From the Texas Tribune:

This story is published in partnership with Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for the ICN newsletter here.

VAN HORN — When word spread this summer among residents of this small West Texas town that a 48-inch diameter natural gas pipeline — larger than others in the region — was coming their way, they saw it as a threat to their town’s tranquility and sense of security.

Van Horn resident Yolanda Carmona learned that the proposed Saguaro Connector Pipeline would run underground near a property she recently bought at the edge of town. The third-generation cattle rancher has deep family roots in Van Horn, a town that straddles Interstate 10 and sits midway between El Paso and Midland-Odessa.

Even though Carmona works for the city as an events and tourism director, she said she first heard of the pipeline this summer when the Property Rights and Pipeline Center, a national nonprofit, held an informational meeting in town.

“I really had no idea what was coming, not a single clue,” she said.

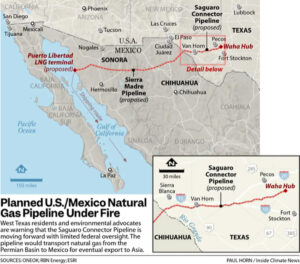

The proposed Saguaro Connector Pipeline would transport natural gas from the Permian Basin to the U.S.-Mexico border, passing within one mile of Van Horn, where 80% of the population is Hispanic and the median household income is just over $37,000 — about half the state median.

Saguaro would connect to another proposed pipeline in Mexico to transport gas to the coast of Sonora, where a proposed facility would liquify it for export to Asia and South America in tanker ships. The liquified natural gas (or LNG) export project in Sonora, called Saguaro Energía, has been in the works since 2018.

Suddenly the future of this 2,000-person town was tangled up with the global natural gas market. Van Horn residents in the pipeline’s path worry their small town doesn’t have the emergency management capacity to respond to explosions or leaks along the pipeline, and they are distraught that local land would be snatched through eminent domain for construction. They question why they should sacrifice their land for a pipeline exporting gas abroad.

Meanwhile, national environmental advocacy groups, including the Sierra Club, warn that the project is advancing with limited federal oversight and goes against the Biden administration’s stated climate goals of phasing out fossil fuels.

The pipeline proposal recently received the blessing of the U.S. Department of State, and the state Railroad Commission — which regulates oil and gas and oversees pipeline safety in Texas — issued a permit, months before residents in Van Horn say they knew about the project.

Now many are pressing state and federal agencies to force the company to reroute the pipeline farther from town or kill the project altogether — even though other pipelines crossing from Texas into Mexico have been granted permits without the additional scrutiny advocates are calling for.

Because the Saguaro Connector would not cross into other U.S. states, federal regulators are only responsible for permitting a 1,000-foot section where the pipeline crosses the Texas-Mexico border and don’t have authority over its route through Texas. The Railroad Commission of Texas also lacks legal authority over the pipeline’s route.

But residents and environmentalists argue that because the pipeline would transport gas for export abroad, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which regulates natural gas pipeline construction, should review the full route and assess its likely contributions to climate change for years to come.