lot near to accommodate transmigrante trucks. Another is bringing in mobile homes where transmigrantes can stay the night.

But Mayor Ferguson isn’t sure what transmigrantes might mean for the local economy.

“The transmigrante traffic will contribute somewhat to our local tax base through fuel sales, food sales, things of that nature,” said Ferguson. “But we’re not putting out our hopes that it’s going to be a goldmine for us.”